Editorial

‘Painting from nature,’ Paul Cezanne once said, ‘is not copying the object, it is realising one’s sensations.’ Many of us think we know how to engage with art in terms of what we can see, but how might we experience art through our other senses? This is a question that inspires Tate curator Marcus Dickey-Horley, who, with his team, has spent the past 15 years developing and delivering touch tours for visitors who are blind or partially sighted. At Tate Britain this autumn, you will find them guiding groups inside and outside the galleries, stopping to handle and discuss artworks such as Henry Moore’s King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957, Hew Locke’s The Procession 2022 and Frederic Leighton’s An Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877 – the scales of the snake cool to the touch and the strain in the young man’s arms immediately recognisable beneath one’s fingertips.

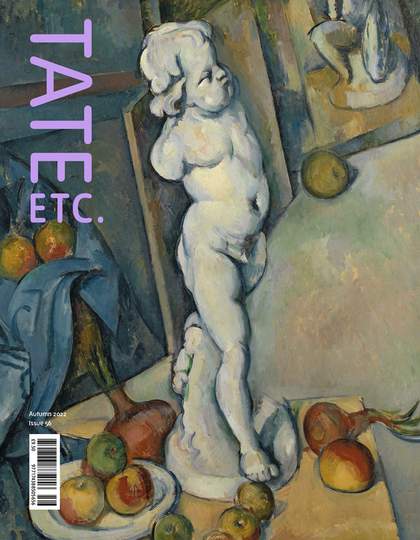

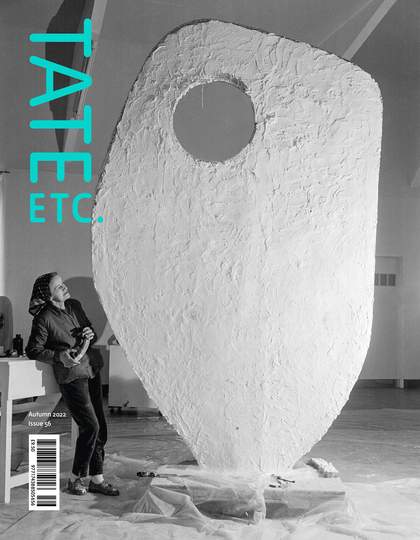

We have taken touch as a connecting theme for this issue, and in the following pages are the traces of many artists’ hands at work. We visit the studio of sculptor Maria Bartuszová, who created delicate plaster forms inspired by nature, as well as tactile ‘assembly kits’ for blind and partially sighted children. Elsewhere, Cecilia Vicuña talks to us about the quipu, the ancient Andean system of knot-tying that will form the basis for her Turbine Hall commission, and artist duo Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings teach us about the hands-on process of fresco painting. In a special feature on Cezanne, celebrating a major exhibition

at Tate Modern, artists from Cezanne’s time and from our own describe the many ways in which his paintings have left a mark. As Cezanne said, ‘An art which isn’t based on feeling isn’t an art at all.’

Tate has a large and growing programme of activities and resources to ensure all visitors can access and engage with the national collection. ‘Everybody,’ Marcus says, ‘should feel that Tate is open for all.’ With this issue of Tate Etc., we are following suit: you will now be able to listen to our articles online at tate.org.uk/tate-etc.

We hope you enjoy it.

Tate Etc.