Rethinking inspiration between different cultures

Different world cultures have always been a source of inspiration for many artists throughout history. Although this has led to important artistic developments, it is a complex story that has rarely been carried out on equal terms.

On display you’ll see works by Pablo Picasso and Constantin Brancusi. These artists were excited by artworks from across Central and West Africa, as well as the Pacific Islands. Yet the source of their inspiration was often taken by force by colonial European forces. At the same time, artists around the world were being influenced by the European avant-garde. See how Wifredo Lam’s work was inspired by his time in Paris, but also by his own Afro-Cuban heritage.

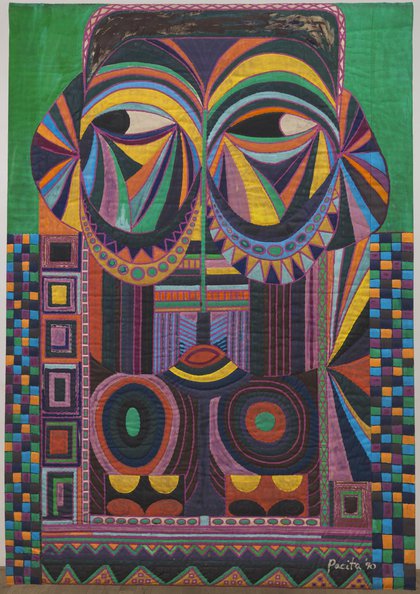

Also on display are artworks that question Western ideals of art and identity. Pacita Abad rejected her American art education and looked to her Filipino heritage to develop her style. In their works, Ellen Gallagher and Santu Mofokeng challenge the impact that white Western ideals of beauty have had on Black identity.