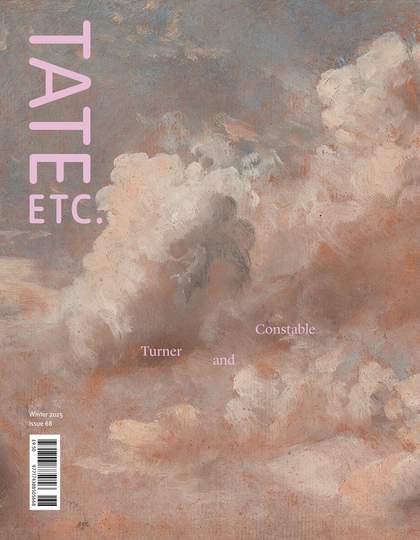

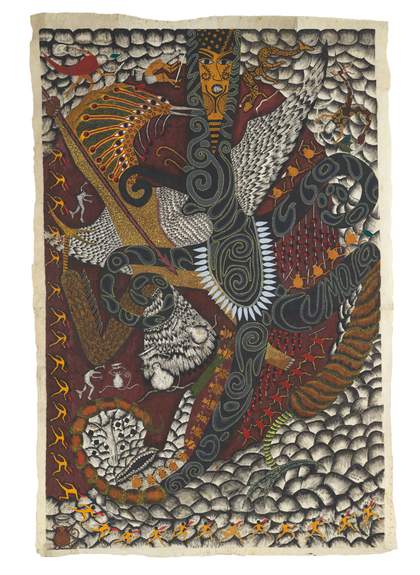

Santiago Yahuarcani

The Spirit of the Cumala 2023

© reserved. Photo © Tate

REMBER YAHUARCANI Where did the ideas come from for your painting The Spirit of the Cumala 2023?

SANTIAGO YAHUARCANI In 2023, when the opportunity came up for an exhibition at Centro Cultural Inca Garcilaso in Lima, Peru, I wanted to make the most of it as an Indigenous artist. I thought I should make something big and impressive, something interesting. I wanted to share our myths, our beliefs, our culture.

For many days I talked with my wife, Nereyda, and eventually I decided to make a work based on something that my late grandfather, Gregorio López, told me about: the cumala, a tree from the Amazon. It is used for wood, but its resin was also extracted and used in times of great need. You could extract the essence and ingest it to find out what was making someone sick. I thought the Western world would want to know these things about our people.

So, at night, I started to go into my imagination. Between one and three in the morning, the quietest hours in the Amazon, I would go into my mind and make an outline of the drawing in my head. At daybreak, I would start drawing. There was a lot of thinking and Nereyda contributed a lot of the ideas behind it.

RY The cumala has a ‘spirit-owner’, right?

SY Yes. My grandfather told me that the spirit-owner of the cumala is a white man with Western characteristics. He has blue eyes, and is of middle age. And this spirit is more or less like a scorpion, with a scorpion’s tail and arms.

RY Can you tell us about some of the images we see in the painting?

SY The spirit has a scorpion’s tail, and in the stinger there is another being with a stone head and a wide mouth. The character also has bird-like feet, and one leg seems to have a braided vine wrapped around it. His arms are curved, like the tail of a scorpion. He has no face, but wears a crown in which another character appears: a face of an ancestor who seems to be singing. And there are some symbols there too – the symbol of work, for example, which always appears in my paintings.

The spirit of the cumala is engaged in a fight with another character, a being that looks like a bird, seen on the left. We call him the Sarara spirit. He is the spirit of the shamans. Sarara carries a spear and is trying to pierce the heart of the spirit of the cumala. But he cannot do it. Why not? Because if you look carefully, all around the edges of the work are different beings who are dancing, walking, running. These are the armies of the cumala’s spirit. The spirit of the cumala – like the cumala tree –is very strong.

There are some other little beings that resemble red chilli peppers. These are the chillies that we burn in charcoal and use the smoke to drive away the bad spirits that exist in the Amazon. And if you look carefully, you can also see that the spirits are surrounded by stones. They are at the entrance to the tunnel of the spirit of the cumala, and the spirit is defending it, so that Sarara, the evil spirit of the sorcerers, cannot enter. Sarara will never be able to enter, because he is alone, without an army.

RY It’s important how these invisible characters become visible in your work. This whole universe of beings is actually alive, not just in your paintings, but in Indigenous territories – the lands of your ancestors.

How did you learn to obtain the natural dyes that you use in your work? And who taught you to identify the renaco tree in the jungle, and how to make llanchama parchment from its bark?

SY When I was six or seven years old, my grandfather would take me to the jungle to get the llanchama. He would remove the thin, green bark from the tree, and then pound it with machetes or mallets. I spent a long time with him, and by the time I was 20, I could obtain the llanchama myself.

As for dyes, in our community there are many vines, leaves, seeds and fruits found in the jungle that we use for our colours. Our grandparents have always used them, to paint their llanchamas and their faces for festivals and rituals. We also plant and grow things in our gardens, because some of these natural dyes are also medicines that the almighty god Buinaima has given us to use when we need them. Achiote, for example, is used to drive away evil spirits, and it’s also used to help with pain.

There’s a story about the creation of the world that says there was a young painter who used paints and the various materials and colours that exist in nature.

RY Yes, the creation myths speak of Fidoma, a god of painting, who painted the birds and the various beings that Indigenous people recognise today when we go to the chacra [small gardens or farms] or go about our daily life. Many people in the West, including art historians and art critics, believe that painting is a recent invention, but in reality it’s an ancient practice. What does showing your paintings achieve for your community? Is it about preserving traditions?

SY The work we have been doing, as a family, is aimed at preserving. This does not end with me – it will continue, because all our stories have to be passed down the generations. But above all, the paintings are about making the knowledge behind our culture known. I think the community see it as a great opportunity to make our work known to those who want to learn.

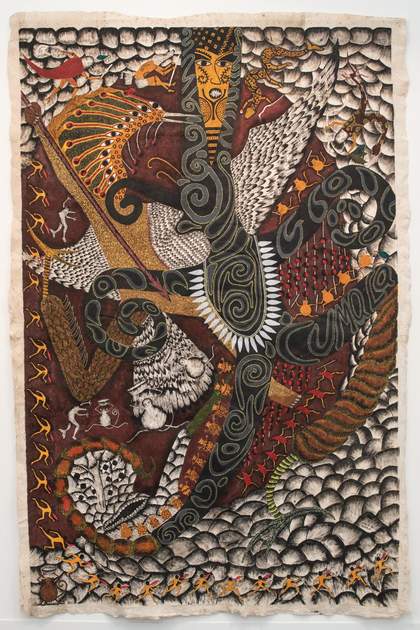

Rember Yahuarcani

Noche de Tabaco (Tobacco Night) 2025

© Rember Yahuarcani. Courtesy the artist and Josh Lilley, London. Photo by Eva Herzog

RY What’s your opinion of Indigenous youth now? Are they on the right track?

SY I’m 65 now, and I’ve been working my whole life. It has been a struggle all these years. I think my work has been trying to find where it belongs for so long, and I believe that moment has arrived.

I would like young people to think about what long-term work means. Things don’t just happen overnight. A person should find their own way: dream, create, imagine, become intoxicated, have experiences. An artist has to be a dreamer, a creator, a seeker. Sometimes we have certain ideas that cause the world to think ‘this person is not in their right mind’. I think that an artist must have some madness, something of everything.

RY I want to speak about the similarities and differences between our work. Yours starts with materiality that is strongly linked to the forest, and to traditions – making the dyes and canvas yourself. It’s a collective, family effort that involves getting up early, going to the farm with your children and grandchildren, preparing food. You have your own process and your own distinctive style, so much so that you are now identifiable within Peruvian contemporary art and within contemporary art globally.

In the past 15 years I have been developing a style that is more dreamlike, and more versed in issues such as unequal collaborations, the appropriation of Indigenous aes- thetics and knowledge by curators, thinkers, researchers and other experts from the Western world. Compared to your work, my work raises questions and brings about a revision of Western European artistic canons that are present in Latin American cultural institutions. Regarding similarities, many of the characters you paint in your work can also be found in my work, but with different corporealities, different movements, lights and textures.

SY We have different styles, but the same myths. It’s interesting that the styles have gone down well with the public. There was a time when I wanted to change the style of the paintings I am doing now, but many people said that I should not change, because this is the style that I am supposed to have. Maybe one day I’ll have a crazy idea and go off in a strange direction. But, for now, I’m staying with this same rhythm.

RY An exhibition of your work is now open at the Whitworth in Manchester. How does it feel to exhibit your work internationally?

SY I’m pleased, because people are beginning to see the importance of what my works transmit about our culture, our knowledge, our ancestors. That energises me; it makes me eager to keep working. I hope that the people will study our art deeply, because our mission is to make our culture known to the world.

RY I have just had a show at Josh Lilley Gallery in London, and to have these works presented in these contemporary art spaces validates our cultures. It makes ancestral knowledge contemporary. These works carry age-old knowledge that comes from Indigenous cultures that have been historically abandoned.

Our work is not just two-dimensional, like paintings. This is a historical process of political representation and self-representation by communities that have not had that for 200 or 300 years. I would love for people to look at the works and see that these Indigenous territories, such as the Amazon, are totally alive, and that they are governed by these beings that we paint. These Indigenous spaces are not territories in which living beings do not answer, or talk, or teach or feel. They have words, voices, and a presence that is closely linked to Indigenous societies. And we connect to them through tobacco and coca, which are our powerful plants.

We would like European cultural institutions and spaces to open up to these new works, to this new knowledge, and allow these voices to be heard firsthand.

The Spirit of the Cumala was purchased with funds provided by the 2023 Frieze Tate Fund supported by Endeavor to benefit the Tate collection in 2024. It is on loan to the Whitworth, Manchester for Santiago Yahuarcani: The Beginning of Knowledge, until 4 January 2026.

Rember Yahuarcani is an artist, curator and activist. His first solo show in the UK, Here Lives the Origin, runs at Josh Lilley gallery until 13 December.

Santiago Yahuarcani is an artist, Indigenous activist and leader of the Aimeni (White Heron) clan of the Uitoto people.

Translated from Spanish by Nuria Rodriguez Riestra.