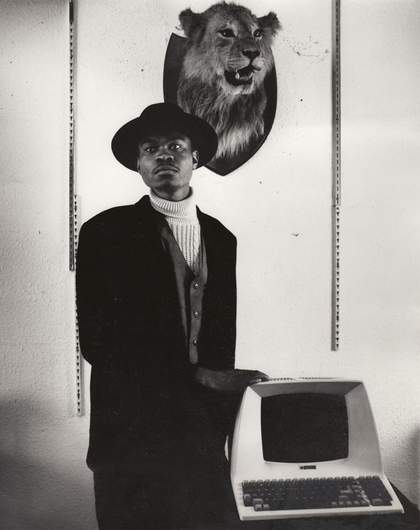

Yinka Shonibare in 1989 with a taxidermy lion head (‘I was mocking the colonial figure that would go to Africa and display their trophy’), and a computer (‘the height of modern technology’)

Courtesy of Yinka Shonibare. Photo: Edward Woodman

I was born in London, but many of my formative experiences took place in Nigeria, where I moved with my parents aged three. On Saturdays, I would attend a museum workshop for children where I saw traditional African art and the kinds of masks that had inspired Western modernists like Picasso. Given all the stories about these masks being ‘primitive’, I was fascinated by their aesthetic. Even as a child, I realised there was much more to them.

At that time, I also encountered some of the Benin Bronzes in Lagos, plaques and sculptures that had belonged to the Royal Palace of the Kingdom of Benin (in present-day Nigeria). I remember how I felt reading the captions and learning about the British sacking of Benin, which seemed to have been so violent. When I exhibited in the Nigerian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2024, in the midst of debates around cultural restitution, I made work in response to the Bronzes. Over 40 years later, those images from childhood came back into my head.

I returned to London in 1980, aged 18, and decided at the last minute that I would study art rather than law. My parents were not pleased. I have three siblings – a banker, a dentist and a surgeon – and, like most middle-class Nigerian families, my parents had expected me to become a lawyer or something like that. However, on arriving in London, I suddenly found myself in a place where I was not judged by anyone. I felt I had the freedom to express myself.

At art college, I trained first as a painter, making work about Russian poli- tics. One of my tutors said to me ‘You are of African origin – why aren’t you produc- ing authentic African art?’ I said ‘What do you mean by authentic African art?’ At the time, people didn’t understand African culture; they thought it was old-fashioned and traditional. But really, popular culture was similar in Nigeria and the UK.

I used to hang out at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, which was a happen- ing space in the 1980s. I saw lectures by Edward Said, as well as the work of Jenny Holzer. She made me realise that you could make art from anything, and I became interested in the use of non- traditional materials.

One day, I went into a shop in Brixton Market where they were selling African textiles, and I asked about the fabrics. I had imagined they were ‘authentically African’, but I learned that they were inspired by Indonesian batik, produced by the Dutch, and eventually sold in West Africa. I thought: Great, that’s my authenticity. I started using these fabrics in my work and have included them in several pieces, including Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle 2010, which was exhibited on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, as well as works in Tate’s collection.

Not long after this, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I was struck by the fantastic project spaces opening all over London. In Vauxhall, there was City Racing, where many of the YBAs used to hang out, and people were taking over empty buildings after the recession and turning them into art spaces. There was a lot of energy and I wanted to be a part of it. My work was shown at a project space called Independent Art Space in Chelsea. Charles Saatchi lived nearby and one day he walked in, saw my work and was interested. He became the first person to buy a piece of my art. At the time, Saatchi was the biggest art collector in London, so if you were in his collection, your career would change overnight. That same week I joined Stephen Friedman Gallery. The rest is history.

Yinka Shonibare CBE is an artist who lives in London.