Scottie Wilson’s Walter Barnard & Son tweed cap in Tate Archive

Photo © Tate (Sam Day)

The cap is suspiciously pristine. Made from brown tweed by Walter Barnard & Son, the trademark headgear belonged to the artist Scottie Wilson. Born ‘Louis Freeman’ in Glasgow in 1889 to a family of Lithuanian Jews, he gained success in later life as the creator of highly technical, stylised and fantastical works in crayon, pen, ink and gouache, such as The Bowl of Life 1958–9 and The Tree of Life 1958–9 (both in Tate’s collection). Both Jean Dubuffet and Pablo Picasso were admirers. Following his death in 1972, he has been known principally as an ‘outsider artist’.

‘I’m listening to classical music one day – Mendelssohn – when all of a sudden I dipped the bulldog pen into a bottle of ink and started drawing’, Wilson told Mervyn Levy, who would write a monograph on Wilson’s life and work (and donate the artist’s cap to Tate Archive). Wilson was 43 and a failing shopkeeper in Canada at the time. George Melly received a slightly different account for his book and added ‘ex-newspaper boy, street-trader, soldier, deserter, lumberjack’ to the list of Wilson’s professions.

The ‘outsider art’ narrative is clear: self-taught, uninfluenced by other artists, idiosyncratic and obsessive. In Wilson’s work, stylised fish, flowers and birds populate landscapes arrayed about totem poles (Wilson spent 15 years in Canada), castles and fountains (possibly recalled from Glasgow’s public parks). A hostile family upbringing is signalled by the appearance of his brothers as sinister, bearded figures that Wilson called ‘Greedies’. He drew, he said, because it was quicker. By the time of his death he had produced, alongside the drawings, crayon and gouache works, designs for pottery and cards.

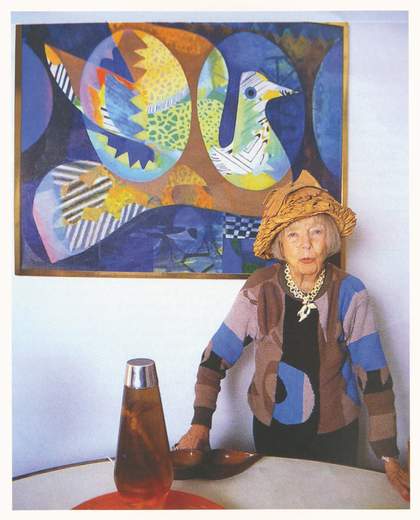

Scottie Wilson wearing his tweed cap while shopping at Sainsbury’s, 1964, photographed by Ida Kar

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Roger Cardinal coined the term ‘outsider art’ in 1972, the year of Wilson’s death from cancer. The parameters were derived from art brut, defined by Dubuffet as work ‘created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses’. Wilson fits the bill perfectly. Even more authentically, he was semi-literate, seems to have drunk too much and was socially awkward to boot.

Returning to Britain in 1945, Wilson exhibited alongside the likes of Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee, but, rejecting the commercial gallery system, he chose to try and sell his work on the street. One anecdote recalls him buying and assembling a shed to use as a gallery.

Eventually, however, Wilson was represented by the Belgian surrealist E.L.T. Mesens, who ran the London Gallery. Wilson lived modestly in Kilburn but was well off at his death. His work featured prominently in Cardinal’s Outsider Art show at the Hayward Gallery in 1979.

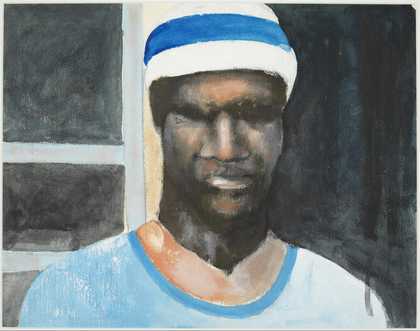

Scottie Wilson

The Bowl of Life (1958–9)

Tate

Then, the concept provided a haven for artists, and a way for the public to view work it might otherwise dismiss. But Scottie Wilson was still an ‘outsider artist’ in the eponymous Tate show of 2005–6. In 2021, the tag feels more like a trap than a lens, as if his work signals no more than oddity, a lack of professional training and some mental health issues.

In Wilson’s best work, his draughtsmanship, control of line and uninhibited sense of colour are put at the service of an intricate iconography that is as intriguing as it is confident and ambitious. Outside? Outside what? For me, Wilson’s work advocates a different ordering of the world. And a different Scottie Wilson hidden under the hat.

Scottie Wilson’s tweed cap was presented to Tate Archive by Mervyn Levy in 1990. To explore Tate’s digitised archive collections, visit tate.org.uk/art/ archive/collections.

Lawrence Norfolk’s latest novel is John Saturnall’s Feast, published by Bloomsbury