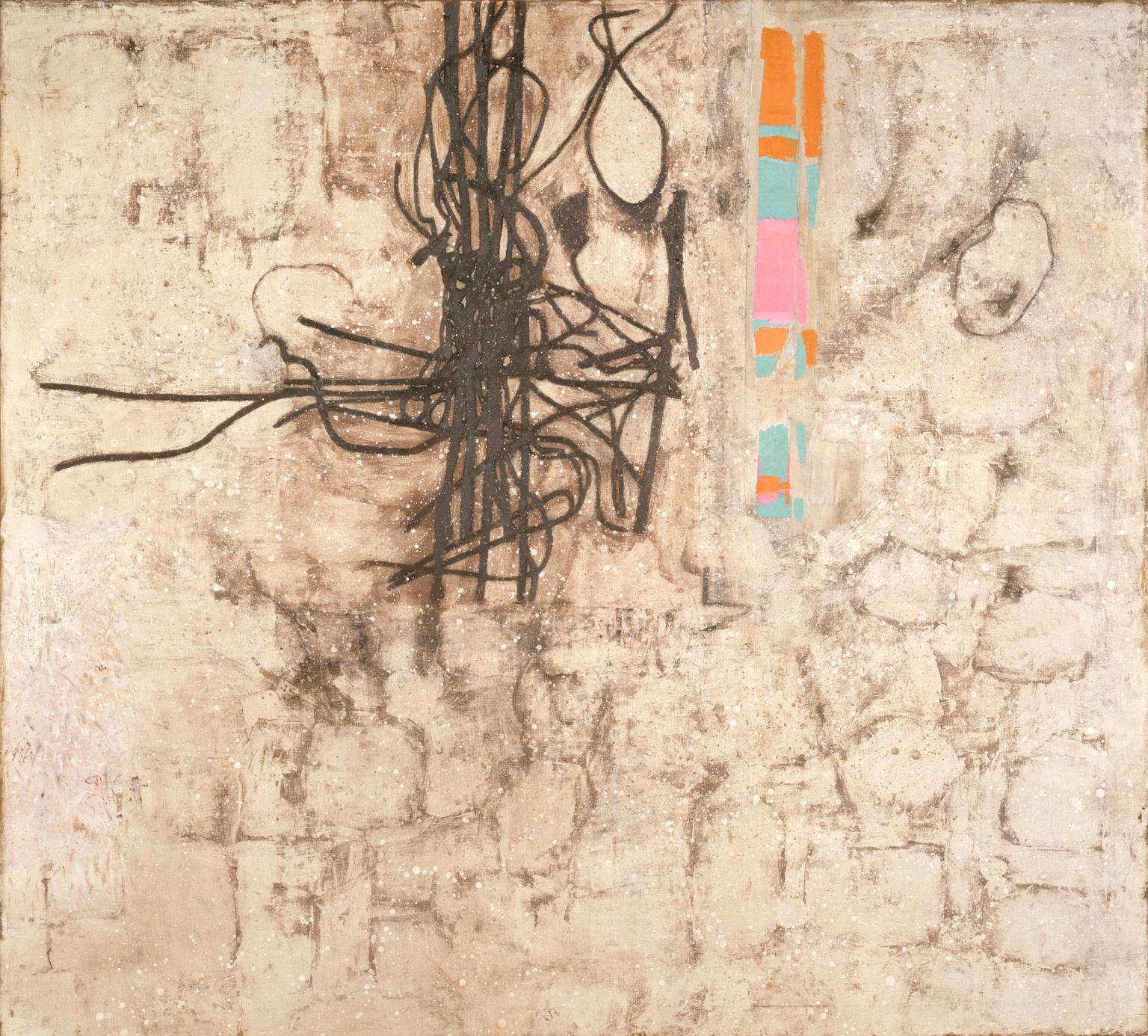

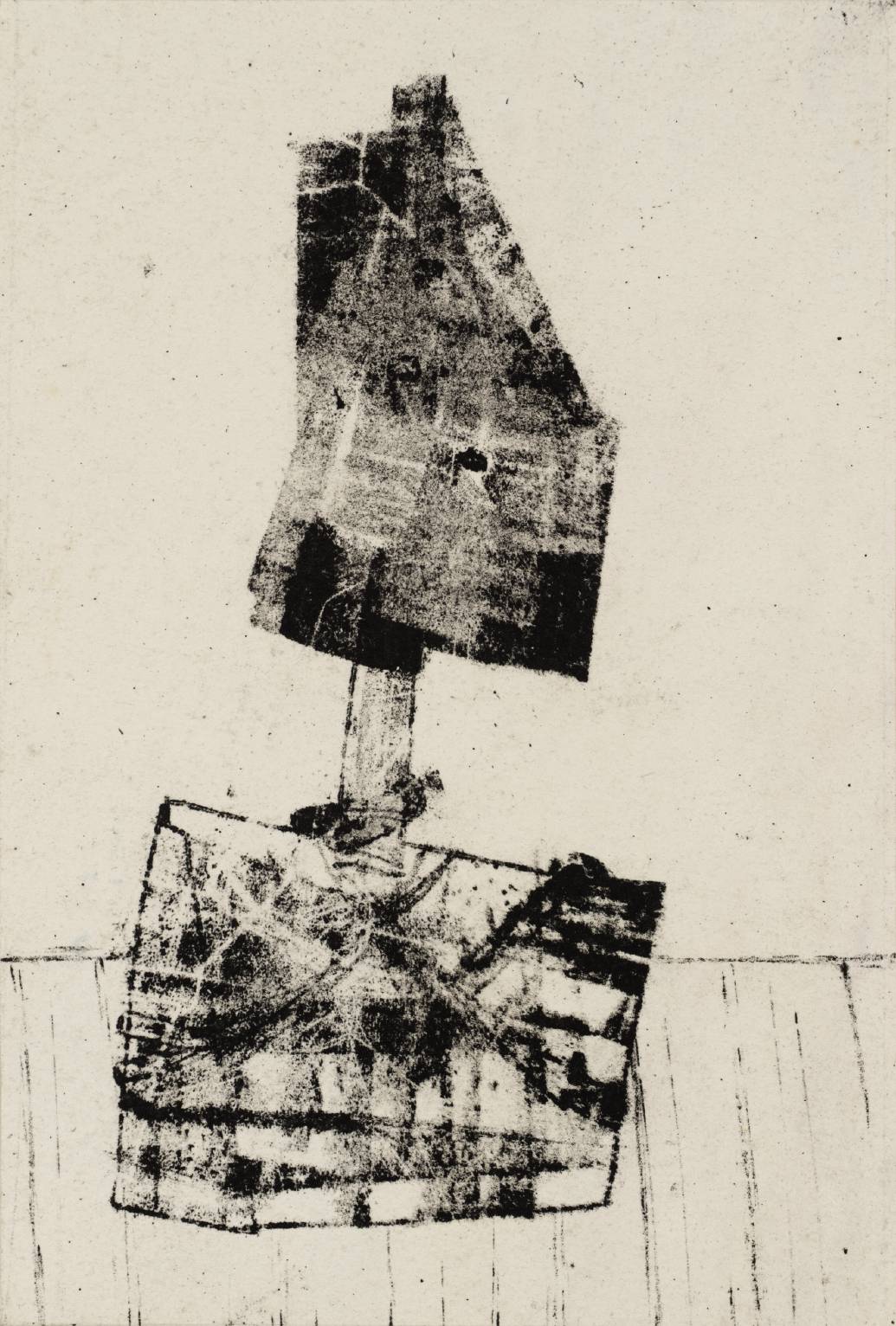

In the 1960s artists in Britain adopt a radical approach to question society’s values, merging art with life

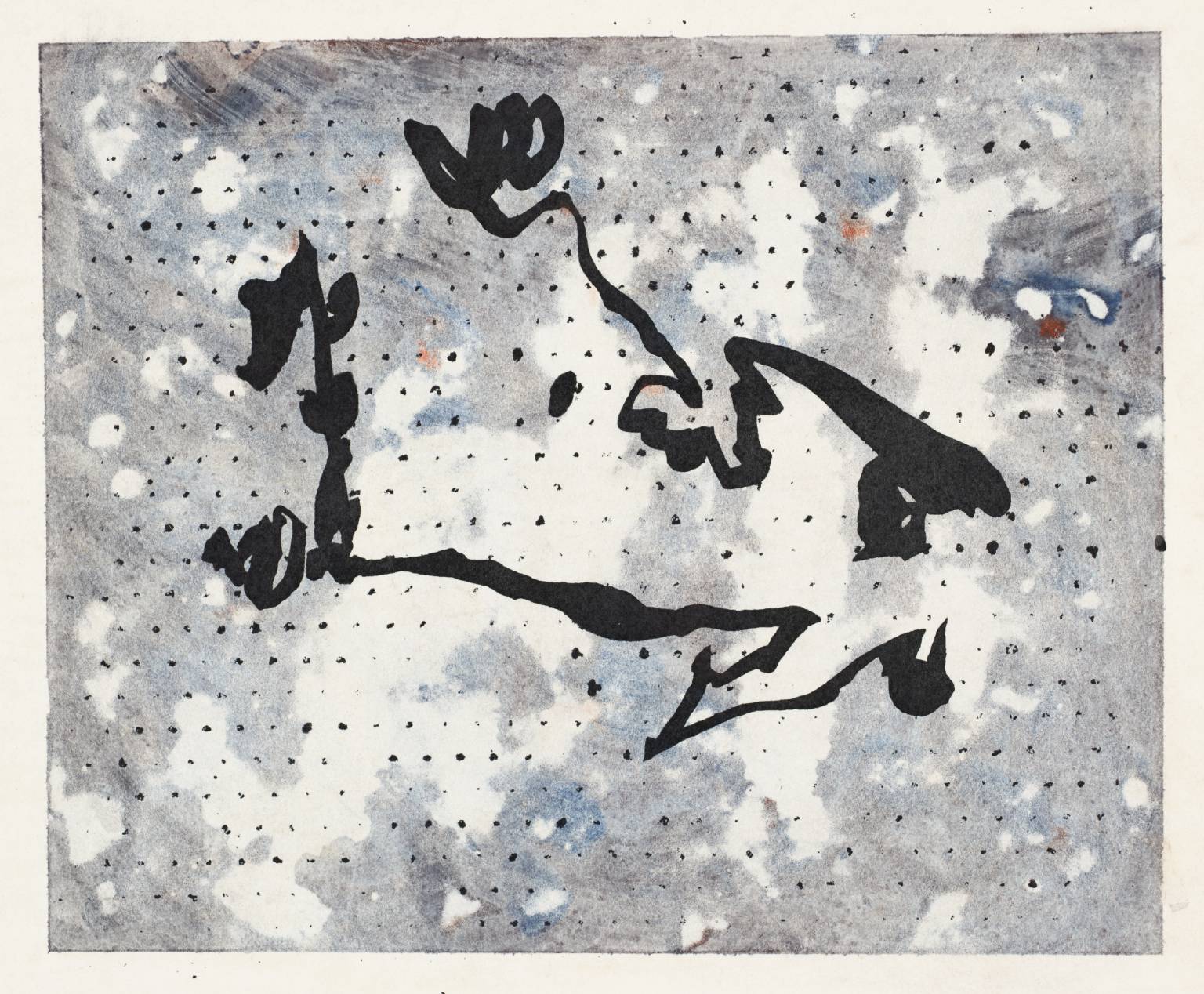

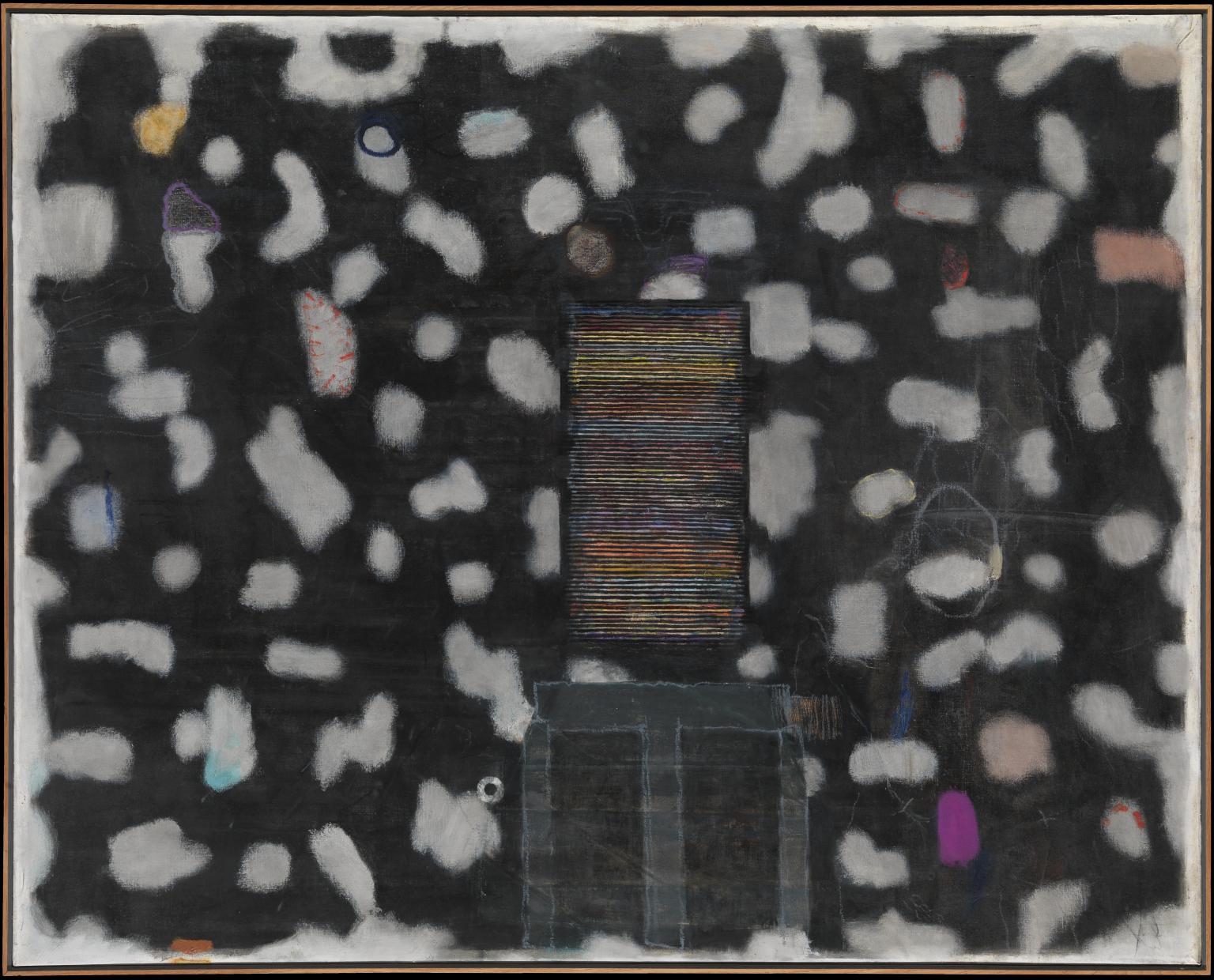

At this time, a growing activist counterculture is concerned about civil rights, the threat of nuclear war and interventions by the United States in Asia, Africa and South America. These calls for freedom and resistance anticipate shifts in art and youth culture. Some British artists become part of international experimental art movements such as Fluxus, which makes art out of actions. They use performance, poetry and any materials available to allow chance to shape the outcome of their work.

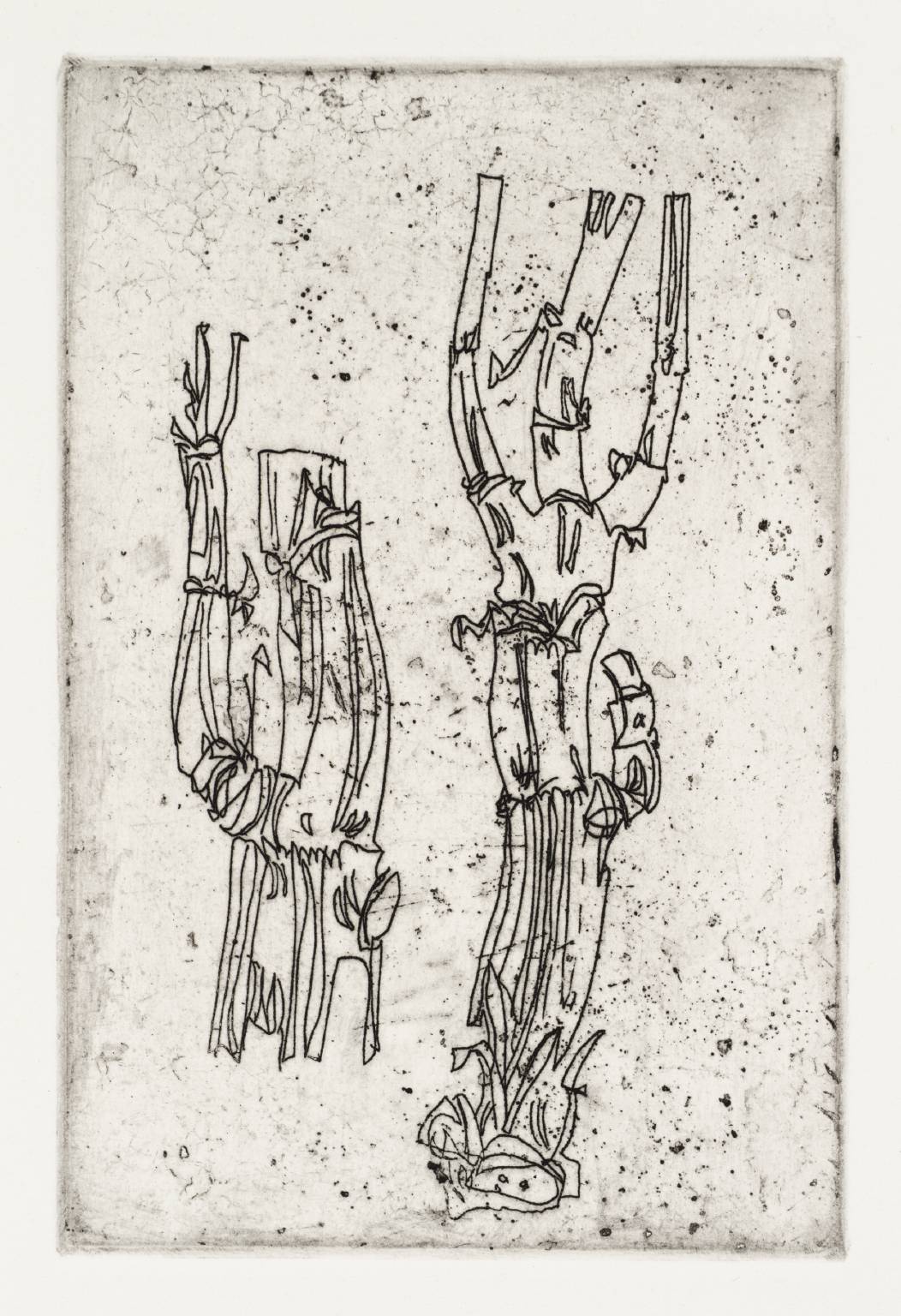

A pivotal moment is the 1966 Destruction in Art Symposium in London, co-organised by the German artist and activist Gustav Metzger. Over 50 artists, scientists, poets and thinkers from Europe and the United States come to London for a series of performances and discussions. They explore the role of destruction in art and how it relates to this new social and cultural era. Several of the works in this room reflect events and happenings that take place during the symposium.

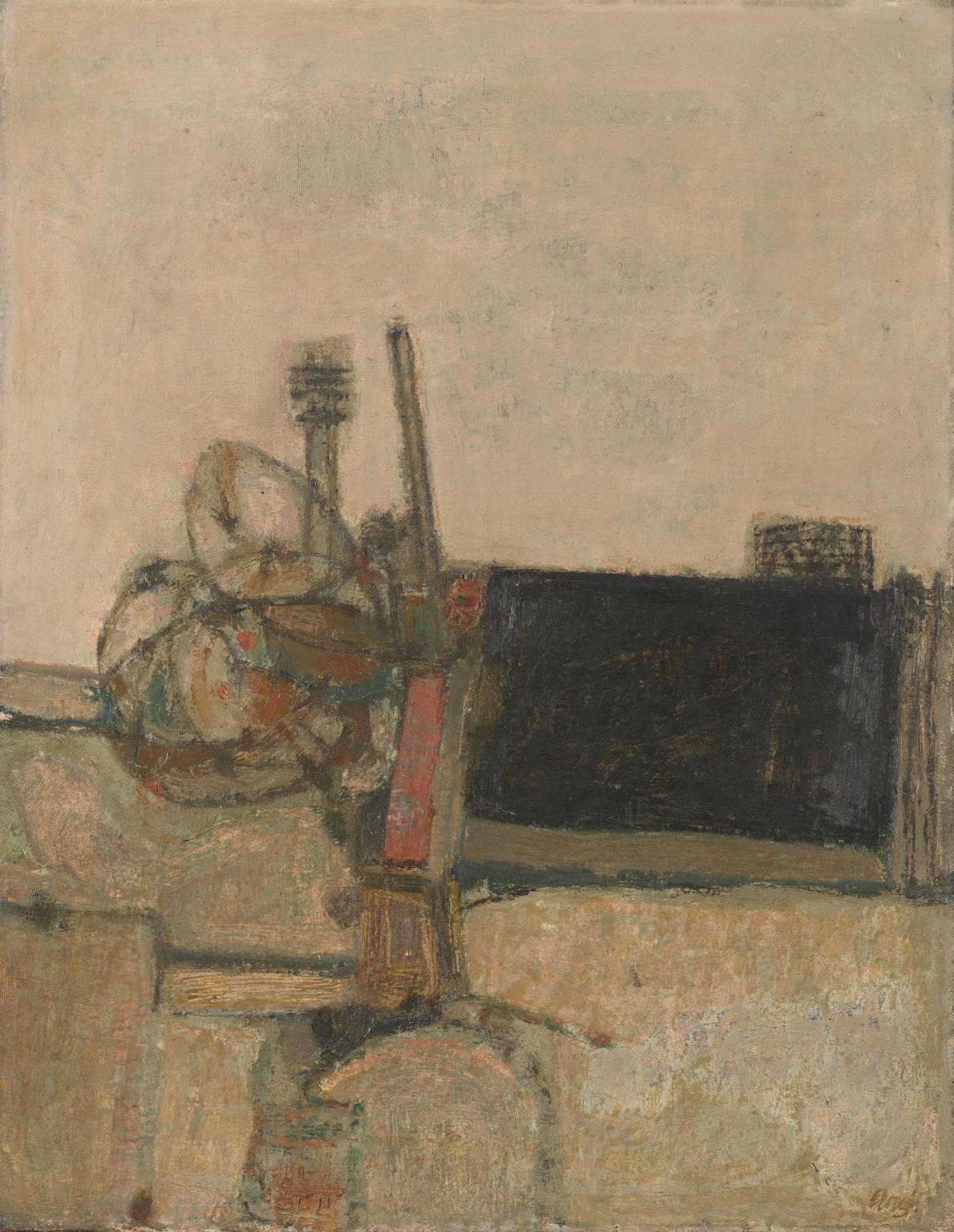

Some artists engage with scientific and technological developments. They experiment with kinetic sculpture: sculpture that moves. At times, these works aim to express fear of the way machines are used throughout society. Other works explore the vitality of life. The gallery Signals London is an important meeting place for South American and European kinetic sculpture artists in the mid 1960s. It provides a forum for artists who believe in ‘Art’s imaginative integration with technology, science, architecture and our entire environment'.

Art in this room

You've viewed 6/13 artworks

You've viewed 13/13 artworks