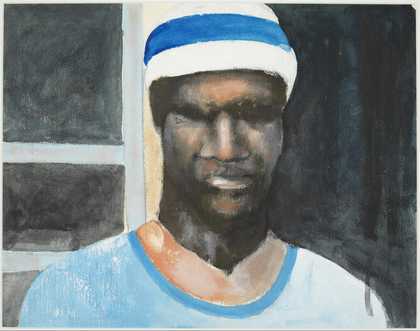

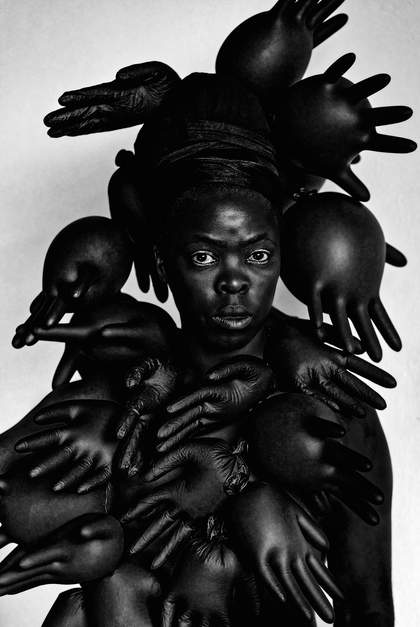

Liz Johnson Artur Time don’t run here 2020–1. © Liz Johnson Artur

YASUFUMI NAKAMORI When did you start thinking that you might want to become a photographer?

LIZ JOHNSON ARTUR I did my A Levels in Germany, and at that time I was quite without any direction. I was living with a friend, and one day his brother said, ‘Let’s go and take some photographs.’ I was never really bothered about photography at the time. But we took these pictures and my friend said, ‘If you want, we can go to the darkroom and process the film.’ I think that experience really hooked me on photography, because I realised: ‘Actually, I can take a picture and I can do everything else myself as well.’ And a few weeks later, I organised a darkroom in my bathroom.

In the beginning I was quite intimidated by everything, but there was a moment where I just knew I wanted to take some pictures, so you kind of push yourself in that direction. I went to New York, I took pictures, I tried. And from there I went back to Germany, and then I ended up coming to London. I didn’t really have a plan, but I thought: ‘Okay, maybe it’s a good stopover before I go back to New York.’ And that’s how I arrived in Elephant and Castle.

Liz Johnson Artur Time don’t run here 2020–1. © Liz Johnson Artur

YN What did the ‘suspended’ time of the two national lockdowns in the UK bring to you?

LJA I wasn’t at the receiving end of things when they started to fall apart. I had my family, my work, a home and most importantly, time. I was one of the lucky ones. I had access to a darkroom and some black and white film, and a lot of the mood – the strangeness of that time, the absence of people on the street – I took in by taking pictures and spending time in the darkroom. My pictures are very much about what I see, but what this time really brought out was a need to show in my work how I ‘feel’ about it.

YN Where does the title of the work come from, and why did you decide to print the photographs on pages from the braille edition of Iris Murdoch’s The Red and The Green (1965)?

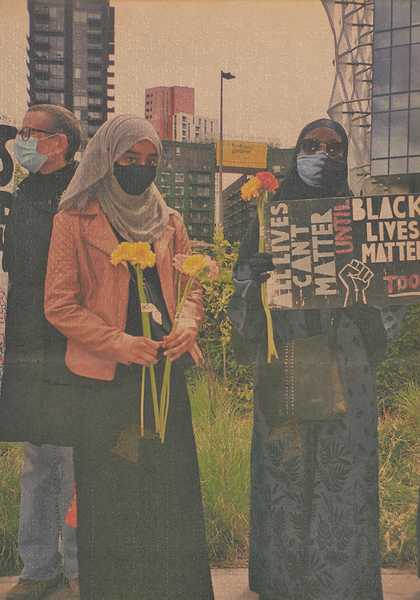

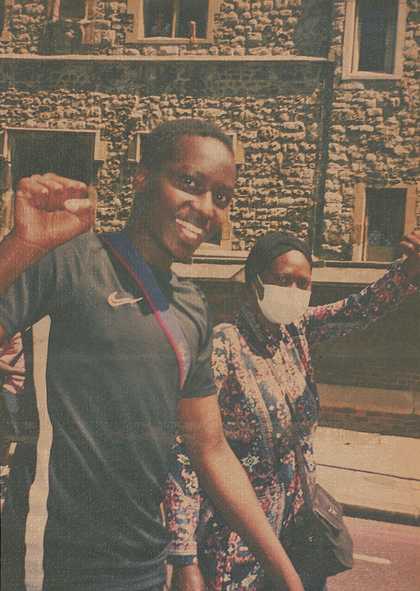

Liz Johnson Artur Time don’t run here 2020–1. © Liz Johnson Artur

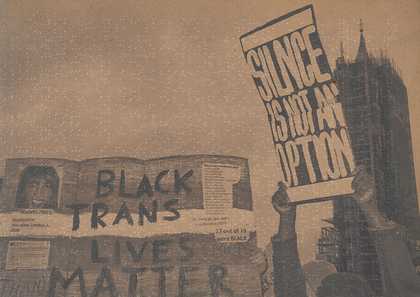

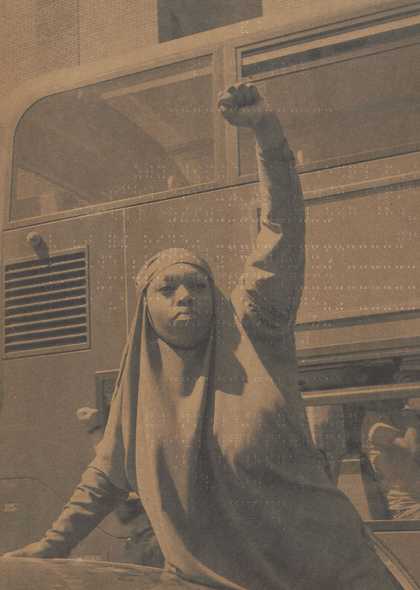

LJA I was locked down for almost three months in Brighton, seeing only my family. But when I heard about the first BLM march, I had to go to London. My daughter went with me – the majority of demonstrators were young people. When I was taking pictures I tried to look at faces, signs, places – not wanting to miss anything – and to preserve these moments, I decided to connect them with ‘time’. I can’t say what went through my head, but I knew that whatever pictures I took, I wanted to preserve them for the ‘test of time’. The title of my work comes from trying to find a way of saying ‘Time don’t run here – it’s up to you where you take it.’ I chose Iris Murdoch’s novel (in braille), because it represents time in a physical sense, having been printed in 1968, and because the words (which you can only read by touching the paper) deal with ‘British History’.

YN Speaking of books, can we talk about the importance of photobooks and photozines in your practice? In these publications, each picture is experienced as part of a time-based spatial experience of flipping through pages.

Liz Johnson Artur Time don’t run here 2020–1. © Liz Johnson Artur

LJA A photobook or photozine is always part of how I’m trying to engage – this thing of seeing it as a whole without having this sort of direction. You know, like a photograph hasn’t got a title, and one reason I didn’t want a title was because I didn’t want any direction. You can look at a photobook picture-by-picture or you can go back and forth, and I think that’s also closest to how I keep my work. I don’t write down what day I took a particular photograph, or what year. I remember each picture in terms of the moment, how I got there. I know the year and I know the place, I just don’t know the names of the people in them. That would have been a whole different journey to get every name. But in order to connect with someone, you don’t need to know their name. You can sometimes just spend two seconds exchanging something, and you both go away richer than before. For me it’s never been a thing of wanting to get a picture because I can get away with it. Instead, sometimes it’s the result of a very direct engagement with someone, and most of the time what I try to show is interest.

Liz Johnson Artur Time don’t run here 2020–1. All © Liz Johnson Artur

YN How do you show interest?

LJA Now, after doing it for 30 years, I can tell you it’s just by going up to someone and saying, ‘I want your picture.’ But that’s not a journey that I’ve started – it’s a process and that’s why my work exists on these levels, through engaging. Engaging by taking photographs, by being in situations where I have to have the courage to go up to someone and ask. It’s a very humbling experience to go up to a stranger, but by now I’ve learned that honesty is the best way, so first of all I tell them why I’m interested. You know, a lot of the time my interest comes not so much through someone’s style but how people carry themselves. And people can say yes or no. And sometimes they say yes, and I always think, ‘Wow!’ Really, to this day I’m amazed when people say yes.

YN Lastly, the theme that connects this issue with the other three Tate Photography publications is ‘community and solidarity’. What does that term mean to you? And what or who is your community?

LJA When I take pictures, I experience a lot of community and solidarity. That’s an everyday thing for me, because I always look out for it.

Liz Johnson Artur, edited by Yasufumi Nakamori, will be published in May as part of Tate Publishing’s new Photography Series. The book is one of four titles on the theme of community and solidarity. The other photographers in the series are Sheba Chhachhi, Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen and Sabelo Mlangeni.

Liz Johnson Artur is a photographer based in London.

Yasufumi Nakamori is Senior Curator, International Art (Photography), Tate.