Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8 (Tate T14882) by Eleanor Antin is, in a sense, a group portrait, in that it represents one hundred named ‘sitters’ – the poets mentioned in the title. The work depicts not merely a collection of individuals, however; it also represents a snapshot of a particular milieu: the 1960s New York poetry and performance scene. The box offers a glimpse of the creative circles in which Eleanor Antin and her husband David moved in the years leading up to their relocation to California in 1968. The information that it presents is at once personal (a record of those individuals with whom Antin came into contact over the course of three years) and historical (a record of those poets active in New York during that period).

Shaping the scene

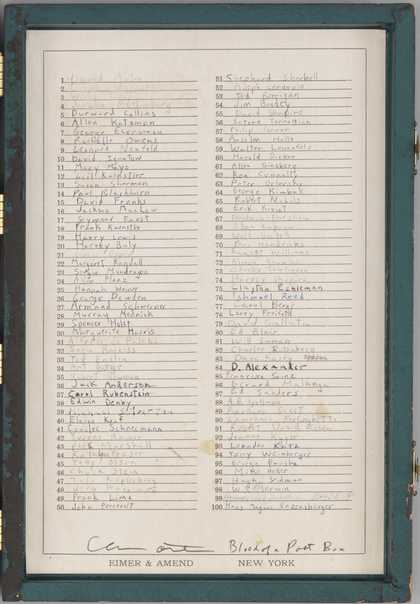

Fig.1

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8, detail of the list of poets pasted onto the inside of the lid

Tate T14882

© Eleanor Antin

Photo © Tate

The names in Blood of a Poet Box represent key figures in the history of poetry and art in America during the post-war decades (fig.1). Many of them were well known, albeit in avant-garde circles, by the time Antin made her box. Their work appeared regularly in such publications as Evergreen Review, Black Mountain Review, Origin and other little magazines and literary journals. Among the people represented in Antin’s box are several that founded and edited their own literary journals: Ted Berrigan, founder-editor of C magazine; Jim Brodey, who published the magazine Clothesline in 1965 and 1970; Margaret Randall, founder and co-editor of the bilingual quarterly El Corno Emplumado/The Plumed Horn; Ishmael Reed, who co-founded the countercultural newspaper the East Village Other in 1965; Ed Sanders, founder of Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts and its associated press; and Clayton Eshleman, founder of the literary review Caterpillar. Several of these published David Antin’s poetry and criticism. Antin himself edited the magazine Some/thing between 1965 and 1970 and may well have facilitated his wife’s access to several of these figures. This litany of underground editors and publishers hints at the cultural and literary networks that the box implies, even beyond those one hundred names that it includes. It also demonstrates that those poets Antin chose were among the key figures shaping the scene as it developed.

A number of Antin’s subjects – Paul Blackburn, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Barbara Guest and Peter Orlovsky – belonged to the generation of writers made known by Donald Allen’s influential 1960 anthology The New American Poetry, 1945–1960, which had been published in New York by Grove Press.1 Others, such as Diane Wakoski and Sotère Torregian, appeared in Paul Carroll’s equally influential anthology The Young American Poets, published in 1968 by Big Table in Chicago.2 But the poetry scene that was centred on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in reality blurred the generational and geographical distinctions that these anthologies sought to delineate. If Blood of a Poet Box questions the nature of identity, then it also questions the idea of a ‘school’ of New York Poets, the label coined by Allen to designate a grouping based on both aesthetic similarities and what literary scholar Terence Diggory has called ‘intimate community’;3 that is, the close professional and personal connections that facilitated and shaped the scene.

The poets included in Antin’s box do not represent a single school, but hail from a variety of literary backgrounds, traditions and approaches, pointing to the fluid nature of overlapping communities of writers and artists. Although many collaborative relationships are represented, they were not necessarily all known to each other. The poets that Antin included are associated with distinct but intersecting groupings including the Black Mountain poets (Anselm Hollo, Paul Blackburn), the New York School’s first and second generations (Barbara Guest, Ted Berrigan, Jim Brodey, Joseph Ceravolo), Deep Image poets (Jerome Rothenberg), Process poets (Jackson Mac Low) and the Beats (Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Joanne Kyger). Although seen as distinct in their approaches, they were united by an anti-academic approach, a self-conscious response to the modernist poetics of writers such as Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams and participation in the live poetry events that epitomised this small avant-garde community.

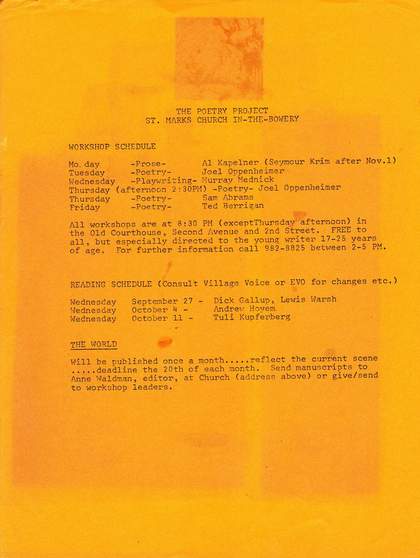

Fig.2

Flyer for the workshop and poetry reading schedule at the Poetry Project, St Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, New York, 1967

Antin’s litany illustrates the poetry networks that spanned both coasts of the United States as well as including the occasional European; it also evokes the cultural fulcrum that existed in particular neighbourhoods during the 1960s. These poets were to be found in the alternative spaces of creation and performance that characterised the New York art, poetry and performance scene in the 1960s, centred on Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side. Poetry readings were held in jazz clubs, bookshops and coffeehouses, including the Five Spot Café jazz club, the Tenth Street Coffeehouse, Les Deux Mégots, Café Le Metro and, later, the Poetry Project founded by Paul Blackburn at St Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. The pasted list of poets inside the lid of Blood of a Poet Box is reminiscent of printed flyers that these venues used to advertise their line-up, which depended on the recognisability of key names (fig.2). These were intimate venues that attracted small but regular audiences often comprised of fellow poets and artists. According to historian and critic Sally Banes’s account of Greenwich Village in the early 1960s, these alternative spaces were characterised by an aura of offbeat domesticity and a folksy atmosphere derived from their small scale and intimate nature.4 They also represented a collective mode of cultural production and an important social network for the underground scene.

A creative community

Fig.3

James Gossage

Caffe Cino, New York, July 1965

© James Gossage

The Antins lived for a time on Cornelia Street in Greenwich Village, across the street from Caffe Cino (fig.3), an establishment opened in 1958 that, from 1960 onwards, hosted poetry readings on Tuesday evenings. They were organised by George Economou, who makes an appearance in Blood of a Poet Box as Eleanor Antin’s seventh poet.5 David Antin was among those who read their poetry at Caffe Cino, as did others who are included in the box, such as Jerome Rothenberg, Rochelle Owens, Paul Blackburn and Clayton Eshleman. The Cino would also become known as a home of experimental performance and theatre; in 1964, it was the venue for a performance of Yvonne Rainer and Larry Loonin’s Incidents (fig.4). In its inclusion of performance in various guises, be it identified with poetry, theatre or visual art, the Cino was typical of alternative spaces in New York during this period.6 Coffeehouses defined an alternative cultural scene in their embrace of live poetry and their foray into experimental theatre. By virtue of the censure they received from the city’s licensing authorities, which regularly cited Village coffeehouses as breaching fire regulations and codes of use that forbade public entertainment, they also posed a more direct challenge to authority.7

Fig.4

Yvonne Rainer and Robert Dahdah moving the furniture at Caffe Cino as part of Rainer and Larry Loonin’s performance of Incidents, June 1964

Photo: Robert Patrick

Coffeehouses such as Caffe Cino belonged to an emerging off-off-Broadway theatre scene that also flourished in dedicated venues including Café La MaMa, The Living Theatre, the New York Poets Theatre and Judson Memorial Church, which staged experimental theatre performances and multi-media happenings. These were the kinds of events that writer Susan Sontag described in 1962 as ‘a new, and still esoteric genre of spectacle’ performed in ‘lofts, small art galleries, backyards, and small theatre before an audience averaging between thirty and one hundred persons’.8 Exhilarated reports of these events were published in the pages of the newspaper the Village Voice, shoring up the neighbourhood’s Bohemian reputation, even as it developed from Beat to hippie culture during the 1960s. The Voice’s art critic from 1966 to 1974, John Perrault, authored many of these reviews and is also included in Antin’s box.9

Historian Daniel Kane has described the Lower East Side poetry scene, which overlapped with that centred on Greenwich Village, as a microcosm of a broader countercultural interest in community building as an alternative and dissident practice. He notes that ‘poetry as a communal effort parallels community-building work typical of the 1960s and changes established notions of what constitutes authorship and literary production’.10 The poetry scene privileged poetry in performance, placing emphasis both on the aural qualities of the written word and on the process of communion with a live audience: reading aloud was a crucial form of sociability and community forging. Kane’s description might be applied equally to works being made in the visual arts at the same time, particularly in the context of the burgeoning happenings movement, in which audience participation was integral to the creation of the work, and the experimental theatre being produced by radical companies such as The Living Theatre and Bread and Puppet Theater. Although not performance per se, Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box similarly aligns with Kane’s description in its integration of, and reliance on, this participatory community comprised of contributors who might be considered authors as much as subjects.

Antin’s choice to represent her subjects via the intimate act of blood-giving points to a sort of familial bond and it is important to note that Antin was very much a part of this group. In many ways the poetry and performance scene in 1960s New York was a close-knit community that stood in as an alternative urban family. The poet Joel Lewis’s description of that scene suggests an introspective coterie, in which each member depended on the others to further artistic endeavours and careers alike: ‘in the end’, he wrote, ‘it is poets reading to other poets and then participating in the underground economy of talking and writing that established a poet’s position within the active literary culture.’11 As the list of names in Blood of a Poet Box indicates, Antin, too, participated in this ‘underground economy’; the poets and performers she encountered in this milieu were often familiar to her and provided both inspiration and subject matter. Indeed, the Antins had in the early 1960s attempted to live outside New York City in a quiet town in Sullivan County, a move that David Antin later described as misguided: Eleanor ‘didn’t need quiet’, he wrote, ‘she needed the art scene. So [in 1963] we came back to the city.’12

In fact, while Blood of a Poet Box echoes this sense of community in its quasi-collaborative production, Antin’s decision to create an artwork out of her encounters in these poetry clubs stemmed in part from a sense of frustration with what she saw as the sometimes interminable poetry readings: ‘I began collecting the blood specimens because some of those readings went on all night and groups of us were half asleep sitting along the walls,’ she has explained. ‘So I figured I should do an artwork instead of getting drunk and being bored.’13 Although somewhat tongue-in-cheek, Antin’s comment points not only to the nature of the events – long and not always scintillating – but also to the frustration that she already felt with poetry itself and a desire to move into a different form of artistic expression.

Participation and omission

The names in Blood of a Poet Box represent the close-knit nature of the social and creative circles in which the Antins moved. Although several close friends of hers and her husband’s are among Antin’s subjects, many others are acquaintances, included in the project as they visited or passed through New York City. Among the former is Diane Wakoski, whom the Antins had known for some years, and who would memorialise Antin’s project in verse form in ‘A Long Poem for Eleanor Who Collects the Blood of Poets’ (1965), a typescript of which remains among Antin’s papers.14 Among the latter were the likes of British poet and translator Charles Tomlinson, whose sample was collected while he was visiting the city, and who remained an outsider observer of the scene rather than a participant.

The circle that Blood of a Poet Box represents is formed as much by those who declined or were missed as by those who accepted Antin’s invitation, particularly since Antin tends to narrate each of these encounters in accounts of making the work. The poet John Ashbery was apparently reluctant to part with his blood.15 So, too, was the New York poet and curator Frank O’Hara: according to Antin’s recollection in 2009, ‘O’Hara in his usual insouciant way said, “Sperm yes, blood no.” I said, “Sorry, I don’t want your sperm.” Too bad because I liked Frank.’16 A chance for Antin to obtain the blood of renowned Chilean poet Pablo Neruda at a dinner engagement in Brooklyn Heights was missed due to David Antin’s hesitation at imposing on such an acclaimed elder figure, a decision that Eleanor Antin still regrets and one that hints at the hierarchies evident even within the avant-garde scene.17 These missed opportunities notwithstanding, there were several famous names among Antin’s poets, including Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg.

Fig.5

Carolee Schneemann

Meat Joy 1964

Group kinetic theatre performance including raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, plastic, rope, shredded scrap paper

© Carolee Schneemann

As the project developed, Antin cast her net more broadly. As a result, the box features a number of figures known predominantly not for their work writing poems, but for accomplishments in other fields. These include Carolee Schneemann, Yvonne Rainer, Philip Corner, Allan Kaprow and Alison Knowles, who were linked variously with happenings, Fluxus and other experimental music, dance and performance art practices that emerged and flourished in 1960s New York. A painter and dancer, Schneemann was well know for her kinetic theatre by the time she participated in Antin’s project, with works such as Meat Joy 1964 (fig.5), which featured in the second issue of Some/thing, edited by David Antin. Dancer and choreographer Rainer was associated with Judson Dance Theater, the Greenwich Village company based at the Judson Memorial Church in Washington Square. Corner was a composer who also participated in performance events and was a founder-member of Fluxus; Kaprow had become known as the father of New York happenings by virtue of the immersive and interactive works that he produced from the late 1950s, such as 18 Happenings in 6 Parts at the Reuben Gallery in 1959 and Apple Shrine at the Judson Gallery in 1960. Artist Alison Knowles was associated with both happenings and Fluxus and known for her performances, installations and artist books, including the Fluxus event score #2 Proposition (Make a Salad) 1962.18 In a manner similar to the communities of poets, many of these individuals’ experimental music and performance works were created for and disseminated among a small community of kindred spirits, via instructional scores in small presses and intimate events in galleries, off-off-Broadway theatres and other venues and locations.

Antin’s inclusion of these visual, musical and performance artists reflected the close relationship between those operating across various disciplines during this period, one in which poets worked hand in hand with artists, performers, dancers and composers. It put under pressure the designation ‘poet’, which in Antin’s hands expanded to embrace those whom she considered poetic ‘types’, even though the works they produced might not typically be regarded as poems. Antin has explained that she views her expansive approach as indicative of the period in which she matured creatively. ‘When I was a kid,’ she has said, ‘I didn’t know what kind of artist I was. I knew I was an artist, I just didn’t know if I was an actor, I didn’t know if I was a writer, I didn’t even know if I was a painter. I was fortunate that I grew up as an artist in a time when all the barriers were falling down.’19 Indeed, she was not the only artist concerned with breaking down the traditional boundaries between disciplines during this period. Schneemann, for example, continued to consider herself a painter long after her work had developed into three dimensions and included ephemeral performance.20 Against the backdrop of the social upheaval of the 1960s, artists and poets presented a challenge to the conventional classificatory systems of high art, opting instead to create work that could be termed multi-media, intermedia or ‘mixed means’.

In his 1968 study The Theater of Mixed Means, the poet and critic Richard Kostelanetz charted a range of artistic outputs that adopted environmental and kinetic elements drawn from theatre, music and performance poetry.21 In many ways, Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box fits within this category. Although it seems most closely associated with sculpture in its three-dimensionality and with conceptual art in its emphasis on task-driven process, the work also contains an element of theatricality and ritual, and an emphasis on bodily presence that aligns it with performance. Indeed, it might be claimed that the encounters, negotiations and actions of collecting blood that the work necessitated can be considered as much a part of the work as the finished product. In this way, it anticipated the performative elements of Antin’s later approach, which moved increasingly towards works that engaged with masquerade, performance and narrative, such as The King of Solana Beach 1972–5 or the Antinova project, which began in the late 1970s.

Antin has also linked her expansive definition of the term ‘poet’ to her desire to include more women in the work, citing the examples of Rainer and Schneemann in particular.22 The community delineated by Blood of a Poet Box is predominantly male (only twenty of the one hundred subjects are women). In this, it reflects the nature of the New York scene at the time, in which, Antin recalls, there were few women reading their work in public, despite the stated aims of many of its key figures to challenge established social norms.23 Although the work does not confront identity politics head on, the demographic of its sitters points to the relatively narrow social makeup of the New York avant-garde, despite its claims to bohemianism. Blood of a Poet Box is at once a group portrait, a portrait of a particular underground scene, and an attempt to reconcile the contradictions inherent within that milieu.

‘The most communal activity in the world’

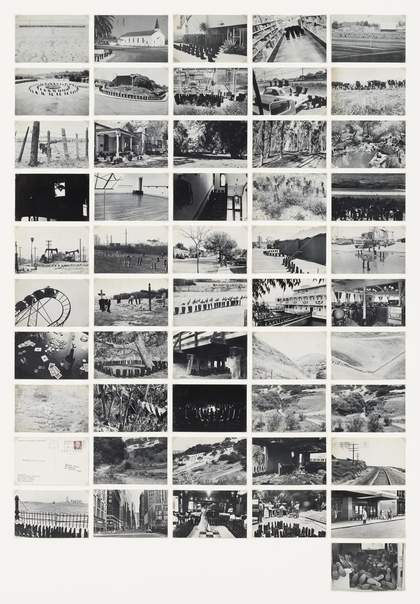

Fig.6

Eleanor Antin

100 Boots 1971–3

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Eleanor Antin

This essay has thus far presented the poets listed in Blood of a Poet Box as subjects or sitters, but they might also be considered as collaborators in the production of the work to a certain extent. In this guise, their inclusion is an early indication of Antin’s understanding of art as ‘the most communal activity in the world’.24 Schneemann describes the creative process that the box involved in similar terms, as a collaboration in which the poet participants ‘offered their essence’ both literally and figuratively.25 Accordingly, Antin’s project was conceived as a kind of implicit contract of understanding at a time when many artists were investigating and challenging the relationship between artist and audience. The act of collecting blood paralleled a move in happenings and immersive installation environments towards redefining the audience, shifting them from passive spectators to active participants. In the process of making Blood of a Poet Box, Antin herself was transformed from passive audience member in a poetry venue to active solicitor of blood samples. Her subjects were also transformed by means of their physical and social participation in her artwork. Antin would adopt a similar strategy of implicating friends and peers in the creative process in later works, such as 100 Boots 1971–3 (fig.6), in which she mailed postcards to around one thousand ‘artists, dancers, writers, musicians, critics, museums, galleries, universities, libraries, and assorted innocent bystanders’.26 She would not, however, ask participants again for such a personal donation in the name of art.

Blood of a Poet Box took around three years to complete and Antin has recalled that she felt a sense of relief when all one hundred slots were filled.27 Shortly after the work was finished, the Antins moved to California where they took up jobs at the University of California at Irvine and at San Diego. Antin has described the period as one of change not only on a personal level but also in terms of the New York art scene: the heyday of Judson Theater was over, in Antin’s judgment; she viewed both minimalism and pop art as on the wane, too.28 The completion of Blood of a Poet Box thus marked a turning point in her career and memorialised a particular time, place and community.