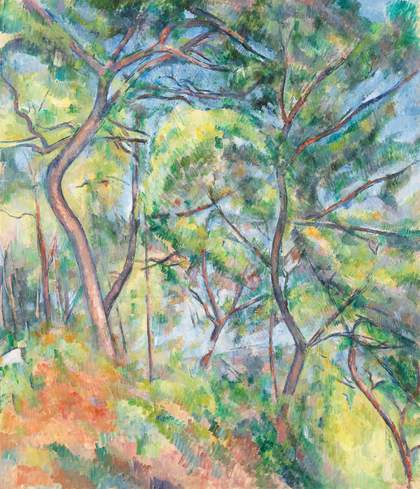

Paul Cezanne

The Sea at L’Estaque behind Trees 1878–9

Oil paint on canvas

73 × 92cm

Listen to this article

Letter from Aix-en-Provence, July 23, 1990

I’m in the countryside of Aix, ... a dry country with an unforgiving light. That’s why, I think, Cezanne stayed here. Because the light would allow him to go all the way ...

Cezanne is ravaged by his instinct for observation. His gaze eaten by the sun, his eagle eyes fix Madame Cezanne on paintings in which she seems to be dozing with boredom, knowing that she would never be the Sainte-Victoire. Two women dominate Cezanne’s life: Madame Cezanne, and the mountain whose name is a woman’s ...

In the penumbra of my thought a question arises: why does the feminine dominate the world of Cezanne, and of Pablo Picasso?

For Cezanne, nothing is less evident. I’ve just seen in his workshop some of the ordinary objects, placed one next to the other, which he used in his paintings: a kitchen table, pots and pans, ceramic ware, morose things that his genius, on the canvas, transfigured. I’m thinking about the flower vases, the apples, and his mountain. ... I tell myself: art is the search for the feminine, and in turn, art feminises the world. Hence its indispensable value to society and its powers of subversion.

Email, December 8, 2020

Last night, thinking of Cezanne, it became clear to me that a painting by him is mainly an organised chaos. Look at his tablecloths: they are verticals put on his tables; his apples on a table, though intensely lit, lack shadows and stare at us; in real life, his little ceramics would roll down on the floor and break, but the organisation ends up making sense. And, going on, I looked at his watercolours, in my memory, and realised that his touches, his strokes of colour, have a strangeness due to the fact that they are not three-dimensional but are pure vibrations, immaterial statements of matter making, aggregating in ghostlike mountains, the whole endeavour a pursuit of that immateriality which led the nineteenth century to the disintegration of matter through the atom bomb.

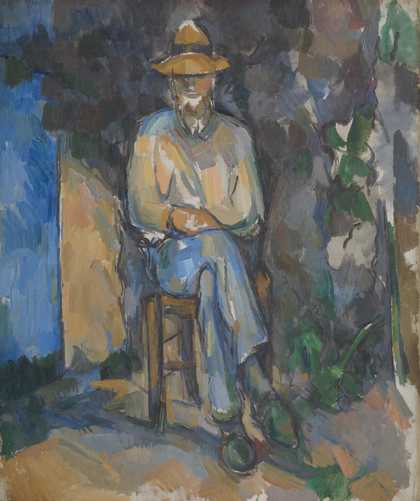

Paul Cezanne

The Gardener Vallier (c.1906)

Tate

Email, June 19, 2020

Of all my experiences of Cezanne’s works, the most haunting have been his portraits of the gardener Val- lier. Of course, the Mont Sainte-Victoire paintings and watercolours have occupied my mind for years. But the epiphany came with the gardener’s portraits.

This is a simple man, maybe the closest to Cezanne. He is sitting on a small wall, or on a chair. He has a thin face and penetrating eyes, and is sunk in a meditation, probably in a lifetime of meditations. And the nobility it entails. It could be a self-portrait of Cezanne, unwillingly emerging from the paintings. The whole body is guessed. In a photograph of his I noticed his long legs with angular bones, the type of legs that I suppose Arthur Rimbaud had too, in the same end-of-a-century time when the poet in his restlessness used to walk on foot from northern France to Germany, while Cezanne was hurrying to the spot from which he would, again and again, try to catch the fluidity of the mountain’s image. The gardener Vallier’s portrait is Cezanne’s ultimate ‘mountain,’ his Ecce homo, his real testament. The gardener is sitting cross-legged, looking from his bench at the master’s studio, lost in his thoughts. And Cezanne, watching him, is overwhelmed. No philosopher’s portrait has ever reached the evocative power of this one.

Etel Adnan (1925–2021) was an artist who lived in Lebanon, Syria, France and the United States.

This piece was first published in Cezanne by The Art Institute of Chicago and Tate Publishing. Letter from Aix-en-Provence was first published in Etel Adnan’s Of Cities and Women (Letters to Fawwaz).

Audio narration by Wesley Nzinga.