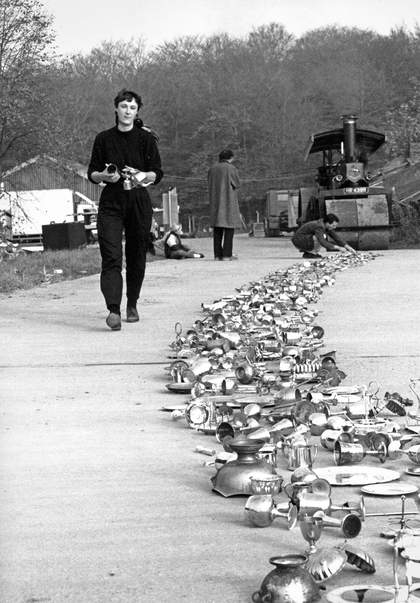

Cornelia Parker at the White Cliffs of Dover, 1999

Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London. Photo: Jeff McMillan

Listen to this article

I studied Fine Art at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in the 1970s. Being a country girl, I found the city pretty gritty, full of urban decay and politically charged: I remember a lot of anti-Nazi protests in particular. Wolverhampton was one of the only colleges in the country that had spaces left available in clearing, so it chose me rather than me choosing it.

I was practising to be a painter, tussling with representation by trying to paint the physicality of light coming in through a window. I found I liked the reality of light itself much more than my crude depictions of it. I would escape college to nearby derelict houses and spend many hours there finding other ways to capture light, using torn-up wallpaper and a staple gun. Some of my interventions took on three dimensions for the first time. Little did I know then that I was becoming a sculptor – and, even more radically, an installation artist. Later in my career, I had a eureka moment when I realised that the very first art forms – cave and body paintings – were, in fact, site-specific installations.

Another experience that led to my becoming a sculptor occurred on a field trip to the artist David Nash’s studio in Wales. A few of us lucky students got to stay there for a week and observe his practice first-hand. David made interventions in the landscape, planting trees in circles and fletching them (cutting them partially and bending them over) so that they became intertwined, forming a kind of espalier. Some of his works take years to be realised; some are planned beyond even his own lifetime.

Blaenau Ffestiniog, the town where Nash still lives and works, was once a slate-mining centre and is surrounded by grey shale slag heaps. Being Wales, the weather was atrocious during our visit, and trying to draw in the wind and rain was challenging to say the least. But it was while I was doggedly trying to capture this grey landscape, which was alien to me, that I had another of my epiphanies. I had a jar of powdered graphite that I was rubbing into my paper to give it a grey patina when some large raindrops descended, splattering onto my drawing. Then the wind picked up and a gust blew the powder across my paper, leaving these beautiful marks where the rain had fallen. Nature itself was making the work. This was a similar realisation to the one I had come to in the derelict houses, where I had allowed (real) light to be part of the work rather than struggling to depict it.

I devoted the rest of my degree to making sculpture. At last, I had found something that was second nature, informed by a childhood working with my hands on my family’s smallholding. Material and process have their own history; all they need is corralling.

Cornelia Parker, Tate Britain, until 16 October. Curated by Andrea Schlieker, Director of Exhibitions and Displays, with Nathan Ladd, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art, Tate Britain. Supported by the Cornelia Parker Exhibition Supporters Circle, with additional support from Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members.

Cornelia Parker is an artist who lives and works in London.

Audio narration by Wesley Nzinga.