On August 24, 1939, Tate closed its doors to the public for the duration of the war. The building sustained bomb damage on several occasions over the following years; offices and roofing were destroyed as was all the glass in the building when the gallery was hit early in the morning on 16 September, 1940 and on 19 December, two incendiary bombs penetrated the roof and set fire to the floorboards in one of the galleries. In May the following year, a bomb landed in front of the building.

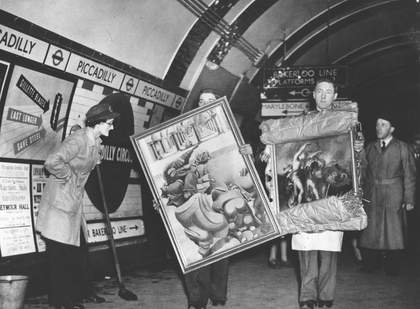

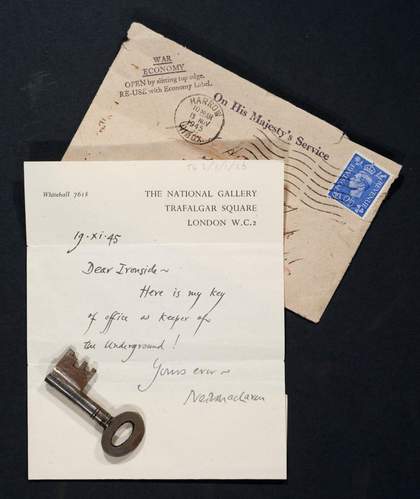

Traces of damage to the building are still visible on the gallery’s pock marked western wall in Atterbury Street - but fortunately, most of the art collection had already been dispatched to places of safety in the countryside. Other works remained in London, stored in disused London Underground tunnels at Piccadilly station. Along with the records and reports on such safe houses, Tate’s Library & Archive has a small plan of the location of the Piccadilly store, and its door key accompanied by a brief note (see image 4 in gallery above).

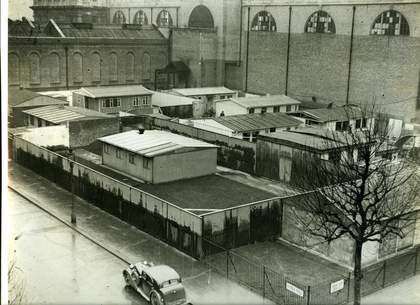

Of all the wartime items, one I find particularly fascinating is a photograph showing prefabricated houses sited on the ground next to the gallery (picture 5 above; these prefabs were where Tate’s 1979 North East Quadrant extension now stands - the part covered in Ivy).

These were the prototypes for the 160,000 prefabs built after WWII, designed to address the post-war housing shortage. No.1, the house on the corner with the smoking chimney was the first. Despite Churchill’s announcement that factories would soon be churning out these houses, they never went into production and this steel clad structure - the show house - was built entirely by hand.

The occupant of no.1 was Albert Deighton, a civil servant who had been invalided out of the RAF, and was given the chance to serve as a ‘guinea pig’ resident for no. 1 with his wife from November 1944. But in doing so, he had to sign the Official Secrets Act; he was not permitted to receive personal visitors or to discuss any aspect of the house, except with government officials, and especially not with the press. Reputedly, the houses were exceptionally well fitted - but in reality, condensation continually ran down the walls and froze in cold weather, and mould grew on the items stored in its ‘marvellous’ stainless steel cupboards. When these defects leaked to the press in 1945, Albert was blamed and almost lost his home. Fortunately, he was later exonerated. Reinstated to the civil service, he and his wife were then moved next door to a more habitable prefab just to the right of no.1 (seen with the workman fitting its roof).

Tate’s grounds weren’t only home to prefabs. The photo of a man in uniform standing next to a cabbage (picture 6) was taken on one of the local Westminster residents’ allotment plots for which the gallery’s gardens were repurposed between 1942- 46.