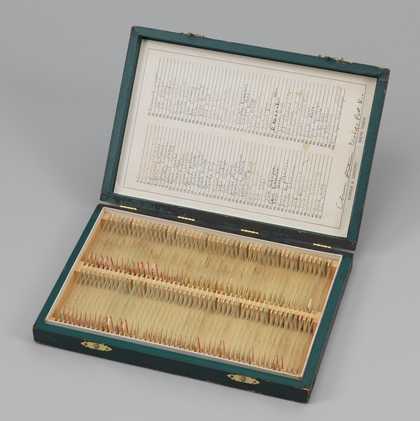

Fig.1

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8

Wood, cardboard, glass slides, blood, brass, paper and ink

Displayed: 28 x 290 x 405 mm

Tate T14882

© Eleanor Antin

Photo © Tate

If Eleanor Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8 (Tate T14882; fig.1) is a group portrait of sorts, then it embodies an unconventional take on a conventional genre. It does not depict a naturalistic or physiognomic likeness of its sitters, nor does it seem clearly to point to an idealised set of attributes via recognisable iconographic codes.1 Instead, Blood of a Poet Box operates as a conceptual portrait that is as much about the genre of representation as it is about conveying details about particular individuals. In the twentieth century, in the wake of conceptual art, ‘the status of naturalistic portraiture as a progressive form of elite art has been seriously undermined’, as art historian Joanna Woodall notes.2 For many artists, Antin included, this involved expanding the terms of portraiture to include previously excluded modes and materials and a non-mimetic, conceptual or symbolic approach to representing a subject.3 While Antin’s work certainly appears distinct from the centuries-long conventions of portraiture as a genre associated with elite art patronage and the construction and assertion of positions of power, Blood of a Poet Box appears to tread an ambivalent line in relation to these traditions. This essay considers the ways in which Antin has drawn on the traditions of art and art history in very deliberate ways, and contextualises this approach with respect to other practices often described under the term postmodernism.

Blood of a Poet Box as portrait

Portraiture was treated as a problematic genre in much twentieth-century art. Against the backdrop of radical identity politics that sought to deconstruct social and cultural hierarchies, many artists questioned the way in which images and image-making constructed subjects in line with those hierarchies. For some, this interrogation of representation entailed an outright rejection of traditional art; but for others, like Antin, it provided ripe material for questioning established assumptions about both art and identity.

To what extent does Blood of a Poet Box engage with the history and conventions of portrait depiction? Certainly, it does not resemble a traditional portrait. However, there are similarities: the genre of portraiture historically had much to do with asserting genealogy and bloodline. In this regard, Antin’s box might be seen to allude to artistic traditions that were well established in the early modern period in particular, in which a portrait served as a declaration of status via material possessions, familial lineage and symbols of political and economic status. The image thus enacted what literary scholar Wendy Steiner has described as ‘a complicated history of associations between appearance and character’, in which the implication is given that an apparently faithful representation will offer insight into a sitter’s personal traits and attributes.4 Antin’s work refutes these assumptions, instead presenting an alternative relationship between sitter and representation.

Blood of a Poet Box rejects naturalistic representation, setting it apart from conventional portraiture. Yet it retains an element of realism by means of its use of blood as a medium. This strategy might lay claim to authenticity and accuracy on the grounds that while a sitter can craft a false self-image through self-presentation, their drop of blood acts somehow as ‘evidence’. Blood of a Poet Box is not a representation of its sitters; rather it presents a part of them. Art historian Richard Brilliant has observed that the idea of ‘likeness’ upon which portraiture is predicated ‘presupposes some degree of difference between the things compared, otherwise they would be identical and no question of likeness would arise’.5 If a traditional portrait operates in the realm of allegory, according to which one thing represents another, then in Antin’s work the link between the sitter and their representation is indexical, carried out at the level of the body and its residues.

In Antin’s hands, however, blood is revealed to be a complicated and unreliable signifier of identity. Despite the direct biological link, what is promised in this portrait is not a coherent and complete picture of the sitter such as would be expected in historical portraits, but only a fragment. The information that this trace offers up is only partial; the viewer remains in the dark. Blood of a Poet Box thus shatters any illusion of objectivity that blood samples might promise as well as laying bare the mechanisms by which a portrait claims to reproduce an authentic self.

Portraiture in Antin’s practice

Fig.2

Eleanor Antin

Jeanie 1969 from the series California Lives

Collection of the artist

© Eleanor Antin

Fig.3

Eleanor Antin

Yvonne Rainer 1970 from the series Portraits of Eight New York Women

Collection of the artist

© Eleanor Antin

The politics and strategies of portraiture would remain an ongoing concern for Antin as she cemented her status as a visual artist. Blood of a Poet Box is the earliest manifestation of this interest, which Antin would develop in further series of artworks during the subsequent decade. For example, in her two series of ‘consumer portraits’ – California Lives 1969, exhibited at John Newman’s Gain Ground Gallery in New York in 1970, and Portraits of Eight New York Women 1970, first exhibited at the Chelsea Hotel, also in New York – Antin created alternative portraits of fictional individuals and art world friends respectively, via assemblages and tableaux made from consumer goods. For example, Jeanie from the California Lives series comprises a TV tray and stand, a melamine cup and saucer, a filter-tip cigarette, a single pink hair curler, and a matchbook from George’s Steak and Lobster House (fig.2). Yvonne Rainer from Portraits of Eight New York Women comprises an exercise bike with a horn and plastic basket, a grey sweatshirt, a mirror and a bunch of artificial roses (fig.3). The critic Lawrence Alloway, in a review of the Gain Ground exhibition published in the Nation, described the playful way in which the California Lives series used objects as stand-ins for people. The works were, he wrote, ‘tokens of the human presence’ and ‘witty characterizations of inferred subjects’.6 But in this unconventional take on portraiture Antin also questioned what form representation of the subject could or should take. As such, this series and Portraits of Eight New York Women represent the development of the ideas that Antin had been exploring in Blood of a Poet Box.

The Portraits of Eight New York Women series seems particularly closely linked to Blood of a Poet Box, both in its subject matter (Antin’s social and creative circle) and its approach, which Antin herself has described as more sociological and less invested in stereotype than the slightly earlier California Lives.7 While the subjects of California Lives are generic types identified by first names only,8 the eponymous subjects of Portraits of Eight New York Women are gallerist Naomi Dash, painter, critic and gallerist Amy Goldin, anthropologist Margaret Mead, poet and playwright Rochelle Owens, dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer, painter and performance artist Carolee Schneemann, museum publicist Lynne Traiger and poet Hannah Weiner.9 Like Blood of a Poet Box, this series operates as a group portrait of sorts, although in this case the eight works also function independently of each other and, as art historian Lisa Bloom has noted, the group is notable for its emphasis on difference rather than universal experience.10 Portraits of Eight New York Women existed in two iterations: first as a set of anecdotes presented in short printed texts and shown at the exhibition 2,972,453, the first of critic and curator Lucy Lippard’s co-called ‘numbers shows’, which was held in Buenos Aires in 1970.11 The second iteration combined these texts with assembled collections of new consumer goods that Antin ordered from the Sears retail catalogue to produce a group of works that she first exhibited in room 322 of the Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street, New York, in 1971. The exhibition flyer listed the eight subjects of the work and posed a series of questions related to identity and identification:

If you were a food, what food would you be?

If you were a garment, what garment would you be?

If you were an appliance, what appliance would you be?

If you were a room, what room would you be?

If you were an illness, what illness would you be?

If you were a war, what war would you be?12

Fig.4

Arman (Armand Fernandez)

Condition of Woman I 1960

Glass, wood, fabric, plastic, cork and metal

1920 x 462 x 320 mm

Tate T03381

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

The press release that accompanied the Chelsea Hotel exhibition stated that ‘The artist considers herself a special variety of representational sculptor and each of her pieces as a rigorously realistic “portrait from which the sitters happen to have walked away”’.13 This assertion of the realistic nature of Antin’s sculptures both speaks of their seriousness as conceptual propositions and hints at the affinities that the series has with the work of other artists engaged in the project of redefining realism during the 1960s, such as the nouveau réalistes in France and the arte povera artists in Italy. In re-presenting the portrait in conceptual and consumer terms, these works are similar to those by artists such as Arman, whose Poubelles series, produced from 1959 onwards, represented his sitters by means of glass vitrines filled with refuse (see, for example, Condition of Woman I 1960, Tate T03381; fig.4). Like Arman’s project, Antin’s consumer portraits elevate apparently ‘low’, non-art materials to the status of artwork. They also seem to retain the elements of intimacy and indexicality that is central to Blood of a Poet Box. Like the latter, Antin’s Portraits of Eight New York Women suggest some physical or biological trace of their sitter – skin cells left behind on a pair of nylon stockings or on a shower cap, perhaps. According to art historian Ernst van Alphen, this kind of object portrait rejects the element of visual similarity on which conventional portraiture relies, instead presenting the subject by means of contiguity: objects that have been in contact with a person acting as a stand-in for them.14 However, in 1977 the art historian Jonathan Crary disputed the extent of this emblematic equivalence, describing the way in which, in Antin’s consumer portraits, ‘her objects and commodities circle ambivalently around a missing presence, a lost center, to which they have no direct link.’15

Antin’s assemblages of brand new consumer goods, purchased for the piece from the Sears catalogue, certainly refuse any personal biographical narrative or the sense of nostalgia that is brought about by the outmoded status of Blood of a Poet Box’s medical box and slides. Furthermore, the quotidian and often intimate nature of her selection of objects in these works – among them a pair of stockings, a thermos, a sweatshirt, a shower cap, a tray of cat litter – belies the traditions of portraiture as a genre that conveys the high social status of its sitter. The objects in this case are universally and cheaply available from a national mail order catalogue. But they hint at some personal significance known only to the subjects’ inner circle, of which Antin was a member. Indeed, of her eight subjects, half (Owens, Rainer, Schneemann and Weiner) had also been included in Blood of a Poet Box.

Public image, private self

Fig.5

Eleanor Antin

Library Science 1971

© Eleanor Antin

Antin’s consumer portraits reveal the way in which our sense of others and ourselves is shaped by public display, and in this respect they are related to the historical convention of representing the status of sitters via the inclusion of material possessions. Exploring the nature of portraiture in a conceptual and non-figurative mode, these works also highlight the role of consumer culture in shaping our perception of ourselves and the people around us. A further investigation into the nature of selfhood is to be found in Antin’s 1971 work Library Science (fig.5), first shown in an all-woman exhibition that she had helped to organise at the San Diego State College Library, and then at the Brand Art Center in Glendale, California. Here, as Antin describes it, ‘each participant in the exhibition of women artists was asked to provide me with a “piece of information” of any form that described or represented her self, her life, her work, or any aspect of herself that she felt appropriate at this time’, and this information was then classified according to the Library of Congress system and displayed alongside its catalogue card.16 Among the material that Antin received and included were a pair of clogs (assigned the classification GN/498: Arms and Armor, Primitive); a dental plate (NK/7412: Plate); and a quotation from psychiatrist R.D. Laing (whose status as ‘a beacon of light to a whole generation of young romantics’ led Antin to the unorthodox classification VK/1012: Lighthouse Tenders).17 In all cases Antin’s group portraits tread the line between public image and private self and stage identity as a shifting set of social signifiers in a manner that extends the project of Blood of a Poet Box, which had approached with some irony the idea of inherent biological identity.

Fig.6

Eleanor Antin

Representational Painting 1971 (film still)

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

© Eleanor Antin

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

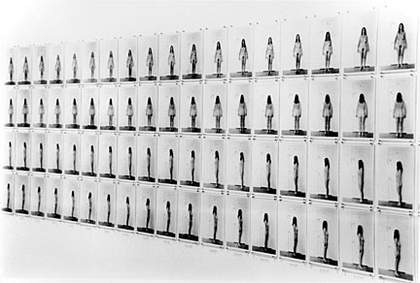

Fig.7

Eleanor Antin

Carving: A Traditional Sculpture 1972, detail

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

© Eleanor Antin

In two later works, Antin would continue to explore the idea of artistic and art historical conventions: the black and white silent video work Representational Painting 1971 (fig.6) and the multi-part photographic work Carving: A Traditional Sculpture 1972 (fig.7) played with the methods and expectations associated with art’s established media. In the former, Antin is seated in front of the camera painstakingly applying makeup for 38 minutes; in the latter, 148 photographs of the naked artist chart her gradual loss, through dieting, of ten pounds over thirty-seven days. Both works represent a contemporary updating of traditional artistic media, where paint is replaced by makeup, and the sculptor’s chisel by the dietician’s rules. They also engage with the conventions of self-portraiture, albeit approached from a postmodern perspective.

Representational Painting and Carving: A Traditional Sculpture enact the ritual of constructing a public image: ‘the human life’, Antin observed, ‘is constructed much like a literary one, and, in any event, the documentation is the same for both’.18 Cultural signifiers act not only to mediate between self and world; they actively form the subject. Furthermore, in Representational Painting as in Blood of a Poet Box, Antin seems to be suggesting that the act of representation can actually serve to obscure meaning and identity, rather than making it clearer to see.

The fascination with picturing, the relationship between image making and self-image, transformation and self-(re)presentation, was manifested in Blood of a Poet Box as in these later works as an interest in traditional art and ‘ironically playing with the idea of it’, according to Antin.19 In this respect, such works continue the project of early poems that Antin had written, such as ‘The Way to Copy a Mountain from Nature (for Diane Wakoski)’ and ‘How to Paint Wounds’, both written in the mid-1960s and both of which reveal an interest in the mechanics of depicting the world.20 Although Blood of a Poet Box marked Antin’s departure from the written word and her move into art, it seems that her interest in the techniques and politics of representation predated this development.

If Antin’s works from the 1960s and 1970s interrogate and complicate identity and its signifiers, then they do so in a way that demonstrates the artist’s awareness of cultural histories and structures. The green box in which Antin’s slides are housed is one produced specifically to hold medical specimens, but it is also reminiscent of a museum display case, library card catalogue or art historical slide collection. The work links the labour of gathering blood samples to the construction of the early modern Wunderkammer (cabinet of curiosities) or scholarly collection of knowledge embodied in the library, archive or museum collection;21 the rationale of these early forms of display helps us to understand the meaning of Antin’s work. Just as the Wunderkammer or library represented and classified the universe in microcosm, so Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box represents in tiny samples the larger artistic and poetic world of which she was a part. Furthermore, if the items in a Wunderkammer denote rarity and exclusivity, so the poets in Antin’s box might be valued for these same qualities. The box might thus be seen as creating a form of canon, listing those poets deemed most valuable to Antin during the period she made the box, those worth remembering for posterity. Indeed, the slide collection was, until recently, the means by which art historical learning was acquired and transmitted (although here Antin substitutes blood drops for masterpieces). The viewer is left to wonder how Antin made her selection, what might unite these subjects apart from their profession, and what their ordering could denote. Thus Antin’s project references not only conventional forms of representation such as the portrait, but also engages with the history and theories of collecting and display of cultural and natural objects. It implicitly draws out the link between a collection and the assertion of value or prestige, while suggesting the subjective nature of such determinations. The interest in traditional art that Antin expressed via these early works extended to an interest in art history and the systems of value that it constructs.

Throughout her career Antin has been attuned to the politics and rhetoric of traditional art in all its guises, engaging with art history in order to highlight the ways in which representation can tell only partial truths. In Blood of a Poet Box, Antin uses portraiture, with all the conventions and prejudices that historically have attended that genre, as a means to challenge assumptions about the locus of human subjectivity. Blood of a Poet Box, like Antin’s later projects, is as much a work about the process of representing as it is a representation. Its subject is portraiture and its visual conventions and social assumptions as much as, if not more than, the one hundred poets that are named inside its lid. As such, Blood of a Poet Box might be seen to sit within the realm of postmodernism as it developed from the 1960s into the following decade. Antin’s box not only indicates the futility of portraiture’s claim to ‘capture the essence’ of its sitter – by means of literalising that metaphorical turn of phrase – but it also suggests that subjectivity is contingent upon social relationships and therefore subject to change. Blood of a Poet Box is, therefore, both a portrait and an anti-portrait: it can be read as a critique of portraiture, but it also relies on the conventions and assumptions of portraiture to critique ideas about the authentic subject.