P.Staff

Weed Killer 2017

© Courtesy of the artist and LUX, London

‘No eyebrows. No eyelashes. When it rains the water will run straight down into my eyes’, wrote artist, writer and social activist Catherine Lord before her hair fell out during radiation and chemotherapy treatment, which she described as like ‘mainlining weed killer’. ‘No oil, no moisture, no life.’

Propelled by her diagnosis of breast cancer, Catherine adopted an online persona named Her Baldness. Existing mostly in emails to friends and colleagues scattered across North America and Europe, it was not an online persona as we understand the term today. Her missives, sent via Listserv, would come to form a series of pointed diary entries, which would eventually form her book The Summer of Her Baldness: A Cancer Improvisation (2004). Her Baldness is an irreverent, biting performance of both patient and dyke; it is an evisceration and a polemic.

I read The Summer of Her Baldness in 2015, when I was attempting to convince Catherine to write about one of my own artworks. I was trying to be a good student. My friends Lisa and Ian had just died. I had recently moved from London to Los Angeles, following a tumultuous breakup. I was transitioning, male to female – whatever either of those words mean.

What happens when you read a memoir, an account of someone else’s experience, and relate it intensely to your own life? I had never had cancer, but I felt myself to be living in the kingdom of the ill. In Catherine’s – or, I should say, Her Baldness’s – account, she details the clash of personalities in support groups, her ambivalence about Western medicine, her struggles to maintain her relationship with her partner, and her bemusement when she is mistaken for a ‘sir’. Catherine and I became friends, and I asked her if I could adapt a section of the book into an experimental film. She told me that, as the writing had been published, she didn’t own it anymore: I should use it in whatever way I wanted, or needed, to.

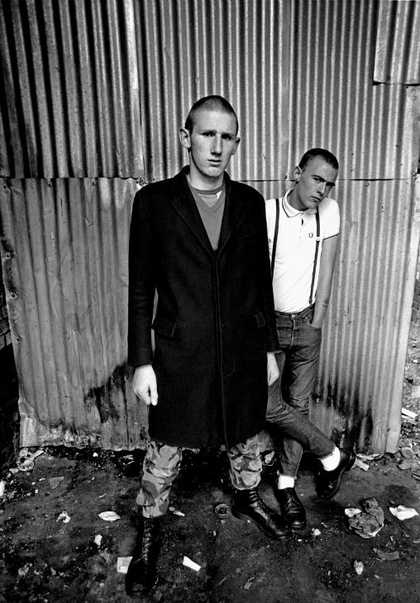

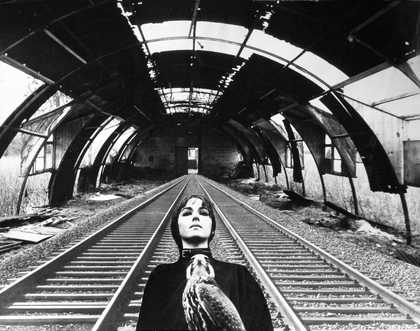

Three performers appear in my film Weed Killer 2017 – Debra Soshoux, Jamie Crewe and me. We filmed over three days, in three locations around Los Angeles. Debra performs a monologue adapted from Catherine’s book. Jamie performs the song To Be in Love (1999) by Masters at Work in a Los Angeles gay bar to a crowd of mostly uninterested men. I appear enlivened by a high-definition thermal camera and rub hot lotion on my skin, adjust a wig, pour boiling water down cold chains. Eventually I dance a pas de deux with an industrial cement mixer. It churns liquid into a semi-solid, my bag of flesh not so dissimilar.

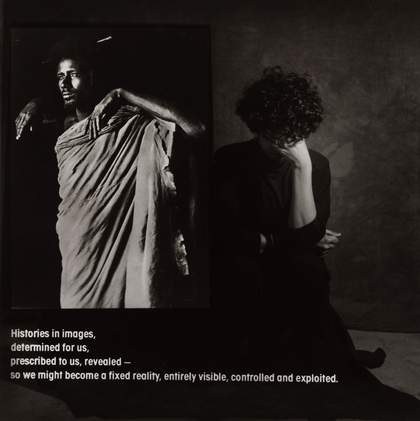

Weed Killer became a work about many things: illness, medicine and poison; gender signifiers, sexuality and the construction of community. It became about the performance and re-performance of someone else’s words, someone else’s experience. It featured heartbreak and love songs performed to ambivalent crowds, as well as skin and surface – both shimmering and irradiated.

I often think about the proximities to violence, immiseration, illness or exclusion that our desire to self-determination can entail. What is the good life? Why do we fight to survive – and at what cost?

Weed Killer was purchased with funds provided by the 2019 Frieze Tate Fund supported by Endeavor to benefit the Tate collection in 2020 and is on display at Tate Britain until June 2026.

P. Staff is an artist based between London and Los Angeles.