Each year the Turner Prize jury nominates a group of artists for an outstanding exhibition or presentation. The prize was first awarded in 1984. It was founded to encourage a wider interest in contemporary art and is named after Romantic artist JMW Turner, who had been innovative and controversial in his own time and is now considered to be one of the greatest British painters.

The Turner Prize is awarded to an artist born or based in the UK, celebrating recent developments in their work. The prize has consistently provoked discussion and debate on modern and contemporary art in the popular sphere in the UK, in part due to its focus on new art.

In 2007 Tate Liverpool hosted the Turner Prize, the first time the exhibition was held outside London. The shortlisted artists were Zarina Bhimji, Nathan Coley, Mike Nelson and Mark Wallinger, and the prize was won by Wallinger. The prize is now held at a venue outside Tate Britain every other year. Previous galleries include the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, Ebrington in Derry~Londonderry, and Turner Contemporary in Margate.

This year’s Turner Prize was awarded to Veronica Ryan on 7 December, during a live broadcast on BBC television.

In 2023 the Turner Prize will be presented at Towner Eastbourne.

Heather Phillipson

Phillipson’s multimedia projects include video, sculpture, installation, music, poetry and digital media. She describes her works as ‘quantum thought experiments’. They often carry an underlying sense of threat – a suggestion that, in the artist’s words, ‘received ideas, images and the systems that underpin them may be on the verge of collapse’.

In RUPTURE NO 6: biting the blowtorched peach, 2022, Phillipson proposes the gallery as alive and happening in a parallel time-zone. Described by the artist as a ‘whole new season’, the spaces are charged with colour, sound, and motion. Reimagining her 2020 Tate Britain Duveen Galleries commission, Phillipson conjures the room at Tate Liverpool as ‘a maladaptive ecosystem, an insistent atmosphere’. The mutated habitat and its title generate a proliferation of possibilities that resist coherence. Aggregates and agricultural technology interact with digital video, tinted light, and the sounds of howling animals. Motorised ships’ anchors become wind turbines, and gas canisters blow and clang. In Phillipson’s words, she is 'attempting to cultivate strangeness, and its potential to generate ecstatic experience.’

Phillipson’s multimedia projects include video, sculpture, installation, music, poetry, and digital media. She is, she says, ‘interested in the capacity of everything to resemble something else.’ She describes her works as ‘quantum thought experiments’. Plotting precise cognitive landscapes, they often carry a sense of latent threat – a suggestion that, as the artist puts it, ‘received ideas, images and the systems that underpin them may be on the verge of collapse.’

Veronica Ryan

Rather than having fixed meanings, Ryan’s work is typically open to a wide variety of readings, as implied by titles such as Multiple Conversations 2019–21 or Along a Spectrum 2021. The forms she creates sit between the familiar and unfamiliar, taking recognisable elements and materials – such as fruit, takeaway food containers, feathers, or paper – and reconfiguring them so as, in her own words to ‘talk about psychological resonance, about the extended self, and how we relate to objects that relate to us and the wider culture’.

She is inspired by information about herbs and plants inherited from her mother, describing this as an example of a ‘positive pathology’. The resulting plant-like sculptures are recurring motifs in Ryan’s work, recalling childhood memories as well as histories of global trade. Natural forms also bring to mind the climate emergency, particularly when they meet man-made detritus, such as packaging materials. These are suggestive of the ethics of individual waste, as well as the collective impact of humanity on the environment.

These environmental and ecological issues overlap with concerns around healing and recovery, highlighted by the inclusion of objects such as bandages and medical pillows, and brought into sharp focus by the Covid-19 pandemic. Such objects may bring to mind personal memories, but they also speak to wider systems of care. Ryan’s work invites us to consider the attachments we form with objects, materials, and places, highlighting the porosity between our inner lives and the world around us.

Sin Wai Kin

Using drag, Sin creates a multitude of characters who embody different themes and research. They exist across the spectrum of femininity and masculinity and reappear in different contexts, creating new constellations in the artists’ expanding universe.

The Storyteller appears first in Today’s Top Stories 2020 as an intergalactic news presenter. He reappears in It’s Always You 2021 as the more serious member of a four-piece boyband alongside The One (the class clown), Wai King (the heartthrob) and The Universe (the pretty boy). Here, the language of mainstream media is used to question the commodification of identity and queer coding within pop music, where polished personas contain promises of love, fantasy, and collective escape.

A Dream of Wholeness in Parts (2021) takes inspiration from Chuang Tzu’s ancient Taoist allegory Dream of the Butterfly. The text questions the nature of reality, as Chuang Tzu recounts a dream so vivid, that on waking up he questions whether he is actually a butterfly dreaming of being a man. In the film, Sin plays The Construct. This character is divided into two different aspects, as shown in their makeup, which is modelled on the fixed character roles of Peking and Cantonese opera. The Universe, from It’s Always You, also reappears here. Portraits of these characters emerge again via imprints made into facial wipes as the artist removed their makeup after a day’s filming. Sin uses these hybrid personas to subvert binaries of masculinity and femininity, self and other, thinking and feeling, life and death, dreaming and waking.

Ingrid Pollard

Pollard’s installation Seventeen of Sixty Eight 2018 has developed from decades of research into depictions of ‘the African’ on pub signs, their architecture, ephemera and surrounding landscapes. Through these materials, the artist highlights a strain of racism within British history that has been, and continues to be, hidden in plain sight. Pollard has said that ‘The signs reveal evidence of a multiplicity of meanings within the frames that echo a British history of colonial commerce, popular culture, portraiture and narrative’.

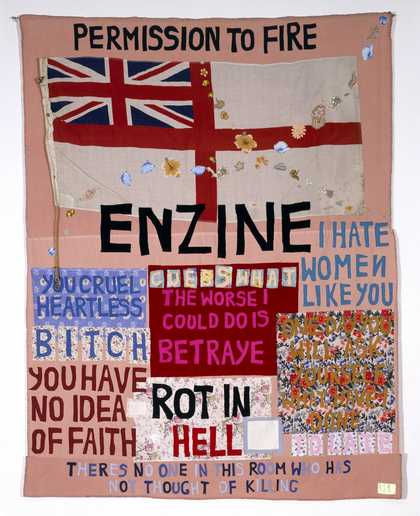

The photo series DENY: IMAGINE: ATTACK 1991 and SILENCE 2019 look at the language of power, both emotional and physical. Through these images, Pollard deals explicitly with a spectrum of medical, social, cultural, and historic homophobia and aggression.

Bow Down and Very Low – 123 2021 includes a trio of kinetic sculptures developed with artist Oliver Smart. Using everyday objects, these sculptures reference power dynamics though their gestures. With the sculptures’ repeated mechanical sound and movement, they seem to be deferential as well as threatening. The root of this figurative investigation is one particular moment and figure from a 1944 colonial propaganda film. This is shown in the lenticular images on display here, where we see a young Black girl who has been voted the ‘May Queen’. We could interpret her bow as a subservient gesture, or an acknowledgement and acceptance of her regal power.

Turner Prize 2022 was at Tate Liverpool, 20 October 2022 – 19 March 2023.