Mark Wallinger

Half-Brother (Exit to Nowhere – Machiavellian) 1994– 5

© Mark Wallinger

It is a warm Friday in August 2024 and Mark Wallinger is at the finishing post at Epsom Downs Racecourse, puffing on an e-cig and waiting for the horses to come into view. We are looking up towards Tattenham Corner where Emily Davison stepped onto the track and was knocked down by the King’s horse in 1913 – and where, 80 years later, Wallinger was photographed in his racing colours and red lippy, in homage to the martyred suffragette.

The racecourse is a vibrant stage for social and political drama, and it has been a febrile summer. Only six weeks have passed since Labour came in first past the post, following an election that many Tories had backed themselves to lose. A month ago, the England men’s football team lost another major final to superior European opposition, and today, as the horses come thundering past, the dust has barely settled after far-right riots targeting migrant communities swept across the country.

We turn to the finish line. The race is too close to call, except for Okami, an Irish thoroughbred produced by a mare called Brexitmeansbrexit. ‘Good name, that’, someone nearby observes, unbothered by the fact her offspring has just finished in last place. The irony is lost on no-one, least of all Wallinger, whose work probes fictions of Britishness with a sharp eye for their contradictions and absurdities.

In 2007, he won the Turner Prize for State Britain, a reconstruction of campaigner Brian Haw’s decade-long protest camp in Parliament Square against the Iraq War. But it was in the work for which he received his previous nomination in 1995 that Wallinger’s fascination with the class stratifications, migrant histories and Hogarthian pageantry of the racetrack first came to the fore.

Recalling the races that have measured out his life, the artist is evidently happier talking about horses than he is talking about himself. He consults the day’s race card and explains that nearly 95 per cent of all thoroughbreds are descended from the Darley Arabian, a stallion imported from Aleppo, Syria in 1704. ‘So, if you want to talk about good breeding...’ he trails off, letting the implications around class and national identity speak for themselves. Wallinger’s work, likewise, doesn’t labour this point. He is an arch observer, rather than a polemicist, and avoids sweeping statements in favour of colourful stories: from run-ins with royalty to revelatory epiphanies in dimly lit stables.

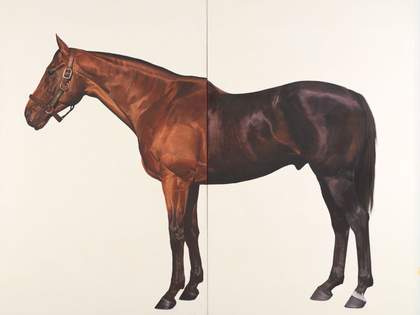

In his series of four Half-Brother 1994– 5 paintings – one of which was included in that initial Turner Prize show and now hangs at Tate Britain beside works by George Stubbs, the famed 18th-century painter of horses – his meaning is both forth-coming and oblique. Ostensibly, Half-Brother (Exit to Nowhere – Machiavellian) is a riff on equine genealogy, with both front and back ends of this hybrid racehorse descended from Eclipse, a stallion once painted by Stubbs and related in turn to the Darley Arabian. The plain background nods to Stubbs’s famous life-size painting of Whistlejacket c.1762 and the Jockey Club’s official record of thoroughbred stallions on which his paintings are based.

‘Wallinger brings the ineffable passions of the races into contact with what he perceives as artworld snobbery towards sport in general’

‘There were two dares for me,’ Wallinger explains. ‘One was to paint a horse after Stubbs, and the other was to enter the same stream, but so many generations down the line.’ Painted on two canvases that join, not quite perfectly, in the middle, the work also hints at the pantomime horse (of Wallinger’s 1993 work Behind You!, also in Tate’s collection) and the chimeras created in the childhood game, Consequences.

Stand under Half-Brother in person, though, and you begin to feel something else: a celebration of Wallinger’s genuine love for the anatomy of great horses, painted with such lustre that you sense something of the animal’s spirit in the room. Half-Brother makes Stubbs’s horses beside it look like toy miniatures, and in doing so approaches the core of the artist’s fascination with the animal. ‘It’s very hard to explain,’ he says. ‘There’s something about the thrill of seeing a truly great horse, the acceleration and the courage.’ He pauses. ‘A lot of it is beyond my understanding, which I think is probably part of the appeal.’

It is here that Wallinger engages in another dare – to bring the ineffable passions of the races into contact with what he perceives as art-world snobbery towards sport in general. Typically, Wallinger resists the either/or. He jokes that he may be one of just a few artists to have hit a hole in one on a golf course. His wider point is to challenge the notion of the incompatibility of raw emotion and high concept, as well as the value systems that mirror class systems, entrench hierarchies and sow division. As Half-Brother succinctly shows, a horse can be two things at the same time.

With no winnings to collect, we head back to the Queen Elizabeth II stand for chicken schnitzel and Spanish lager. ‘They’re on a bit of an art jag at the moment,’ he says of a recent trend for naming horses after famous artists. Auguste Rodin, Caravaggio, Diego Velázquez. I suggest he’s just waiting for a horse to be called Mark Wallinger.

There almost was. In 1994, Wallinger formed a syndicate and bought a race-horse. He had briefly toyed with naming it after himself before deciding on A Real Work of Art. This chestnut filly was to be a living readymade, all muscle and desire, poised to infiltrate every betting shop in the country with a Trojan mythology of its own.

It didn’t quite go to plan. A Real Work of Art lined up for her first race in September 1994, injured herself coming out of the stalls and finished in last place. ‘Thankfully, she only needed some box rest to recover and went on to win a race at Riem in Germany the following year,’ he reflects. It was a high-stakes collision of representation and reality in the shins of a thoroughbred racehorse, and although he might not have seen it at the time, A Real Work of Art said more in defeat than she ever would have in victory. Life is random, sometimes cruel, and perhaps, at the end of the day, there is nothing more British than an appreciation for glorious failure.

In his catalogue essay for the artist’s exhibition held at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery and the Serpentine Gallery, London in 1995, critic Jon Thompson wrote that Wallinger had ‘wanted to anaesthetise the spectral voice of chauvinistic nationalism’ while interrogating ‘the social and political terrain which feeds it’. Thirty years on, these concerns are more pressing than ever – even if it feels increasingly as if that horse has already bolted.

Half-Brother (Exit to Nowhere – Machiavellian) was included in the display Stubbs and Wallinger: The Horse in Art at Tate Britain. A new limited-edition print by Mark Wallinger, The White Horse 2007/2024, is available to buy at shop.tate.org.uk/editions.

Anton Spice is a writer and editor who lives in London.