html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40/loose.dtd"

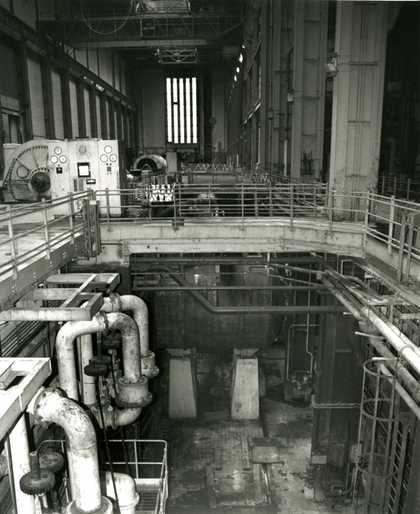

1. The Turbine hall

The vast hall at the heart of Tate Modern is probably the best-known space in the gallery. 35 metres high and 152 metres long, you could comfortably teeter seven London buses on top of each other in there.

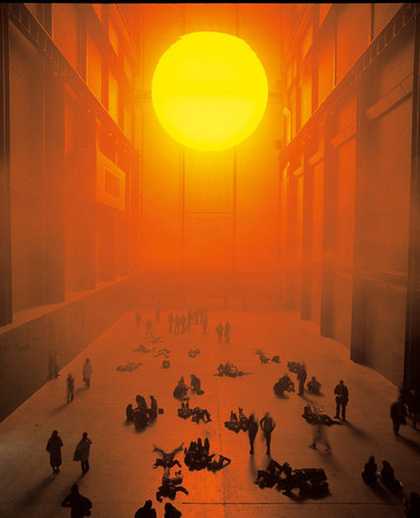

Though the Turbine hall has recently played host to headline-grabbing artworks, from the hanging sun of Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project to Doris Salcedo’s floor-cracking Shibboleth, in the mid twentieth century, it housed huge electricity generators as the main section of the Bankside power station.

When the building was converted into the gallery space we now know, architects Herzog & De Meuron retained many of the original features, from the unfinished brick walls and exposed steel construction beams, to the narrow vertical windows stretching up to the cathedral-high ceiling at each end of the hall.

Boris Charmatz, Adrénaline

Photo: Louise Schiefer © Tate 2015

Olafur Eliasson

The Weather Project 2003

Installation view, Turbine Hall at Tate Modern

Photo: Tate Photography © Olafur Eliasson

2. The chimney

Now firmly part of the London skyline, Tate Modern’s chimney first appeared on the south side of the Thames in the early 1950s. In fact, when the new power station was first proposed in the 1940s, its situation directly opposite St Paul’s Cathedral caused concern that it might impose itself too much on the view.

Architect Giles Gilbert Scott (the mind behind the red London telephone box) was employed to ensure the new power station did not compete with St Paul’s and he simplified the building into the low horizontal profile with its single brick chimney that we know today, very different to his other iconic power station in Battersea.

The Bankside chimney is 99 metres tall, just lower than the dome of St Paul’s, and is built entirely of brick. Best seen from the river, either on the Millennium Bridge, or on the boat between Tate Britain and Tate Modern.

3. The new Switch House

The Switch House is the new extension to Tate Modern, built on the site of the old switch house of the power station. Designed by architects Herzog & De Meuron, who did the original building conversion, it marries old and new technology to create 10 new floors of gallery space.

Nearly 170,000 bricks have been used to clad the extension, while inside concrete construction echoes the original boiler house and tanks. Look out for where the patchwork of bricks is perforated to let light in, and new nooks in staircases for resting, chatting and people watching.

Right at the top of the pyramid-shaped building is an open viewing terrace. Though no higher than the chimney, it has an unobstructed view down the river Thames and across London, from Canary Wharf to Wembley Stadium. Access is free, just use the dedicated lift from Level 1.

4. The Tanks

As the name suggests, the huge circular rooms to the south side of the Turbine Hall were once underground tanks to hold the oil that powered the turbine generators. Oil was chosen to fuel the station as it was seen as less polluting and difficult to manage than coal. Though it came with its own hazards (not least the fire risk), sinking the tanks into the ground was another way of reducing the visual impact of the building on the riverbank. Their rough concrete walls still bear the marks of their industrial past and remain the clearest reminder of the industrial history of the gallery.

Now fully excavated, they may not seem like normal gallery spaces, but like the Turbine Hall, they open up the sort of art that can be seen in Tate Modern. Instead of holding the fuel for the turbines, they now provide space for live art: performance, dance, film and discussion.