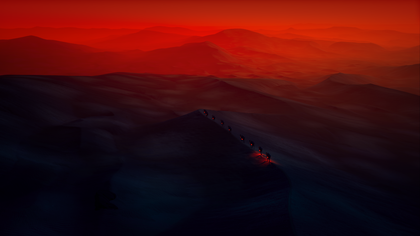

Cristina de Middel

Dhana (2012)

Tate

From hopeful utopias to bleak dystopias, speculative science fiction of space travel, technology and future worlds has long been a way of holding up a mirror to issues that we face in our current times.

Read on as we introduce seven artists who have been inspired by sci-fi to address some of the most pressing concerns today – including the climate crisis, settler-colonialism, capitalism and the gig economy, and Indigenous land rights.

Moon & Jeon

What is the role of art in an apocalypse? Artist duo Moon & Jeon try to answer this question in their film El Fin Del Mundo (The End of the World) – part of their News from Nowhere series. They imagine the lives of two artists working side by side across two timelines: one during the apocalypse, the other in the post-apocalyptic, high-tech world.

While the catastrophe in the film is imaginary, Moon & Jeon are heavily inspired by real issues like climate change, rampant capitalism (particularly in the art world) and historic events like the Korean War.

By blurring the lines between reality and fiction, the vision of the future that they present is intended as a new way of understanding and addressing what is happening in the present:

We love the scientific way to rethink about our present time. Frankly speaking, we’re not interested in the future. We’re interested in the present time. Because the future is a mirror of the present.

Joonho Jeo

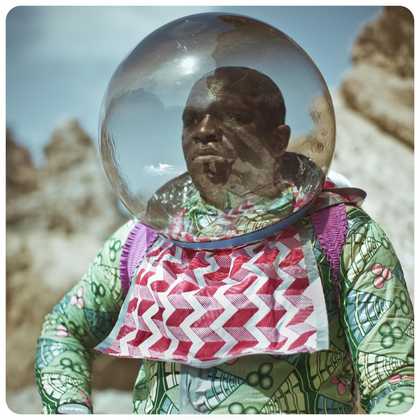

Cristina de Middel

24 October 1964 was the day that science teacher Edward Makuka Nkoloso planned to launch a teenage girl, a Christian missionary and two cats into space in a copper rocket.

This (unofficial) expedition – which hoped to put the first African astronaut on the moon – never took off.

Cristina de Middel

Mbulumbublu (2012)

Tate

Cristina de Middel

Ifulegi (2012)

Tate

Nearly 50 years later, photographer Cristina de Middel presented her imagined vision of these events in her photobook The Afronauts. Disillusioned with her career in photojournalism, she took the supposed rules of the trade – truthfulness, accuracy and no manipulation – and purposely created the opposite:

I put together a bunch of the visual clichés of Africa, like the costumes, the textiles, the typically African witchcraft imagery, and so on—all of the things that you find on Google when you type in ‘Africa’—and mixed them with all of the types of things that you find on Google when you type in ‘space’… I put all of these things together, I shook them up, and ended up with The Afronauts.

Cristina de Middel

De Middel believes the West still has a “postcolonial vision” of Africa, which hinders the way it could be supporting the continent’s future development. The Afronauts’ mix of historical events and fantasy makes us actively question where our outdated ideas begin and end.

Ayman Zedani

Ayman Zedani The Desert Keepers, 2022. Photo: Artur Weber; Courtesy of the artist

Artist Ayman Zedani studies the survival strategies of plants in the Gulf region, where he lives and works. He hopes they might unveil ideas on how we could collectively survive under the looming threat of the climate crisis.

His video installation The Desert Keepers (2022) shines a light on how some plants in the Arabian desert take the genes from other plants, and pass them on to their offspring, to maximise the species’ future chance of survival.

Plants are just one of the many “non-human protagonists” that Zedani champions in his art. Others have included bacteria, yeast and larger organisms like camels. “It’s really important to put forward new characters, new icons and new stories that will make us think about the liveability of the future,” he says, in order to show that we are all connected:

I find it interesting how people perceive nature as a separate thing from us in a sense. The fact is, we are an expression of nature itself. So whatever we’re doing is basically part of nature. For me, nature is everything.

Ayman Zedani

He describes another video, Earthseed (2021), as weaving together “factual information with fictional narrative” to emphasise the potential effect of climate change, in hopes of inspiring collaborative action across viewers in the Gulf and beyond.

Ayoung Kim

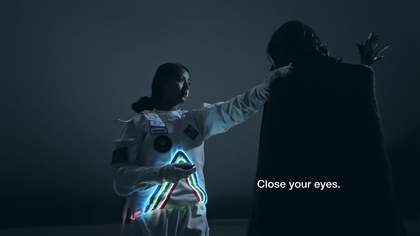

Ayoung Kim

Delivery Dancer’s Sphere (2022)

Tate

Ernst Mo makes deliveries on her motorcycle at the speed of light.

She is a Ghost Dancer – a top-ranking driver for the fictional company Delivery Dancer – in Ayoung Kim’s video artwork Delivery Dancer’s Sphere. But when Ernst crosses paths with her doppelgänger from another world, En Storm, time slows down, deliveries are late, and her top rank becomes at risk…

The idea behind Delivery Dancer’s Sphere came to Kim during the pandemic: under lockdown in Seoul, she used food delivery apps almost daily for three years yet never once met her riders. She imagined their life in a precarious, gig-economy job, where speed and optimisation mattered above all else, and took the idea to its extreme.

Mixing quantum theory into the story, the doppelgänger character En Storm represents a different world – suggesting the possibility that we could change our own world. “I’ve always been interested in those people who are deviating from the solid logic of our society and who have subversive power, who can change the world a little bit,” says Kim.

Shu Lea Cheang

How do we present ancient Indigenous culture in this techno era?

Shu Lea Cheang

A hunter falls asleep inside a hollow tree while she shelters from the rain. In her dreams, she meets a group of gender non-binary spirit beings called Hagay, who pass on to her their ancestral knowledge of weaving, hunting and living.

This folklore from Taiwan’s Indigenous Truku tribe is the basis of Hagay Dreaming, a performance piece by new media artist Shu Lea Cheang and Truku artist and practicing shaman Dondon Hounwn, which combines Truku tribal dance and rituals with cutting-edge lighting, lasers, film and installation. Its artistic vision is based on the Truku people’s principle of living, Gaya, where all living beings are connected in a state of total trust.

Hagay Dreaming. Photo credit: Hsuan Lang Lin (林軒朗)

Cheang is no stranger to working with the latest technology – from video and audio to electronics and internet art – as well as sci-fi themes (she has dubbed her four feature films as ‘sci-fi new queer cinema’). But for her, Hagay Dreaming is as much about looking back as forward: having worked for decades in Europe and the US, the piece is a way of reconnecting with her homeland and its Indigenous culture. Hagay Dreaming is a return to Taiwan’s earliest years (“in our tribal societies there was no binary gender perception”) – before the country was changed by Christianity, Japan and Mainland China – to pass on this Indigenous knowledge to future generations.

Larissa Sansour

Early in her career, artist Larissa Sansour thought truth was enough to sway political dialogue – in particular about Palestine, where she grew up. She later realised the importance of narrative in reclaiming marginalised histories and experiences.

The idea was that unmasking the realities on the ground would eventually influence the political dialogue. Yet somehow all it did was generate the illusion of progress. Feeding the dialogue became a way of maintaining the status quo.

Larissa Sansour

After abandoning her original documentary-driven approach, “I eventually found the conceptual distance I was seeking in science fiction,” she said. “The shift of context made the discipline a philosophical playground in which new meaning could arise."

Her film In Vitro takes subjects affecting Palestinians, such as identity, belonging and collective trauma, and transposes them to a fictional world after an eco-catastrophe. Two characters living in an underground bunker – one, a scientist who longs for humanity to return above ground and the other, a clone who has only known the post-apocalyptic world – argue over what should be preserved, and let go of, as they try to move forward in the aftermath of the disaster.

As the film questions the importance of identity within this fictional eco-disaster, it also challenges – in the real world – to what extent nationalism is important within larger issues such as climate change. “Ambitions for a nation-state seem oddly anachronistic in the face of a global climate catastrophe. Yet, across the globe, the language of nationalism appears stronger than ever,” she muses. Working in sci-fi allows Sansour to tell stories from a personal, collective and even global perspective – in ways outside of established narratives.

Subash Thebe Limbu

Adivasi Futurism could be a domain for imagining futures that we currently assume as impossible.

Subash Thebe Limbu

Subash Thebe Limbu, Ladhamba Tayem; Future Continuous, 2023. Commissioned by VH AWARD of Hyundai Motor Group. © Subash Thebe Limbu, courtesy of the artist

Artist Subash Thebe Limbu was inspired to develop his concept of Adivasi Futurism after exploring Afrofuturism – particularly the works of Black sci-fi writer Octavia Butler – and Indigenous Futurism. Both genres use science, technology and fiction to imagine futures where oppressed communities are liberated and thriving under their own sovereignty. ‘Adivasi’ is the Nepalese word for ‘Indigenous’ but can also be applied for the wider Indigenous population in the Indian subcontinent.

Many of his films explore the future coming face-to-face with the past: Ladhamba Tayem; Future Continuous from 2023 imagines a conversation between a real 18th century Yakthung (the Indigenous people in present Eastern Nepal) freedom fighter and a fictional Yakthung time-traveller from the future.

The two characters from the same community, living eons apart, are woven into each other’s timelines as a reminder to each other of past events and potential futures. Here, Limbu nods to the Adivasi belief that time is not rigid but, rather, non-linear and malleable. It also raises a question to the viewer: where do you stand within this timeline, and how would history look back on your actions, past, present and future?

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor