Hew Locke, photographed by Danny Cozens, 2020

ELENA CRIPPA Could you tell me about the inspiration behind your commission for the Duveen Galleries?

HEW LOCKE One of the driving forces behind this show was a Tate briefing for a press view in the run-up to Artist and Empire at Tate Britain in 2015, in which some of my work was included. The line to toe was laid out: that Henry Tate – of Tate & Lyle, whose art collection formed the basis of the first Tate gallery – made his money from sugar cubes, but had nothing to do with slavery, as it was after abolition. Bish bosh, move on, the oracle had spoken, and there was no blame or guilt at the gallery to do with sugar and its problematic history. And I kept thinking, this feels uncomfortable. It was a statement that I had difficulty with.

EC So much of your work is about addressing history and asking who owns it.

HL Exactly. What I’d heard was: ‘We own this type of history; we have the right to say this is how it is.’ And I thought, it’s more complicated and messier than that. You cannot just shirk that responsibility so easily.

EC Being here in your studio with work in progress for the commission, I recognise lots of images that you’ve worked with over a long period of time, but some new imagery too.

HL I’m mining my back catalogue for this show. Mining it and reworking it – presenting things differently. And making something complicated and messy make sense for the setting in which it will be shown.

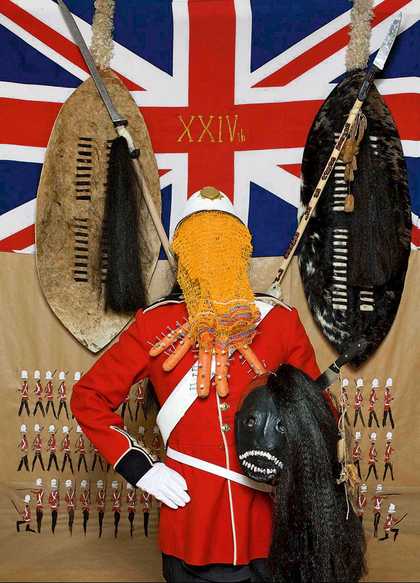

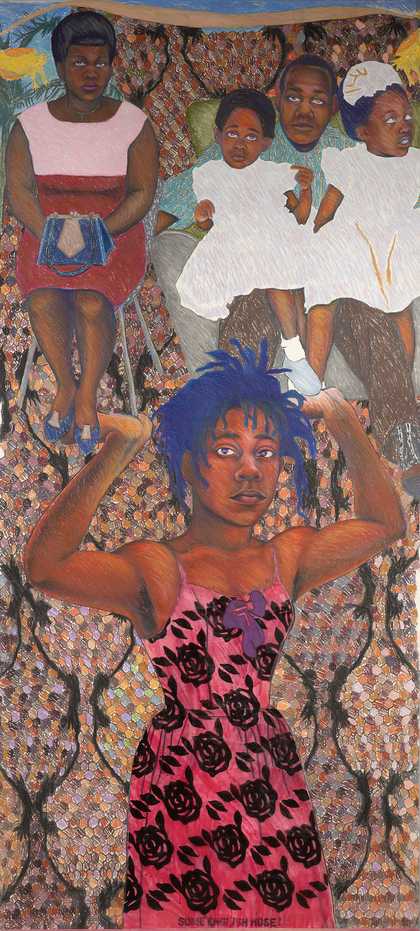

Work in progress ahead of Hew Locke’s Tate Britain Commission, photographed at the artist’s studio in London, November 2021

© Hew Locke. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. All photos © Tate (Matt Greenwood) 2021

EC You often use relatively inexpensive materials, such as cardboard and mass-produced plastic objects, and then subject them to incredibly labour-intensive processes. What drives that approach?

HL It’s important for me that you can see that everything has been hand-sewn. Pretty much a solid year of work has gone into this project, and the design was much more on top of that. But it also has to have this casualness about it, which belies the effort it has taken to produce it. There’s something about that which I like, instinctively.

I cannot completely see how everything will turn out. But when it’s done, I know it will make sense. And even if it doesn’t, that doesn’t matter. People want someone to talk about art and say, it’s clear, you know what this guy’s on about. But I’m interested in confusion and insecurity, because that’s a human condition as well.

EC You’ve mentioned Tate and its history, which can be daunting for an artist. How are you addressing it?

HL Yes, it’s tricky. I’m using some imagery which I’ve never used before, like the famous print of the Brooks slave ship from the late 18th century showing how people were packed into it. For me personally, it had become something that had been used a lot by other artists, to the point where I’d been sort of desensitised to it. The stories, the first-hand accounts, that’s a different thing. They still have the power to really mess with my head. But I’ve used the Brooks image as part of the new commission because of the space I’m showing it in – I think it’s important for it to be present at Tate because it makes links with the historical after-effects of the sugar business, almost drawing out of the walls of the building.

Work in progress ahead of Hew Locke’s Tate Britain Commission, photographed at the artist’s studio in London, November 2021

© Hew Locke. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. All photos © Tate (Matt Greenwood) 2021

EC As well as collective histories, so much of your work addresses your own personal history. You were born in Edinburgh in 1959 and you moved with your family to Guyana at the age of five, where you remained until you were 20, before coming to England to go to art school.

HL My parents were both artists and, growing up, I tried very hard not to be an artist. I wanted to be a his- torian or an architect. But when I was about 14 or so, in my art class run by the Guyanese painter Stanley Greaves, I started painting a hibiscus flower, and for the first time I felt, oh, so this is what this thing art is. I realised I had stopped copying the flower, and was instead creating it. That stayed with me, and I would eventually come to England to go to art school.

EC Did being of mixed heritage mean you felt you didn’t quite fit in either place?

HL Well, in Guyana I fitted in fine. Guyana is a mixed-up place. Also, I grew up in a network of white women who’d married Guyanese men and had mixed race kids, and they were naturally drawn to one another because they were in this unusual situation.

EC Is being British more complicated?

HL I find it tricky because there’s a pressure in a certain sense, because of the visibility of this commission, that I must represent a Black British point of view. And I think, well, what is that? This is a multi-layered piece of work, and I’m British, but I’m also Guyanese, so it’s complicated. I hold them both in me at the same time. I do feel there’s an unreasonable and unachievable expectation to represent something bigger than myself – a Black British perspective, or a Caribbean perspective.

Work in progress ahead of Hew Locke’s Tate Britain Commission, photographed at the artist’s studio in London, November 2021

© Hew Locke. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. All photos © Tate (Matt Greenwood) 2021

EC Did you grapple with these ideas after you moved to the UK?

HL There were very few non-white people at Falmouth School of Art, but I remember artists Eddie Chambers and Rasheed Araeen came down to talk. Within about two years I was writing a highly political thesis, which got me a First, actually. Because I come from Guyana, I come with a complex idea of identity and race. I grew up in a country which people think of as being Afro-Caribbean, but about two-thirds of the population of Guyana originate from India.

EC Representation, history, identity – none of those issues are simple...

HL Yes, exactly. I’m proposing a complex history. For example, an image I am re-using from a previous work is that of a Greek refugee share certificate from 1924, which is when Greece split from the Ottoman Empire and the country was having to seek money using Government-issued loans, backed by other European powers, to support their refugees. Now, a hundred years later, Greece is in a situation with refugees again but it’s very different. So, it’s about the vagaries of history, the spirals of history, things going out and coming back in again.

There are lots of messy nuances in history, so my commission is like a spider’s web, with one thing linking to another. You may think, this doesn’t link to that, but for me, even if it’s not necessarily literal, there’s a poetic link. You’re talking about a global situation and that’s even more relevant now because of climate change and how that connects us all.

Work in progress ahead of Hew Locke’s Tate Britain Commission, photographed at the artist’s studio in London, November 2021

© Hew Locke. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. All photos © Tate (Matt Greenwood) 2021

EC I think you’ve touched on something crucial in your work: the rippling of history, and the issue of time, which is not only linear.

HL Time is not linear and things linger. For instance, I’ve done a lot of work over the years that refers to wars of the 19th century, and you might think that those battles are done, that they’re history. But I once read a story at the National Army Museum by a British captain who was in a village in Helmand in 2002, during the most recent war in Afghanistan. They were trying to win hearts and minds, but the villagers were terrified that the soldiers were the Soviets back again, from the previous Soviet–Afghan War (1979–89). When the captain explained they were British, the villagers said, ‘Oh, you’re the ones who burnt down the bazaar.’ This captain panicked and asked his colleagues who had done this, but nobody knew. Eventually one guy said, ‘We did burn down the bazaar, but it was about a hundred years ago during the First Afghan War (1839–42)!’ This memory had lingered in popular consciousness. For us, some stories are dead and done. But for other people in other places, they’re not. They’re in the popular consciousness.

EC After Falmouth, you moved to London and eventually did an MA at the Royal College of Art. How did your experiences there influence your work?

HL My degree show included a large cardboard and papier-mâché boat, which people liked even though it didn’t fit with what was coming out of the Royal College of Art at all, particularly at that point in time. It was the height of the Young British Artists (YBA) thing, and I had a real problem with it. The ‘canon’ was very restricted, and the art world very London-centric. I was globally orientated – I was interested in what was coming out of Africa, Cuba, and Latin America... It was only after I left that I started to meet a whole bunch of international artists, especially at Gas- works studios, which felt like the unsung, unrecognised hub of an alternative international art scene. So many people, now internationally recognised, came through the doors and it was refreshing. But we felt that we were operating on a distant island – we didn’t seem to be visible. The world slowly changed and evolved. But it took time.

I remember my life drawing tutor sent me to a show of British art called The Hard-Won Image at Tate back in the early 1980s. It included Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon... It was an important, seminal show, but I hated it, because it was all these men, Englishmen, good artists, but the particular way it was presented – fetishising their ‘hard-won image’ – made me feel, well, there ain’t no room for me.

So that’s when I started to diverge. It came from a conscious effort to go against what was being given to me, presented as the dominant culture. I was trying to come up with something different, and now that has just become what I do.

EC But, of course, a dominant culture is not simply a given, it is also constructed.

HL Yes, exactly. Auerbach wasn’t born here. Freud wasn’t born here. And I suddenly saw these British artists differently. This was an adopted country for those guys, you know what I mean? It’s an adopted country for me too. The irony is, I was actually born here.

EC Journeying, departure, movement and migration seem to be a key part of your life and work.

HL Migration, movement of people from one place to another and what they bring with them, will continue to be a strong theme in my work, because it’s everything. When I was a kid in the 1960s, I went to Guyana by boat, and I returned to Britain by boat in the 1970s. Sitting here, I can still remember the smell of the cabins, the engines. Then, many years later, I went to the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton and realised that the boat that I had been on for so many weeks was the same one that brought people from Jamaica, post the Windrush generation. It was a surprise to see this boat ticket and think, oh God, I’ve done that walk. Once you’ve been part of that, migratory shifts are something you become very conscious of, particularly in a city like London.

EC This is another fantasy that has been constructed – that people are of a place and have always been of the place. In reality, there has always been constant movement between places.

HL Exactly. The boat I was on, the Montserrat, was bringing people to live here. On the way back it was taking people for holiday in Jamaica. That doesn’t figure in discussions around migration, immigration, emigration. What also doesn’t figure is the fact that people came here to study and then went back home. The story of my dad is that he came here to study and then returned home. He came back here again, but that going back home – which was a short but really a seminal part of his life – that gets left out. It’s almost like the Windrush arrived with all these people, and people just came out and stayed – as if it was a static kind of thing. That is not the case. That’s not how history works.

EC History is crucial to your work. And yet, it also has many imaginative layers.

HL That’s it. It’s about the historic and the imaginative in equal measure – and if visitors will feel that, well, that’s enough for me.

Tate Britain Commission: Hew Locke, Tate Britain, from 22 March 2022. Supported by the Tate Britain Commission: Hew Locke Supporters Circle.

Hew Locke is an artist based in London.

Elena Crippa is Senior Curator, Modern and Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain.