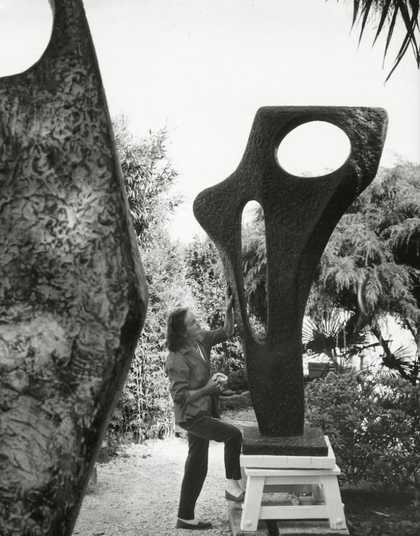

Barbara Hepworth with Figure (Archaean) 1959 in the garden of Trewyn Studio in 1961 © Bowness. Photograph by Rosemary Mathews

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) is one of the most influential British artists of the 20th century. She was at the forefront of international modern art, deeply spiritual, and passionately engaged with political and technological change. Born in Wakefield, Yorkshire, she moved to St Ives in 1939, where she lived and worked for the rest of her life. Her works reveal a singular vision of art and life, integrating her interests in music, dance, science, space exploration, politics, and religion, with personal events and experiences. This exhibition presents almost five decades of her sculptures, paintings, drawings, prints and designs.

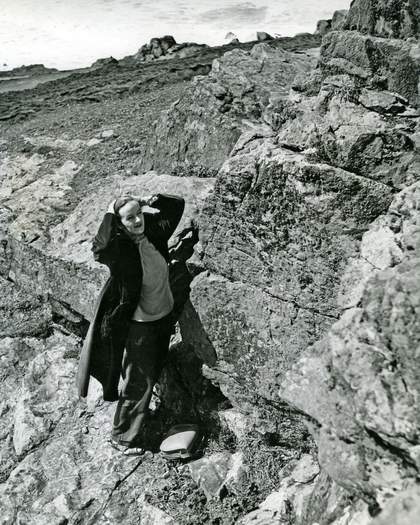

Hepworth expanded the possibilities for sculpture and art’s purpose within modern society. She continually returned to three important shapes in her work: ‘standing forms’, ‘two forms’ and ‘closed forms’. These iconic shapes are represented in this first exhibition room through works in wood, stone and bronze. Hepworth associated these forms with physical and emotional states, such as a figure poised at the top of a hill or a mother holding a child. Working in both abstraction and figuration, much of her art expresses our relationships with each other and our surroundings, and how art can reflect and alter our perceptions of the world.

Hepworth considered St Ives her ‘spiritual home’. Her former residence and workspace in the town, Trewyn Studio, is now the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden. Hepworth’s works – from drawings to monuments – are treasured in public and private collections and civic spaces worldwide. Celebrating her extraordinary life and achievements, Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life is organised by The Hepworth Wakefield in collaboration with the National Galleries of Scotland (Edinburgh) and Tate St Ives.

The forms which have had special meaning for me since childhood have been the standing form (which is the translation of my feeling towards the human being standing in landscape); the two forms (which is the tender relationship of one living thing beside another); and the closed form, such as the oval, spherical or pierced form (sometimes incorporating colour) which translates for me the association of meaning of gesture in landscape; in the repose of say a mother & child, or the feeling of the embrace of living things, either in nature or in the human spirit.

Hepworth 1970