Sarah Lucas in her studio in Framlingham, Suffolk, photographed by Katie Morrison, June 2023

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Katie Morrison

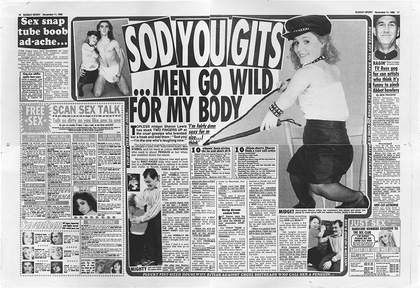

An especially early work by Sarah Lucas, Sod you Gits 1990, reproduces a spread from the British newspaper the Sunday Sport, and the headline that leaps out from the resulting large-scale collage feels now, with the benefit of hindsight, like an elegant announcement of her modus operandi as an artist: ‘SOD YOU GITS’, it snarls, next to an image of a smiling, diminutive woman with a whip, ‘MEN GO WILD FOR MY BODY!’

A recent graduate from Goldsmiths University at the time, Lucas had been reading extensively about misogyny in pornography and media, and while in theory she disdained this kind of tabloid coverage for its sexism and sleaze, she also had to admit that her relationship with it was more complicated than some schools of feminism tended to allow for. Yes, she identified with the sexualised female subject; she also identified with the implied male viewer, hardly a stranger to unruly, animal desire herself. By blowing it up and re-contextualising it in the space of a gallery, and by doing so as a female artist, Lucas turned a trashy piece of journalism about an S&M kissogram into a canny exploration of the ethical and intellectual contradictions inherent in being fuckable – or fucking – as a woman. Sod you Gits, with its headline that is both a rough challenge and a come-on, becomes an aggressive statement about wanting power, and also wanting to be wanted; about occupying a feminine body that is seen as being both too much and too little; and above all else, wanting to say ‘fuck off’ and ‘fuck me’ in the same breath, without feeling like a self-betraying hypocrite. The work explodes like a shot out of a (humorously phallic) starting gun, announcing the arrival of a documentarian of female sexual life unlike any other in art history.

Sarah Lucas

Sod you Gits 1990

Photocopy on paper

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Via its elevation to the status of an artwork, Sod you Gits is, per Lucas, ‘converted from an offer of sexual service into a castration image’. The gossamer-fine line between a provocative sexual statement and a ballsy sexual threat is permeable in her work, and that permeability results in an aesthetic sensibility that is bracing and quite often very funny. Arguably her most famous early sculpture, Au Naturel 1994, depicts a ‘couple’ on a filthy mattress, with the woman’s body represented by two melons and a bucket, and the man’s reduced to two oranges and a penile cucumber. The dissonance between the elegant title (with which Lucas seems to say, pardon my French) and the earthy assemblage of objects is itself a joke, implying that the piece is both an entry into a centuries-long canon of traditional nudes and also a more realistic, or ‘natural’, vision of romance and Eros than the ones we are more used to seeing in this context.

Because it reduces both the male and female bodies to their most essential – or at least to their most pleasurable – parts, Au Naturel is less about misogyny than it is about the way that arousal strips us down to the simplest, unloveliest versions of ourselves. It’s equal-opportunity objectification; it’s antagonistic, it’s amusing, and, above all else, it’s fun – the way sex itself is, when treated like a sport and not merely an ideological battleground.

Sarah Lucas

Au Naturel 1994

Mattress, melons, oranges, cucumber and water bucket

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Lucas is political, but she allows politics and pleasure to coexist, just as she allows humour and cruelty to brush up against each other and, in doing so, enhance each other’s potency, like perversely complementary flavours in a Michelin-starred dish that happens to be made entirely out of ingredients that look a bit like breasts or cocks.

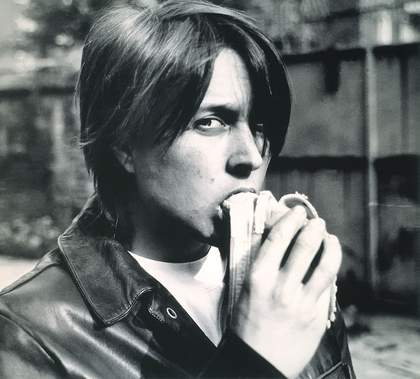

Lucas is also that rarest of things for a successful artist – cool – and this loucheness is integral to her work, especially when she is literally appearing in it. Her self-portraiture and her publicity photographs, which, taken together, document the changing of her face over a period of more than 30 years, suggest a solidity and continuity of personal style that is almost logo-like: the same androgynous bob; the same rockstar-like posture; the same omnipresent cigarette.

Sarah Lucas

Eating a Banana 1990

Digital print on paper

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

If a number of these images have technically been taken by her lovers, they remain self-portraits because their true medium is Sarah Lucas’s Sarah-Lucas-ness, her way of staring down a camera as if she has not yet decided whether to fight it or fuck it. Think, for instance, of 1990’s Eating a Banana; as with Sod you Gits, it might easily be described as ‘an offer of sexual service’ being transmogrified ‘into a castration image’, since it is very hard to tell whether the banana in question is being blown or bitten in half, and her eyes seem to be daring us to guess. (In 2018’s series of Red Sky images, which depict the artist smoking in a hazy, laggy, cinematic style, she still takes a frame to break the fourth wall. Even when abstracting herself, Lucas makes sure we are certain who’s the boss.)

Sarah Lucas

Red Sky Gha 2018

C-print on paper

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Julian Simmons

A common mistake made when discussing her oeuvre is the contextualisation of her practice – and indeed her image – relative only to men or to the masculine, so that she ends up being painted as a tomboy or a ‘ladette’, making work that is transgressive by dint of her being a woman acting like ‘one of the boys’. In fact, she explicitly demonstrates that there is nothing inherently macho about liking filthy jokes, or getting pissed, or wanting to have casual sex, or appearing in self-portraiture with a bare face and a leather jacket. Lucas has always both looked and acted like a girl; it has merely taken us three decades to catch up to her conception of the feminine – one that can encompass lingerie and lager, being a bit of a scary misandrist and dick-crazed.

There may be no better demonstration of this particular brand of confrontationally casual femininity than in the pose that recurs in a number of her pieces, from 1996’s Self-Portrait with Fried Eggs to numerous sculptures that depict the female figure: a kind of spread-legged loll that somehow manages to be both laid-back and assertively impertinent, ‘manspreading’ with the ‘man’ snipped cleanly off. In 2015’s Michele, a naked cast taken from the waist down of one of Lucas’s friends, the knees are spread in a style that might suggest a gynaecological examination, were it not for the cigarette that juts rakishly out of the vagina, as if it were hanging from the lips of Marlon Brando or James Dean. (Rarely has a vulva looked more like it might be in possession of a motorcycle.)

Sarah Lucas

Self Portrait with Fried Eggs (1996)

Tate

Sarah Lucas

Michele 2015

Plaster, cigarette and desk

Installation view in the British Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

HONEY PIE 2020, a naked female figure made from tights and wire wool, wears cherry-red stockings and the kind of glossy platform boots typically associated with sex work or stripping, and her legs are similarly akimbo. SLAG 2022, a work whose title puts the ‘brutal’ in ‘brutalism’, casts another of Lucas’s sprawling women in chill, immovable concrete, making her – in a double entendre – perpetually hard. Truthfully, more than aping a male tendency to let it all hang out, these poses call to mind a tongue-in-cheek alembic of Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World) 1866 and the iconic Sharon Stone interrogation scene from 1992’s Basic Instinct – a celebration of the cunt that doubles as intimidation, both acknowledging it as a source of life and pleasure, and treating it as a weapon to be flashed in an ongoing fight between the (cis)sexes.

Bringing back that motif by repurposing an older photograph, Lucas made the sculptural-work-cum-installation This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven for her New Museum retrospective in 2018. The resulting piece is a sexy, bombastic distillation of her ongoing fixations on a scale that makes them hard to misinterpret. In the foreground, a 2003 Jaguar X-Type sits cut in half, the back end burnt out and the front collaged with cigarettes; on the wall, as a mural, a colossal portrait of the artist as a younger woman looms over the crash, her gaze locked into the lens. The car is split at the nexus of Lucas’s spread legs, and above each of the two pieces she appears to rest a solid workman’s boot. Yes, the car is a classically male fixation, and supposedly a penis substitute; yes, in her splitting of it there is another implied reference to castration; yes, the mass of cigarettes must be a play on the dual meanings – for a British person – of the word ‘fag’, riffing on the stupid, homophobic hypermasculinity that often surrounds the collecting and restoration of motor vehicles.

Sarah Lucas

HONEY PIE 2020

Tights, wire, wool, shoes, acrylic paint, vinyl and metal chair

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

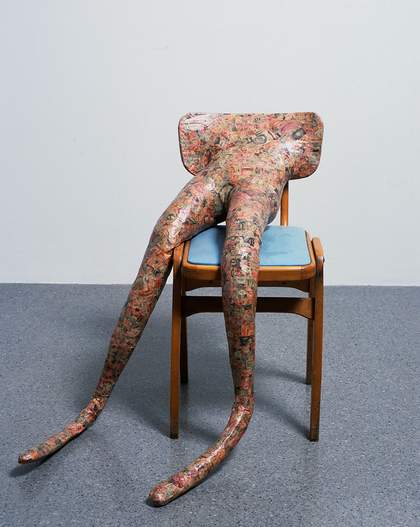

Sarah Lucas

Hysterical Attack (Mouths) 1999

Chair, collage and papier mache

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Robert Glowacki

There is something else, here, too, though – something that reminds me of the moment in David Cronenberg’s 1996 adaptation of J.G.Ballard’s novel Crash, when Dr Vaughan, a sexually motivated auto-accident enthusiast, says that ‘the car crash is a fertilising rather than a destructive event – a liberation of sexual energy’. During the year in which that film was released, Lucas claims to have been fixated on Sigmund Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), and especially on the way that it addresses the interplay between the sex and death drives. I am certain she saw Crash; her use of junked cars never quite feels entirely fatalistic – or not only fatalistic.

It would be all too easy to interpret a crashed car as a gag about ending up on the scrapheap when it’s being deployed by a female artist of a certain age. What if, instead, we read it as a statement about never slowing down, even when slowing down might be a safer bet – about the thrill of risk and speed, literalising those intermingling Freudian drives? If Sod you Gits was a bullet from a starting gun, here Lucas shows us something more like the end of the race: a smash that is not frightening, but libidinous, a climax of both pleasure and violence that underscores the artist’s breakneck progression through life, through work, through womanhood, and through sex.

Sarah Lucas

This Jaguar's Going to Heaven 2018

Car, cigarettes and glue

Installation view at the New Museum, New York

© Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Julian Simmons

Staring down three decades of velocity, Lucas barely blinks, although in the outsized photograph that appears in This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven, her eyes are half-lidded as if she is a gunslinger or a rally driver squinting into the horizon. When the late New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl reviewed that New Museum retrospective, he characterised Lucas as ‘scrumptiously naughty’, and his observation might have seemed a little sexist if it hadn’t also been entirely accurate. What could be naughtier than the impulse to blend dark, sophisticated adult sexuality with a childlike sense of play? And what is more delicious than a boundary being gleefully transgressed? A car wreck, after all, can be a sign of something tragic, but it can also be evidence of an ecstatic joyride.

Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas, Tate Britain, 28 September 2023 – 14 January 2024. Curated by Dominique Heyse-Moore, Senior Curator, Contemporary British Art and Amy Emmerson Martin, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain.

Sarah Lucas is supported by Burberry. With additional support from the Sarah Lucas Exhibition Supporters Circle, The Sarah Lucas Fried Egg Breakfast Club, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons.

Philippa Snow is a critic and essayist based in Norwich. Her first book, Which as You Know Means Violence, is published by Repeater Books.