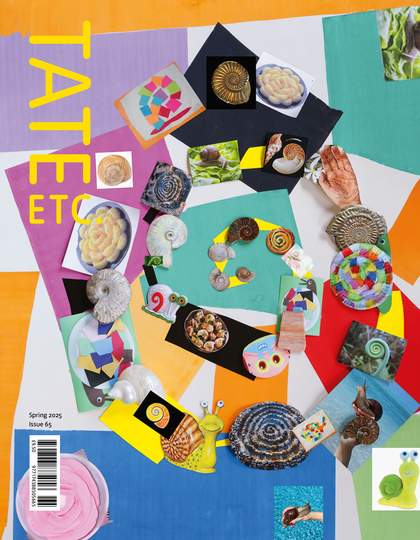

Mitra Tabrizian

Double Edge, from the series The Blues 1988–9

© Mitra Tabrizian. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

I made The Blues 1988–9 in collaboration with Andy Golding, a friend and fellow student, while I was studying under Victor Burgin at the Polytechnic of Central London. I had read Burgin’s book Thinking Photography (1982), which inspired me to take his course. Alongside the history of photography, we studied various critical theories that problematised the specificity of the medium – images can’t be understood in isolation.

Following two other student projects – College of Fashion 1987, in which I reworked documentary photography to critique the representation of women, and Correct Distance 1987–8, using the visual tropes of Hollywood film noir to explore the enigmatic figure of the femme fatale– I wanted to extend the critique of ‘otherness’ to address race and representation.

At that time, the dominant strategy was to create positive images to counter negative historical depictions of Black people. But, inspired by postcolonial theorists like Homi K. Bhabha and Stuart Hall, I saw the possibility of a different approach, one that deviated from the binary positions of Black and white, and questioned their absolute definitions.

Bhabha, in his essay ‘The Other Question’ (1983), writes: ‘The stereotype is not a simplification because it is a false representation of a given reality. It is a simplification because it is an arrested, fixated form of representation … The legends, stories, histories and anecdotes of a colonial culture offer the subject a primordial Either/Or.’ Either Black people represent a ‘negative difference’ – they are subservient or criminal, for example – or they are fetishised in a way that disavows that ‘negative difference’, through traits like beauty, athleticism or musical talent. Either way, the problem lies in the initial assumption of ‘negative difference’ and the fixation of the subject in the realm of fantasy and representation.

Hall, in his article ‘The Whites of Their Eyes’ (1981), distinguishes between ‘overt’ and ‘inferential’ racism. By overt racism he means those modes of argument and representation that openly circulate and popularise racist policies and ideas. Of ‘inferential’ racism, Hall cites TV programmes about race relations that conclude that if the ‘extremists’ on both sides were to drop their dogma, ‘normal’ people of all races could live in harmony. ‘However, these programmes operate on the unrecognised premise that Blacks are the source of the problem, assuming a pre-existing “natural” identity considered inferior, but now to be reconsidered on humanitarian grounds’, Hall writes.

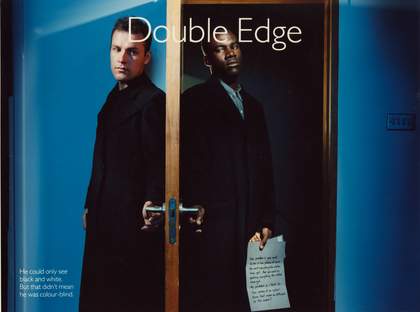

Mitra Tabrizian

Persecution, from the series The Blues 1988–9

© Mitra Tabrizian. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

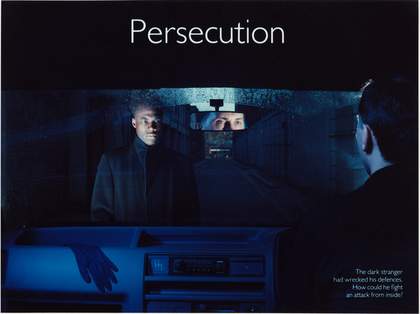

Mitra Tabrizian

Lost Frontier, from the series The Blues 1988–9

© Mitra Tabrizian. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

The title, The Blues, is used here as a metaphor for the Black voice – a voice of resistance. It consists of three triptychs, which use the codes of movie posters to construct, in each ‘untold story’, a critical moment in the confrontation between Black and white. What the Black man is confronting is the status of ‘whiteness’.

The blue colour is also an integral part of the mise-en-scène of most crime movies. No matter the position – whether under police interrogation, in prison, in a low-paid job or as an ‘invader’ – the Black man questions the white man’s identity. Yet, back then, the Black voice was still most often a Black man’s voice. So the work starts with a depiction of a confrontation between men, and ends with an encounter between a Black woman and a Black man.

I was pleased when Homi K. Bhabha agreed to write the texts for these images, which was a difficult task as they had to allude to the complexity of the issues expressed without being didactic. His words also take the narrative elsewhere, complicating it further.

When the series was first shown, it was criticised for being opaque: ‘Who are the goodies? Who are the baddies?’ Some people even questioned how, as an Iranian, I could address the Black experience. It wasn’t until Stuart Hall wrote about it that opinions shifted.

Three works from The Blues are included in The 80s: Photographing Britain, at Tate Britain until 5 May.

Mitra Tabrizian is an Iranian-British artist who lives and works in London.

Supported by Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Curated by Yasufumi Nakamori, former Senior Curator of International Art (Photography), Tate Modern, Helen Little, Curator, British Art, Tate Britain and Jasmine Chohan, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain with additional curatorial support from Bilal Akkouche, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, Sade Sarumi, Curatorial Assistant, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain and Bethany Husband, Exhibitions Assistant, Tate Britain.