Liliane Lijn in the exhibition Arise Alive, mumok, 2024 with Three Line Koan 2008 (left) and Mars Koan 2008 (right)

Photo: Georg Petermichl / mumok © Bildrecht, Wien 2024

JENNIFER HIGGIE Your first solo show was Echolights and Vibrographes at La Librairie Anglaise in Paris in 1963. What did it include?

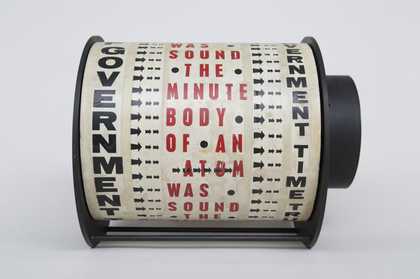

LILIANE LIJN In the show were the kinetic Poem Machines 1962 –8; Echolights 1963, which comprises a projector with a rotating lens that illuminates a pattern on the surface of a block of Perspex; and Vibrographe 1962/2019, which consists of two rotating metal drums covered with parallel Letraset lines. There were also three Perspex negative reliefs: Cuttings 1961, and Yellow Drilling and Double Drilling, both 1961, in which shadows are cast by cuts or drilled holes. This transforms the negative spaces into positive forms, creating the illusion of solids.

JH How have the themes and materials you explored in that exhibition developed in the decades since?

LL My interest in making Vibrographe was optical: spinning lines becoming vibration, the possibility of interference generating colour. Poem Machines grew from the Vibrographe, the lines becoming letters and words. The interplay between lines and letters deepened my interest in perception. I wanted the written word to be seen as the energy of sound. Meaning remained latent in the unreadable blur of spinning words, but when I made my first Linear Light Cylinder in London in 1967, I realised that an oscillating, reflected line of light was also a form of language. Echolights developed into Liquid Reflections 1966–8. In both works, I explored my fascination with reflections and shadows. The idea of visualising a photon of light led me from injecting plastic lenses onto the surface of a block of Perspex, illuminated through a revolving lens, to fabricating light boxes with Perspex fronts, framed with randomly blinking lights.

JH Were there other artists exploring the possibilities of movement in sculpture at the time, with whom you were in dialogue?

LL In Paris, there was the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (Visual Art Research Group, GRAV). I was interested in what François Morellet and Julio Le Parc were doing; I became acquainted with their work in 1967 at the exhibition Lumière et Mouvement (Light and Movement) at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

Liliane Lijn

Liquid Reflections / Series 2 (48”, 40”) 1966–8

Courtesy the artist and Sylvia Kouvali London / Piraeus. Photo: Stephen Weiss

JH Which artists have particularly influenced and inspired you?

LL I was interested in the ‘cut-up’ technique, practiced by the Beat poets, which I felt was related to surrealist automatic writing, and also the Greek kinetic artist Takis’s science-related magnetic sculptures. I spent part of the early 1960s in New York, then very soon after my first solo exhibition, I went to live in Greece – in some ways cutting myself off from the kinetic and op art movements.

JH How would you describe the relationship between written and visual languages in your work?

LL Writing has always been important to me; it’s a way of bringing the unconscious to light. Words are the material of thought, and writing is a fine way of clarifying one’s thinking. I have always felt that written and visual languages are intertwined.

JH What dictated the choice of words and poems that you incorporated into your sculptures?

LL The cylindrical forms of Poem Machines, and later the conical Poemcons 1968–90, dictated the length of the texts, although I was mostly drawn to poems that reference the cosmos, spirituality and science.

Liliane Lijn

Linear Light Column 1969

Courtesy the artist and Sylvia Kouvali London / Piraeus. Photo: Richard Wilding

JH Light has long been a recurring material and metaphor in your work. Could you outline its significance?

LL Light is the great communicator. Until recently, all our information about reality, our world and the universe, has been through our study and understanding of data gleaned from the electromagnetic spectrum, whether through our own senses or by means of the tools we have created.

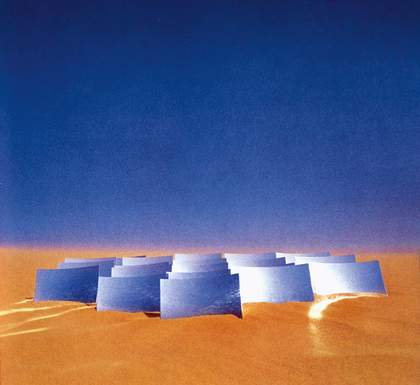

I love looking at the sky in all its varied moods and at the clouds that adopt multiple forms. I began by being fascinated by reflections and shadows, how light reacts with different materials, and in particular transparent material, such as glass or clear plastic. This led to works such as Liquid Reflections, which is a meditation on cosmic forces, including gravity. I thought of light as code, both in the Linear Light Columns 1969 and works such as Zero-Gravity Koan 1969/2004, in which light is perceived through planes of fluorescent Perspex as oscillating lines that replace the material volume of the conical sculpture. Discovering prisms was a spiritual experience for me, a clearing of the mind. I saw the many diverse forms of these tools for vision as the heads of figures – actors in arcane dramas.

With Homage to Milarepa 1972 and In the Valley of Darkness 1973, I began to create the dramas that climaxed in Conjunction of Opposites 1983–6 –two large, mixed-media, performing sculptures that enact a computer-controlled, six-minute drama, which includes movement, song, the transformation of sound to light, and a laser display. I also made a series, Prism Stones 1977, with which I tried to heal the divide between nature and technology by melding optical glass prisms to natural, timeworn stones. This series eventually led to Sunstar: begun in 2005, it is an ongoing ecological work that uses prisms to create solar installations in the landscape. Light is not only a metaphor in my work.

Liliane Lijn

Saurian 1978

Courtesy the artist and Sylvia Kouvali London / Piraeus. Photo: Richard Wilding

JH What role has spirituality played in the evolution of your work?

LL I think of light as a spiritual guide. I have also been fortunate to have visions that have guided and kept me on what one could call a spiritual path in my practice as an artist.

I was not yet 20 when I saw a reflection of myself in a floor-to-ceiling window at the airport one night. Seeing the airfield and mountains reflected as if they were inside my body, I realised my own emptiness. I had a similar feeling when I was experiencing painful period cramps. Pain became a portal through which I could have an out-of-body experience. Somehow, by entering and accepting my own physical pain, I felt an overwhelming sense of compassion for the pain of others.

In 1964 in Paris, feeling grey and depressed after a quarrel, I was surprised by a feeling of illumination, as if a brilliant flash of colour had wiped my mind clean. Many years later, in 2015, I saw photographs of the Lukhang murals in the Sixth Dalai Lama’s temple in Lhasa, Tibet, which depicted monks using a crystal positioned so that the sun could send spectra into their eyes. William Burroughs told my friend, the poet Nazli Nour, and me that he thought we were Tibetan reincarnations. She would later marry a Tibetan monk and together they founded a Tibetan Buddhist centre in Berkeley. In 1963, I left the excitements of the art world in Paris to study the teachings of Milarepa – the 11th-century Buddhist Siddha – in an effort to purify myself.

JH Your transformation of materials could be described as alchemical. What is the role of alchemy in your thinking?

LL I think of alchemy as a spiritual goal, the transformation of self. Artists can be considered alchemists when they transform raw materials in the cauldron of their imagination. In 1969, I wrote: ‘The artist creates by assembling atomic structures in such a way as to intensify their radiation. The idea behind the work becomes energy through the density of the material used.’

Liliane Lijn

Sky Scroll II 1959

Courtesy the artist and Sylvia Kouvali London / Piraeus. Photo: Lewis Ronald

JH In 2005, your deep immersion in science led to a residency at NASA. What do you see as the relationship between science and art?

LL They’re two areas of endeavour that lead human beings to a state of higher consciousness. I find both science and technology exciting, because, in these areas, people are pushing boundaries with their research. How discoveries and new materials are used is then up to politicians and the commercial sector. There should be more of a relationship between these two creative pursuits than there is. There are so many specialities in science that even scientists working in similar areas sometimes find it difficult to understand each other.

JH What are the latest technological developments that have interested you?

LL I have been inspired and intrigued by aerogel, a silicon dioxide that is only two per cent matter and 98 per cent air. I have explored the way it reacts to light in a series of works, Stardust Ruins 2008. Although a block of aerogel may feel solid, it can’t reflect light in the way solids normally do, so projecting images of my travels on to fragments of aerogel appear as changing, moving colours (Heavenly Fragments 2008). It dissolves reality, confirming the Buddhist claim that reality is illusory.

In 2012, I began working with Vapourshield, a composite of mica and stainless steel invented by my husband, Stephen Weiss, for use in non-ferrous casting. I poured molten glass onto a sheet of it to see how the two materials might react – the glass exploded into a strange bubbling dance. The resultant materials were very fragile and had to be cast into clear resin blocks to survive. Positioning them in resin blocks allowed me to create Catastrophic Encounters 2022.

In 2014, I was asked to create a permanent installation for the Museo della Canapa, a museum dedicated to hemp in Sant’Anatolia di Narco, a small Italian town near Spoleto. I was given samples of old and new pieces of cloth and started by spinning each of them with my fingers. I noticed that some of the pieces lifted, whereas others wrapped into a vortex. Concurrently with a residency at APC (Laboratoire Astroparticule et Cosmologie) in Paris and EGO (European Gravitational Observatory) in Pisa, I developed the work into Gravity’s Dance 2019, a six-metre-diameter levitating black cloth, its edges outlined with LED light.

Liliane Lijn

Brooding Head 1986–90

Courtesy the artist and private collection London. Photo: Lewis Ronald

JH How has feminism shaped your approach to being an artist?

LL Throughout my life, I’ve been infuriated by the attitudes of most men and the general repression of women artists. As early as 1960, I understood that feminism might heal the rift I felt between my body and my mind. My tools were geometry and light, and the perception of language. I think it’s very important that women have their own spiritual power. I chose to reclaim that power in my work.

JH The largest ever survey of your work, Arise Alive – which includes installations, sculptures, painting and moving images from 1959 to the present day – opened in 2024 at Haus der Kunst Munich, then travelled to mumok in Vienna, and will open at Tate St Ives in May. How has it been, seeing so much of your work exhibited together? Has it inspired new ideas?

LL It’s allowed me to see more clearly the path I have taken. Seeing the works together has made me more conscious of who I am as an artist. It’s too early to tell whether these shows will have inspired new ideas. I am more inspired by what I see in everyday reality.

JH Each iteration of the exhibition has been slightly different. Why is this?

LL The differences have arisen from the diverse gallery spaces and the personalities of the curators. Although the square footage of the spaces in Haus der Kunst and mumok are virtually the same, their layout is completely different. The new Tate St Ives gallery is somewhat smaller. However, the director, Anne Barlow, is still planning to include large works such as Electric Bride 1989 and the Conjunction of Opposites: Woman of War and Lady of the Wild Things 1983–6. These works are mythic and, if not specifically Cornish, they tap into universal archetypes found in the collective unconscious.

Liliane Lijn

Aluminium Koancuts 1971

Courtesy the artist and Sylvia Kouvali London / Piraeus. Photo: Liliane Lijn

JH How important is the engagement of the viewer with your work?

LL Very. It is only through the engagement of the viewer that art moves from being the expression or discovery of one individual to being a conversation that may illuminate and bring insights and joy to others. I have made several works that require the viewer to become an active participant, either by altering the work – as in Crystal Clusters 1972, Poemcons, Koancuts 1971, Landlines 1973 – or becoming an active part of the work, as in Power Game 1974–ongoing.

JH Your autobiography Liquid Reflections will be published by Hamish Hamilton in March this year. It focuses on your development as an artist in Paris in the 1960s. Why did you feel that part of your story needed to be told?

LL Liquid Reflections relates the wondrous yet painful adventure of becoming an artist. It is a slice of my life, the struggling beginnings of a woman artist at a time when girls were not supposed to be artists. It may be difficult for young women artists today to imagine what it was like for us in the 1960s. I hope that my book will keep that memory alive.

Liliane Lijn: Arise Alive, 24 May – 5 October.

Jennifer Higgie is a writer who lives in London. Her latest book The Other Side: A Journey into Women, Art and the Spirit World is published in the UK by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Curated by Emma Enderby with Teresa Retzer (Haus der Kunst) and Manuela Ammer (mumok) and adapted for Tate St Ives by Anne Barlow with Dara McElligott. Organised by Haus der Kunst München and mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, in collaboration with Tate St Ives.