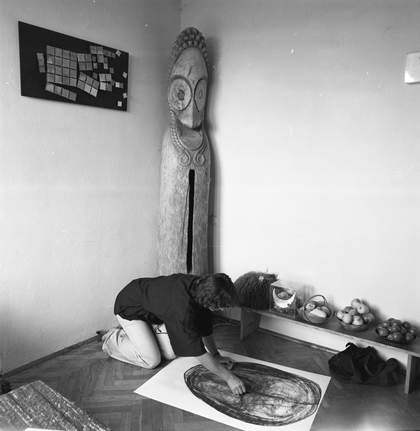

The artist at her loom, 1966. Artwork © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego. Photo © Jan Michalewski

In the 1960s and 70s Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930—2017) created large woven sculptures that became known as Abakans (after the artist’s surname). These ambiguous forms made from thread and rope defied categorisation and challenged the existing definitions of sculpture.

This exhibition surveys a transformative period of the artist’s early career when her weavings came off the wall into three-dimensional space. Abakanowicz first emerged as a leader of the New Tapestry movement of late 1960s Europe. Artists associated with the movement began to claim fibre as a valid medium for the creation of art. To this end, Abakanowicz saw importance in being recognised as a sculptor by major art galleries and museums. She exhibited internationally, bringing her monumental, fibrous forms into new relationships or ‘situations’ within the gallery – paving the way for the installation art of today.

Abakanowicz’s work also draws upon her childhood memories, including the traumas of the Second World War. Born into an aristocratic family of Tatar heritage whose circumstances declined over the course of the conflict, she was 15 years old when the war reached its conclusion. Later, living in Poland under the Communist regime, she dedicated herself fully to her career as an international artist. Abakanowicz brought natural fibres to the attention of the art world and developed an intensely personal artistic language. Her environmental attitudes, such as her wish to work and live in harmony with nature, feel particularly timely today.

Follow the development of Abakanowicz's artistic career by reading our illustrated timeline.

1. Beginnings

Following the Second World War, Abakanowicz pursued an education in painting and weaving, graduating from the Academy of Plastic Arts in Warsaw in 1954. This room shows the development of her work during the period that followed, from 1955 to 1965.

Censorship and restrictions of the arts in Poland enforced by the Soviet regime seemed to ease in the initial mid-1950s post-Stalinist thaw and trans-media experimentation flourished. Opportunities for ‘craft’ or ‘folk art’ were particularly well-supported through the state-sponsored Association of Polish Artists, of which Abakanowicz was a member. Although Abakanowicz experimented with pieces created for interior design and with painting on fabric, she was more interested in the expressive potential of weaving.

Living with her husband in a cramped one-room apartment, Abakanowicz used the studio looms of established artist and weaver Maria Laskiewicz (1891–1981) to produce large, experimental works. This improvisatory style of weaving without a ‘cartoon’ (template) shocked the critics when Abakanowicz first exhibited her work at the Lausanne Biennial of Tapestry in 1962. By 1965 however, she was presented with a gold medal for applied art at the São Paulo Biennial, using the prize money to buy a bigger apartment with a studio.

In this room, paintings of living organisms on draped fabric are presented alongside early weavings and industrial designs. The works carry the differing influences of Polish avant-garde developments in informel art (concerned with matter) and constructivism (concerned with spatial and geometric concepts).

2. Organic World

The artist in her home, 1981. Artwork © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz

Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News

Throughout her life, Abakanowicz maintained a strong connection to the natural world and the biological, organic matter of life. As she said: ‘I see fibre as the basic element constructing the organic world on our planet... It is from fibre that all living organisms are built, the tissue of plants, leaves and ourselves… our nerves, our genetic code, the canals of our veins, our muscles… We are fibrous structures.’

Weaving with sisal (the fibre from a flowering plant) and sometimes incorporating wool and horsehair, her textiles from the mid-1960s broke with the rectangular format of traditional tapestry and began to confront the viewer with curved forms hanging freely in space. Works from this period are brought together here, alongside objects, drawings and smaller pieces from throughout the artist’s career. Together, they demonstrate Abakanowicz’s lifelong preoccupation with the powerful energies of nature.

The artworks and objects shown in this room give an indication of the items Abakanowicz displayed within her home and studio. Animal horns, hides, shells, cocoons and other objects provided inspiration and were sometimes incorporated into work alongside plant and animal fibres . Her fascination with nature began as child, living in her grandfather’s seventeenth-century manor house deep in the Polish forest: ‘Strange powers dwelled in the woods and the lakes that belonged to my parents. Apparitions and inexplicable forces had their laws and their spaces…’.

3. Fibrous Forest

Baffled by the ambiguity of Abakanowicz’s work, in 1964 an art critic first coined the term ‘Abakans’, after the artist’s surname. Abakanowicz later adopted this term to refer to her large three-dimensional works, which she presented in dense arrangements. When installing an exhibition she determined their placement, often clustering works together in dialogue with each other and the surrounding gallery space.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Abakanowicz participated in an increasing number of international exhibitions. She referred to her installations as ‘situations’ and later as ‘environments’ into which she introduced found elements alongside her hand-woven forms. The artist was interested in the immersive possibilities of each arrangement in a particular space, lighting the artworks to produce dramatic shadows on the surrounding walls.

The works presented in the central space here are grouped together to echo some of Abakanowicz’s own installations. They also recall her interest in the forest’s ability to provide shelter. ‘The Abakans…’ she stated, ‘…were my escape from categories in art, they could not be classified. Larger than me, they were safe like the hollow trunk of the old willow I could enter as a child in search of hidden secrets.’

4. Petrified Organism

Red Rope, 1972. Edinburgh International Festival, Scotland (artist at centre). Artwork © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego. Photo © George A. Oliver [Glasgow]

In the 1970s, Abakanowicz began grouping her sculptures in new combinations for different exhibition spaces. The work shown here is a total ‘situation’ devised by the artist, combining a pair of giant garment-like, hanging forms that have been created from industrially woven cloth and ropes that spill out onto the floor. The hollow ‘garments’ evoke a protective shell or coat, while the entwined fibres of rope suggest the complexities of the nervous system.

Abakanowicz had begun to use the sisal from ropes to weave her works when other materials were less readily available. She explains how she sourced local materials and prepared them at home in Warsaw:, ‘Along the Vistula River one could find old, discarded ropes. They had their own history. They became my material. I pulled out thread, washed and dyed them on our gas stove.’

Rope later became an important element of her forms and environments. She would occasionally use it to lead the viewer between spaces or even to connect different buildings within a city. As she stated, ‘The rope to me is like a petrified organism, like a muscle devoid of activity. Moving it, changing its position and arrangement, touching it, I can learn its secrets and the multitude of its meanings… …It carries its own story within itself, it contributes this to its surroundings.’

5. Abakany

On the set of Abakany, 1970. Artwork © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego,

Photo © Barbara Stopczyk

In 1969 Abakanowicz collaborated with the avant-garde film director Jarosław Brzozowski (1911–69) and experimental composer Bogusław Schäffer (1929–2019) to create the film Abakany.

The strange, lunar or desert-like landscape is in fact the sand dunes of Slowiński National Park in Łeba on the Baltic coast of Poland. The artist planted her Abakans in the sand, supported by wooden armatures. The film captures the effect of the fibres blowing in the wind. Brozozowski died in the same year, and the film was completed by cinematographer Kazimierz Mucha (1923–2006) with indoor sequences showing Abakanowicz working in her studio and gallery space.

6. Invented Anatomy

The artist at work on Embryology, 1978-81 Artwork © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News

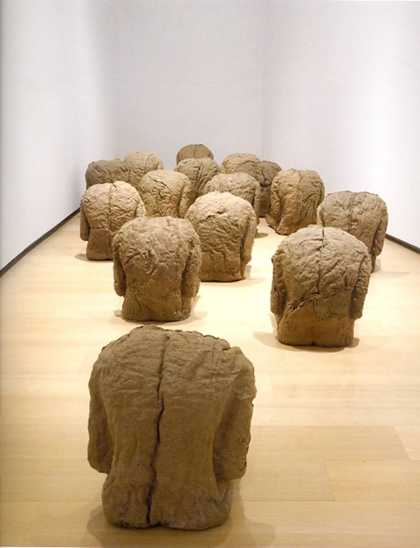

Frustrated at being labelled a fibre-artist, Abakanowicz began to use other materials in the 1980s, although she continued to use hessian and sisal to make increasingly figurative sculptures. In 1978 she made a new series of ambiguous forms titled Embryology, made from a combination of fabrics and fibres bundled and bound into rounded, organic masses. 800 of these forms were originally shown together at the Venice Biennale in 1980, when Abakanowicz was invited to exhibit in the Polish national pavilion. Referring to Embryology, she explained, ‘The contents, the inside, the interior of soft matter fascinated me… By ‘soft’, I meant organic, alive. What is organic? What makes it alive? In which region of throbbing begins the individuality of matter, its independent existence? …They were completing my physical need to create bellies, organs, an invented anatomy. Finally, a soft landscape of countless pieces related to each other.’

Embryology is both the title of a work and the description of a wider idea that Abakanowicz explored through her practice. Although Abakanowicz did not identify herself as a feminist, her woven sculptures have been seen by curators and writers as emblematic of powerful female imagery and art-making. Birth, life, vulnerability, and decay are suggested by forms that resemble nests, wombs and eggs.