Bridget Riley with Concerto 1 2024 in her East London studio. Photographed by Seraphina Neville for Tate Etc., April 2025

© Bridget Riley 2025. All rights reserved. Photo © Tate (Seraphina Neville)

Since the early years of the 1960s Bridget Riley has created a body of work – comprising paintings, drawings, prints and studies – that explores the perceptual experience of looking and seeing with visceral intensity.

For the viewer first encountering a work by Riley, a first glance is immediately held by the emergence of seemingly autonomous rhythms and movement within the work itself. A line, disc or triangle, for example, may elect itself to ‘step forward’ from the shapes that surround it. The viewer attempts to follow this self-initiated dominance and its effect complexifies and expands, becoming musical and metrical – the visual equivalent to a beat or tempo.

Stepping back a few paces, the viewer might then attempt to take in the entirety of the picture only to experience an inability to find a single point of focus. Movement, shimmering, a sense of perceptual vertigo, always instigated by the work itself, creates a profound sense of presence and pictorial identity or personality.

The relationship between looking and seeing has both been denied its usual expectations and certainties, and heightened. It is not that the eye has been overwhelmed, exactly. More that the viewer has been made aware of an immensity of visual possibilities: an experience not dissimilar to looking at the stars in a clear night sky, or the expanse of the sea, or of clouds. The infinity of visual experience, in fact, that we encounter in nature.

When the historian and critic Robert Melville reviewed Riley’s seminal exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London, in 1971, for New Statesman, he pronounced the now famous and enduringly accurate verdict that: ‘No painter, dead or alive, has ever made us more aware of our eyes than Bridget Riley.’

Less famously, but with equal prescience, the writer Vernon Lee (nom-de-plume of Violet Paget) described in her 1903 essay Psycholog y of an Art Writer (Personal Observation) an approach to aesthetics and art appreciation that anticipates the cumulative development of ideas that has guided the art of Bridget Riley. ‘I tried to get to the bottom of the origins of art,’ writes Lee, ‘of its influence, the vicissitudes of various schools, the evolution of form. And, in doing so, I approached the work of art with an absolutely objective spirit. In other words, I looked at it with every last scrap of my attention.’

In a conversation with art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon, first broadcast on BBC Radio 3 in 1992, Riley described ‘the evolution of an abstract art whose vocabulary was independent of traditional cultural associations.’ Within Riley’s art this observation is axiomatic. ‘But the point about a visual language is that it must be expressive, that these elements – squares, circles, triangles, contrasts, harmonies, etc. – could express something when they were released from the burden of having to serve as agents for other meanings.’ In short, a visual language in abstract art that expressed only itself, but in doing so evoked sensations the viewer might encounter in their sensory experience of the world.

An early black and white painting by Riley, Fall 1963, reveals the immediacy and visual intensity of her developing enquiry into the relation between looking, seeing, perception and painting. Looking at the painting from top to bottom, the gaze follows the undulations of black and white lines as they tighten towards the work’s lower edge. In a relatively short time, the viewer becomes aware of descending horizontal bars of visual disturbance or shimmering that emerge from the vertical undulations. This, in turn, creates oscillations of movement, left to right, within the troughs of their fall. The painting thus releases its own autonomous movement, confounding a single experience of the work and even appearing to introduce the illusion of colour.

To look at Fall ‘with every last scrap’ of attention, as Vernon Lee proposed the act of looking, is therefore in one acute but meaningful sense to look at the act of looking itself.

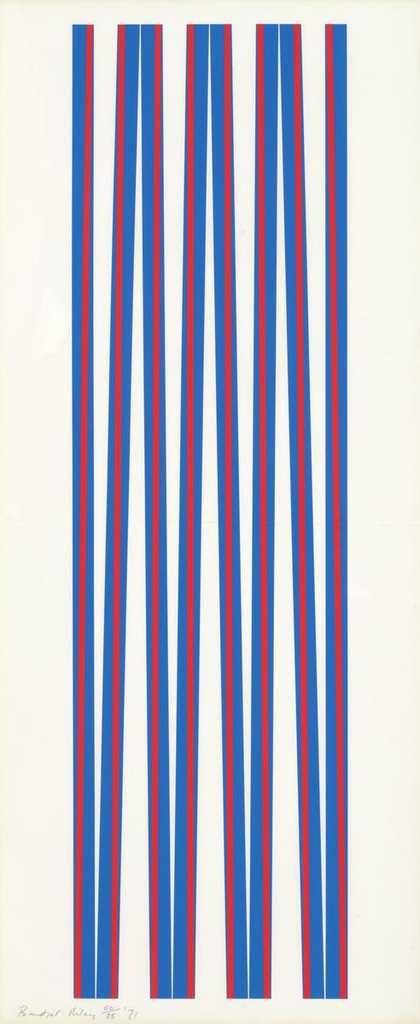

Bridget Riley

Elongated Triangles I (1971)

Tate

Riley’s profound study of French painting from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, notably the work of Seurat, Renoir, Monet, Bonnard and Cézanne, is the principal art-historical basis from which her own work proceeds. An extrapolation of the ideas, methods, processes and experience developed by these painters is taken by Riley beyond the possibilities afforded by their times, and into the renewed capacities and possibilities of abstraction in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

In her essay Seurat as Mentor (2007), Riley recounts the French painter’s vital influence on the development of her own methodology and early black and white paintings. ‘It became clear that one’s first task as an artist is simply this: to create a way of working, to discover doing and to establish the terms upon which a creative dialogue could be sustained’, she writes. ‘From Seurat I took the example of method rather than the method itself.’

As the enfolding and compelling energy of her art derives from the relation of looking to seeing and making, so the influences of memory and recollection are enmeshed or deeply sewn, integral, within this process. Series of studies lead to groups of paintings, each pursuing the development of an idea through formalistic and pictorial stages in a manner that might be likened to a process of aesthetic calculus. But this ‘calculus’ is never coldly mathematical or formalistic. Vitally, the created work admits the vagaries, disjunctions and unexpected interruptions that occur within human experience no less than in nature. In this, Riley’s art maintains close affinity to the relations between memory, perception and nature so meticulously scrutinised by the writer Marcel Proust, whose works were likewise a great influence upon her own. Of particular importance was Proust’s celebrated observation: ‘Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.’

In her conversation with Graham-Dixon, Riley recounted the progression of her work from her black and white paintings of the early 1960s (‘about states of being, states of composure and disturbance’) towards the introduction of colour later that decade, and the relation of colour to both visual sensation and the recollection of experience. She cites Late Morning 1967–8 as one of the early colour works in which she was ‘beginning to find my way with a whole host of sensations to do with colour.’

In Elongated Triangles 1 and Elongated Triangles 5 (both 1971, screen prints on paper) the relation of colours to both composition and to one another create multiple visual sensations. Verticals penetrated by descending and ascending sharply pointed triangles rearrange the dynamics of the composition and relations between the colours. On prolonged looking, these rearrangements become increasingly internal and serial, working both across the composition and vertically within it, creating depth according to both the width of the individual stripes of colour, and the alternating ascent and descent of their extended etiolated forms. The more the viewer searches for a ‘stable’ reading of their emphatic presence, the more it eludes them. What seems a straight vertical upright line is perceived as being at an angle. Likewise, within the colour sequence, an apparently stable vertical begins to incline.

The supposed point of visual resolution – which the eye determines as a horizontal across the centre of each work – appears to dissolve into perceptual non-alignment. And yet, despite these interruptions, created by and within the work itself, each of these works remains solid, firm, coherent and rhythmically dynamic. Both of these Elongated Triangles affirm Riley’s statement that ‘Art has to be expressive of the urgency and failure, love and inadequacy that drive human endeavour.’ In such manner, Riley’s work proceeds towards, rather than from, an experience of meaning.

Two recent paintings by Riley, Concerto 1 2024 and Concerto 2 2025 are joyous, monumental and thrillingly alive with softly resonant colour – a palette that abuts pale pink, pale blue, white, orange and peppermint green. Both of these Concerto paintings comprise vertical stripes that in turn are composed of three abutting stripes, two of the same colour containing a central stripe of a different colour: pink, blue, pink, for example, followed by peppermint green enclosing pink, followed by the metrical beat of a single white vertical. The colours both relate to and inform one another – the warmer colours appear to come forward, the cooler to recede; pairings and trios of warmer colours then emerge like visual chords, while stimulating a relay of movement within the painting as a whole.

Concerto 2 expands and massively complexifies these visual sensations, through the introduction of sudden arrests with the three colours comprising a vertical stripe, and the continuation in a different set of three colours. While operating across a relatively small selection of colours, an immense array of chromatic variations appear, which in turn – due to the arrests and changes of colour – create dramatic and rapid autonomous movement within the painting. The surface begins to advance and recede, while the colour changes confound direct perception, becoming at times after-images, sudden visual vacancies, that seem to ascend or descend across the height and width of the painting.

In her short essay The Pleasures of Sight, Riley concludes with a rare personal statement about her art that has held true since first published in 1984: ‘More than anything else I want my paintings to exist in their own terms. That is to say they must stealthily engage and disarm you. There the painting hangs – deceptively simple – telling no tales as it were – resisting, in a well-behaved way, all attempts to be questioned, probed or stared at and then, for those with open eyes, serenely disclosing some intimations of the splendours to which pure sight alone has the key.’

A display of works by Bridget Riley runs 21 July 2025 – 7 June 2026 at Tate Britain. Concerto I was presented by the artist in 2025, Elongated Triangles I was presented by the executors of Adrian Austin in 2021.

Michael Bracewell is a writer who lives in London.