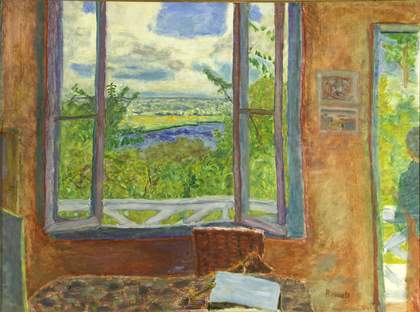

Pierre Bonnard Fenêtre ouverte sur la Seine (Vernon) 1911-12 Musée des Beaux-Arts (Nice, France)

Room 1

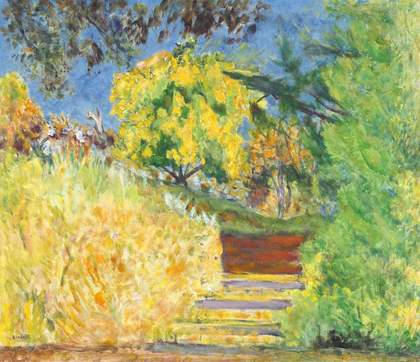

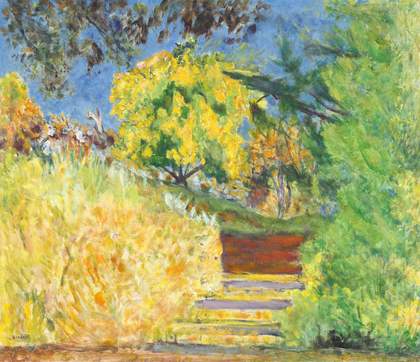

Pierre Bonnard Stairs in the Artist's Garden 1942-4 National Gallery of Art (Washington, USA)

‘I leave it… I come back… I do not let myself become absorbed by the object itself’.

The paintings of Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) create a remarkable sense of intimacy. Many of them allow glimpses into a private world, depicting the domestic life that Bonnard shared with his companion, Marthe de Méligny.

Although these works lovingly record the details of daily life, they do not simply transcribe what the artist saw. An initial moment of inspiration would be remembered, reflected upon, and reimagined as he composed his paintings in the studio. Rarely satisfied with his first effort, he often worked on each canvas over several months or even years.

Young Women in the Garden is one of the most extreme examples of a painting made over a long period of time. Having started work in 1921-3, Bonnard put the canvas aside for many years before revisiting and revising it in 1945-6. Resuming his work was part of an attempt to rediscover the original experience, bringing it into the present without losing its place in the past.

Beginning around 1900, this exhibition focuses on his mature work, as he developed a highly individual command of colour. Organised chronologically, it explores the presence of time and memory in Bonnard’s sensuous images of everyday life.

Room 2

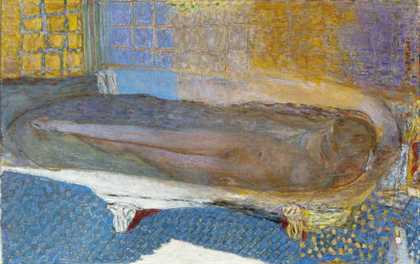

Pierre Bonnard Nu dans le bain 1936 Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris (Paris, France)

Defying convention, Pierre Bonnard and Marthe de Méligny lived as a couple for thirty years before marrying in 1925. These paintings from the first years of the twentieth century capture their intimate world.

In 1900 they had photographed each other naked in a summer garden, resembling a modern Adam and Eve. These informal snaps inspired some of Bonnard’s compositions. More generally, the practice of photography helped him to move away from the conventional poses of artists’ models.

His paintings of de Méligny capture incidental moments in the day, especially as she bathed and dressed. She sought treatment at spa towns and regularly took baths as a remedy for various illnesses. From unusual glimpses of her daily activities, Bonnard constructed an idealised vision of their life together that remained a key element of his work.

Room 3

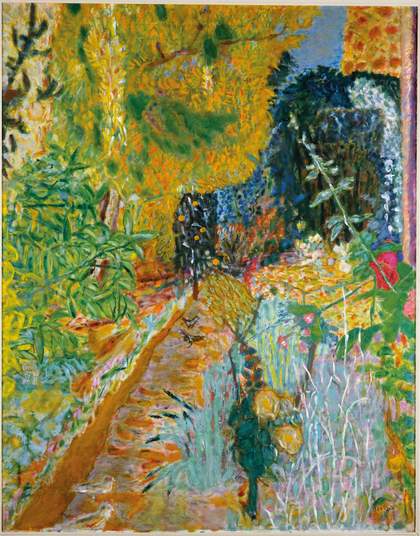

Pierre Bonnard

Coffee (1915)

Tate

‘Certainly colour had carried me away. I sacrificed form to it almost unconsciously.’

Around 1912, when he was already in his mid-forties, Bonnard altered the direction of his painting. His early success in the 1890s had been with decorative and fashionable work. Now he began to explore the possibilities of colour in an entirely individual way. Other artists of his generation, such as Henri Matisse, earned the nickname ‘fauves’ (wild beasts) for their use of raw colour. Bonnard took up the challenge, enriching his colour combinations.

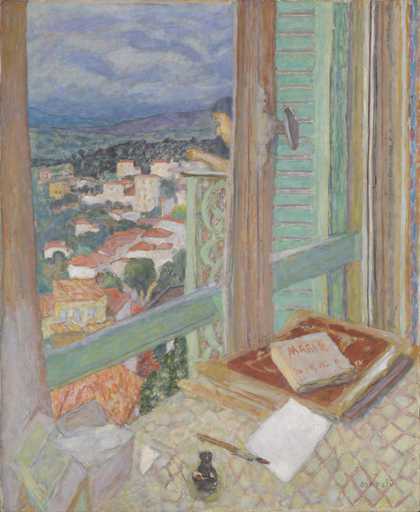

At the same time, he focused increasingly on landscape. Bonnard bought his first car in 1911, and made trips to explore the countryside around Paris. He regularly spent extended periods in southern France, and his paintings were infused with the powerful light that he experienced there. His mother’s home at Le Grand-Lemps in the Dauphiné, south-east France, was another favourite location. In 1912 he bought a small house at Vernonnet in Normandy which he called Ma Roulotte (My Caravan). The house and its surroundings immediately became subjects for his work.

Room 4

Pierre Bonnard

Pont de la Concorde (1913–15)

Tate

The First World War began in August 1914. In a matter of weeks, German forces reached the river Marne, within 30 miles of Paris. Bonnard and de Méligny were living in St-Germain-en-Laye, to the west of the city. The German advance brought the conflict within earshot.

At 46 years old, Bonnard was still eligible to serve in the French army, but continued to focus on his art. Although for the most part he painted his familiar subjects, a number of the works in this room show that he was not oblivious to the war. A Village in Ruins near Ham 1917 records the legacy of the terrible struggle along the Somme. Made around the same time, Summer 1917 may offer a vision of the peace that all hoped was to come

Room 5

Pierre Bonnard

The Bowl of Milk (c.1919)

Tate

For Bonnard, the early months of peace were marred by the death of his mother, Elizabeth, in March 1919. This loss signalled a larger break with the past. Her home in the Dauphiné had been a site of childhood holidays and extended family gatherings.

Bonnard’s painting became more subtle. Still engaged with the ‘photographic’ view of the snatched moment, he explored complex ways of composing and framing his vision. Familiar interiors and the everyday activities of reading and preparing meals were seen from fresh and surprising perspectives.

From his house in Vernonnet, Bonnard regularly visited Claude Monet at Giverny. Seeing the older Impressionist painter work on his large water-lily canvases seems to have invigorated Bonnard’s own landscape studies.

Room 6

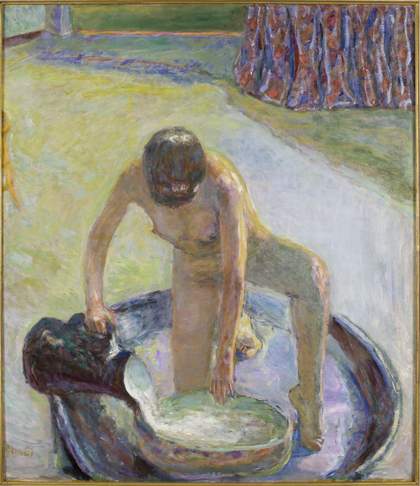

Pierre Bonnard Nude Crouching in the Tub 1918 Musée d'Orsay (Paris, France)

‘If one has in a sequence a simple colour as the point of departure, one composes the whole painting around it.’

In the early 1920s Bonnard used both new and familiar subjects to explore the possibilities of colour and composition. He was now increasingly away from Paris, but still exhibited there every year. Working independently of his contemporaries, he developed a more individual approach. He would go beyond natural appearances to intensify colour on the canvas, and set sharply contrasting colours alongside each other.

His house at Vernonnet was a constant source of inspiration. Many of the paintings he made there show the relationship between interior and exterior, man-made and natural environments. Each painting recorded subtle shifts in the fall of light, and used colour to bring different elements together.

During these years Bonnard’s relationship with de Méligny was threatened when he began a love affair with Renée Monchaty, who sometimes modelled for him. Bonnard and Monchaty visited Rome together in 1921, an experience that he recalled in the painting Piazza del Popolo, Rome 1922.

Room 7

Pierre Bonnard

The Window (1925)

Tate

Bonnard and de Méligny frequently travelled across France. They regularly spent summers at the house in Normandy and part of the winter in the south. They stayed at Arcachon on the Atlantic coast, and Deauville and other towns along the English Channel.

The subjects of Bonnard’s paintings were very varied. He drew inspiration from the places he visited, as well as views of and from his house in Normandy. As he moved, he took his paintings with him, continuing to work on them in different locations. This meant that the canvases developed as independent and self-contained entities. Whether addressing the domestic interior, still-life or landscape, Bonnard needed to summon the experience up in memory, making him acutely aware of the passage of time.

In 1923 Bonnard had proposed marriage to Renée Monchaty, but then broke off the engagement. He married de Méligny in August 1925. The following month Monchaty took her own life.

Room 8

Pierre Bonnard

The Table (1925)

Tate

The paintings in this room were all made in 1925. A number have been taken out of their frames in order to give a sense of how they appeared when Bonnard was working on them. He usually pinned his canvas directly on the wall, rather than using an artist’s easel. This had several advantages for him. His compositions could grow to fill the space of the canvas and he could work on several paintings side by side. It also allowed him to roll up his canvases and take them with him as he travelled around France.

Looking at the unframed pictures reveals that Bonnard painted very close to the edge of his piece of canvas. Sometimes he painted in a line around the edge to show where the frame would be. When, finally, the canvases were stretched and framed by his dealers Bernheim-Jeune, they were no longer part of Bonnard’s private world, and became objects entering the public realm.

Room 9

This room includes a selection of photographs which document Bonnard’s studio in the south of France. They include images by notable photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and André Ostier. Accompanying them is a range of archival material, including copies of the modernist art magazine Verve and extracts from interviews with the artist.

Together these materials offer a unique insight into Bonnard’s everyday surroundings, his working practices and his philosophical approach to painting.

Room 10

Pierre Bonnard

The Yellow Boat (c.1936–8)

Tate

In 1926 Bonnard and de Méligny purchased a modest house, in the village of Le Cannet, in the south of France. They named the house Le Bosquet (The Grove), due to the surrounding thicket of trees, and made a series of alterations to the property. Interior walls were knocked down to create a greater sense of space, and the windows were modified to let in more light. A studio was created in the north corner of the house, and a modern bathroom installed for de Méligny.

Bonnard continued to travel, maintaining a studio in Paris and spending portions of the summer in Normandy. From 1927, however, he spent increasing periods in the south. The southern climate had a significant impact on his work, flooding his paintings with warm light and rich shades of orange, red and yellow. Yet the raw scrutiny of his self-portraits suggests underlying anxieties and tensions.

Room 11

Pierre Bonnard

Nude in the Bath (1925)

Tate

‘The presence of the object … is a hindrance for the painter when he is painting.’

Bonnard held a major exhibition at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris in June 1933. At a time of economic slump, with political extremism gaining power across Europe, the colourful seduction of Bonnard’s work was seen as a message of hope. Critics passed over the more challenging aspects of his art to portray him as a ‘painter of happiness’. However, as Bonnard noted, ‘he who sings is not always happy’.

Marthe de Méligny continued to act as his principal subject. Her health was deteriorating and she would take baths every day, following the water treatment prescribed for her various ailments. Bonnard captures the intimacy and melancholy of their relationship in Nude in the Bath 1936, whose experimental use of colour suggests the distance of memory.