The art of Anselm Kiefer has evolved over the last thirty years through a process of layering, interweaving and reworking of themes, motifs and patterns that encircle and intersect with one another across very different media: photographs, gouaches and watercolours, paintings, books, prints, sculptures, installations and studio mises en scène, which are then photographed and provide material for further books, gouaches and paintings in their turn. The more time we spend with his work, and the more adept we become at finding our bearings within it, the greater is our sense of it as a kind of labyrinth.

Daniel Arasse, Anselm Kiefer (2001)1

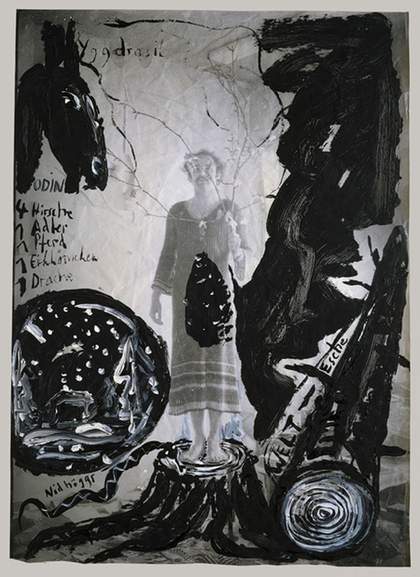

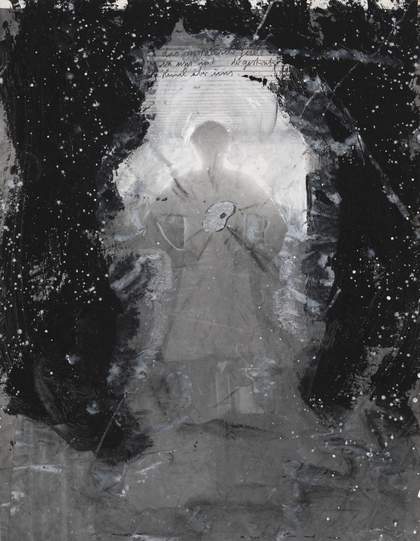

Fig.1

Anselm Kiefer

Yggdrasil c.1980

Gouache and acrylic on photograph

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Anselm Kiefer

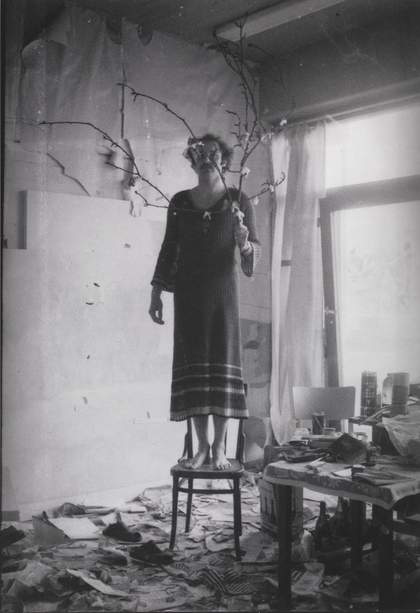

Fig.2

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Photograph, black and white, on paper

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

A good example of the interweaving in Kiefer’s art to which the art historian Daniel Arasse refers is the work Yggdrasil 1980 (fig.1). This draws on, and literally paints on, one of the transvestite photographs that Kiefer had taken a decade or so earlier as part of his 1969 Occupations performance and Heroic Symbols photographic project, and included in his subsequent artist book For Jean Genet (Für Jean Genet) 1969 (Tate AR01163; fig.2). Yggdrasil is the World Tree in Norse mythology, a giant ash that links and shelters all worlds and under whose branches the ‘fates’ known as the Norns spin threads of destiny. The motif of the tree and its connection to Norse mythology recurs frequently in Kiefer’s work. For instance, in Urd, Verdandi, Skuld (The Norns) 1983 (Tate AR00036), its presence is implied by the twine that descends from gaps in the ceiling over a burning pyre that is in danger of igniting the hall of heroes – an imaginary conflation of Valhalla and architect Wilhelm Kreis’s Funeral Hall of the Great German Soldiers in Berlin, which was a forbidding symbol of National Socialist architecture. In Yggdrasil, by contrast, Kiefer becomes the trunk of this ash tree, bearing branches in an interesting form of body art.

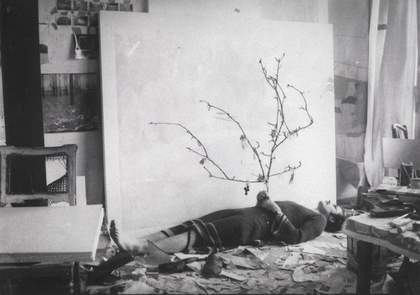

Fig.3

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

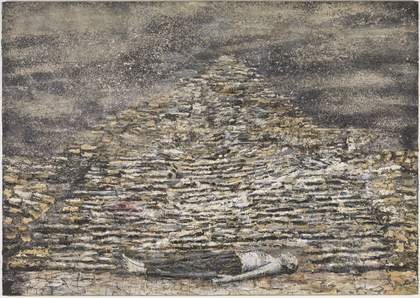

Fig.4

Anselm Kiefer

Man under a Pyramid 1996

Emulsion, acrylic paint, shellac and ash on two canvases

3545 x 5035 x 95 mm

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

In a related photograph from Heroic Symbols Kiefer lies on the floor of his messy studio in a crocheted dress with a branch seemingly emerging from his abdomen (Tate AR01173; fig.3). This iconography of a tree or plant sprouting from a human form has a long tradition in art and mythology and can be traced back to the fourteenth-century Ashburn Manuscript.2 The 1969 Heroic Symbols photographs are the source of many other works by Kiefer with an arboreal or celestial theme, such as Man Lying with Branch 1971 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Man in the Forest 1971 (Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco) and Gilgamesch and Enkidu in the Cedar Forest 1981 (Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao), through to later works of the 1990s such as Falling Stars 1995 (private collection) and Man under a Pyramid 1996 (Tate AR00037; fig.4), the latter showing the artist lying in a supine position under the vast expanse of the heavens, forging a relationship between himself and the stars.

Fig.5

Anselm Kiefer

The starry heavens above us, and the moral law within (Über uns der gestirnte Himmel, in uns das moralische Gesetz) 1969–2010

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

Fig.6

Anselm Kiefer

The moral law within us, the starry heavens above us (Das moralische Gesetz in uns, der gestirnte Himmel über uns) 1969–2010

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

In addition, a series of artworks created by Kiefer in 2010 that adapt famous lines from the work of German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1824) are further examples of the recurrence of certain motifs and imagery throughout Kiefer’s practice. These artworks were made around the time that Kiefer was producing his new Occupations installation for the Gagosian Gallery in New York based on the 1969 Heroic Symbols photographs. Again he references earlier works, this time those from 1980–1 which already reuse the 1969 photographs, as well as celestial works from the period 1995–2000. There are two key artworks from this series in the Tate ARTIST ROOMS collection: the painted photographs The starry heavens above us, and the moral law within (Über uns der gestirnte Himmel, in uns das moralische Gesetz) 1969–2010 (Tate AR01164) and The moral law within us, the starry heavens above us (Das moralische Gesetz in uns, der gestirnte Himmel über uns) 1969–2010 (Tate AR01165) (figs.5 and 6). The former uses and manipulates a 1969 Heroic Symbols photograph of Kiefer giving the Sieg Heil salute from within the Temple of Athena in the Forum Romanum in Paestum. The photograph is overexposed, making the saluting figure seem apparitional, a ghost-like presence that floats through time and space, still appearing across Kiefer’s work many years after he first ‘embodied’ that role as performer of the Sieg Heil gesture. In The moral law within us, the starry heavens above us, Kiefer also refers back to the 1969 Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet photographs, but this time one of the Karlsruhe studio photographs of the artist in a white shift with his hands on hips. Kiefer seems to use photographs almost like Wagnerian leitmotifs in a process of recurrence and recontextualisation, which often leads to new interpretations.

In these artworks Kiefer has painted an artist’s palette over his heart with individual lines radiating from it, citing his many other artworks from the 1970s that feature such palettes, but more specifically the photo-painting Starry Heaven (in German Der gestirnte Himmel) of 1980. The starry heavens above us was also Kiefer’s first artwork to adapt the closing lines from Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason (1788): ‘Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me’.3 In The starry heavens above us the ruined temple of Athena is roofless and Kiefer salutes the painted starry black firmament. It is an artwork that can also be related to paintings of the second half of the 1990s, such as The Renowned Orders of the Night 1997 (Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao), which shows Kiefer contemplating the immense mantle of stars, and which is also a testament to his interest in the Renaissance theorist Robert Fludd, who insisted on correspondences between micro- and macrocosms. As the art historian Matthew Biro has pointed out, ‘Kiefer’s constellations were conscious inversions, “negatives”, of the daytime sunflower paintings from Barjac, canvases that depict black seeds dispersing through the air’.4

After Kiefer’s dramatic use of his own body in Occupations and Heroic Symbols, his ‘attic’ paintings of 1973 are notable for their sinister desolation, the only trace of human presence being in the inscriptions across the wood grain interiors. These inscriptions are particularly evident in the monumental painting Germany’s Spiritual Heroes 1973 (Collection of Barbara and Eugene Schwartz, New York), which is connected to the Heroic Symbols books of 1969 in its use of a similar roll call of names taken mainly from German cultural history. These include Richard Wagner, Caspar David Friedrich and Joseph Beuys, and while in the book project they appeared as inscriptions on a page, in Germany’s Spiritual Heroes they resurface along the wooden floorboards depicted in the painting. The work reveals how Romantic literature and art was ‘misused’ by National Socialism, that is to say utilised by a rotten regime to legitimise itself.

Fig.7

Anselm Kiefer

Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom (Lasst Tausend Blumen Blühen) 2000

Oil paint, shellac resin, wood, metal string and screws on canvas

3803 x 2805 x 54 mm

Tate

© Anselm Kiefer

The Heroic Symbols photographs are also connected to another series of works that Kiefer created in the year 2000, the mixed media paintings collectively titled Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom that feature the Chinese communist leader Chairman Mao Zedong (1893–1976) (fig.7). In 1993 Kiefer had travelled across China and the paintings he made seven years later were based on photographs he had taken there, especially of monumental statues of Mao, thereby continuing a practice of recycling photographs for artworks often created some time after they were originally taken, a practice that started with Heroic Symbols. It could be argued that his paintings of 2000 were a belated response to the ‘little red book’ Maoism that preoccupied many leftist artists and writers in the late 1960s and early 1970s, such as Jörg Immendorff, who made a number of ‘Maoist paintings’. As Kiefer has stated:

In the 1960s, in Europe and Germany, Mao was a moral institution. Students were looking to the Little Red Book [which contained quotations from Mao] for solutions … but I was already a bit critical of this. I thought there was a lot of propaganda around Mao … I was fascinated, and I admired Mao, but at the same time, I also thought something was wrong.5

![Andy Warhol [no title] from the series Mao Tse-Tung 1972](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig8warholfromtheseriesmaotsetungtatep77081.width-420.jpg)

Fig.8

Andy Warhol

[no title] from the series Mao Tse-Tung 1972

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Right Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

In 1967 more than 100,000 copies of Mao’s Little Red Book were bought by West Germans, and at its peak German Maoism had over 10,000 members.6 Unlike Immendorff, Kiefer was more interested in deconstructing the iconic image of Mao, a deconstruction not dissimilar to his treatment of Hitler, and over the course of his career it seems clear that the artist has been preoccupied with investigating the processes of iconicity and iconoclasm. In this regard, there are points of contact between Kiefer and Andy Warhol, the latter making iconic and ironic screenprints of Mao in 1972 (see Tate P77081; fig.8). However, the dystopian melancholic tones and strange textured materiality of Kiefer’s mixed media paintings, works that almost appear physically and metaphorically archaeological in working through layers of history, seem visually far removed from the glossy colour surfaces of Warhol’s parodic pop art.

In a 1957 speech Mao said ‘let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend’, and for the title of his ‘bi-millennial’ paintings Kiefer raised the number of flowers to a thousand. This may be an echo of the Maoist slogan ‘To go on a thousand “li” march to temper a red heart’ that featured on a 1971 poster depicting young people marching to Beijing to pledge their allegiance to the communist leader. The intellectual freedom promised by Mao was short-lived, however, and as was the case in Stalin’s USSR and Hitler’s Germany, intellectuals who criticised the regime were quickly arrested and often executed. In Tate’s work from the series, Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom 2000 (Tate T07841), Kiefer depicts Mao as a ghost-like presence partially obscured by dried roses and tangled brambles. The art critic Thomas McEvilley has written of Kiefer’s Mao series: ‘It is as if he [Mao] were trapped in his own despotic image, saluting it amid the flowers without knowing that he was saluting his own failure’, presenting a clear visual connection to the Heroic Symbols photographs.7

Although it is not known whether Kiefer knew Liu Chunhua’s painting-turned-poster Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan 1968 when producing his Mao series, it seems likely given the image’s subsequent fame. In this work, which in composition and mood recalls Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog 1818 in the Kunsthalle Hamburg (a painting to which Kiefer responded in Heroic Symbols), a young Mao stands heroically before a group of mountains, his clenched left fist representing his revolutionary will. By contrast, Kiefer represents Mao as a middle-aged figure wearing a long, heavy overcoat, a garment reminiscent of the military overcoat that the artist donned for Heroic Symbols, and his right arm is raised in a salute that echoes the Sieg Heil gesture in Heroic Symbols. It has been argued that Maoist communism had its roots in the German Idealism of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Ludwig Feuerbach, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,8 and that German National Socialism took its cues from German Romantic Idealism combined with primitive Darwinism.9 Among these strands of influence there are points in which the extreme right and the extreme left meet, and Kiefer seems to be interested in exploring the dangers inherent in all forms of idealism, or rather the potential for the ideas of philosophers and writers to be misused by despots. In doing so, Kiefer has often been exposed to the possibility of misinterpretation, as Biro has observed: ‘Many of Kiefer’s works simultaneously support both left-wing and fascist readings’.10

Kiefer’s meditations on Mao may also be analogous to his reflection on the division of Germany during the Cold War, and it is worth bearing in mind the painter Georg Baselitz’s provocative comment that ‘the only difference between East Germany and Nazi Germany was the uniforms.’11 Of the relationship of Mao to Kiefer’s earlier work, the collector and curator Anthony d’Offay has written: ‘The flashback to Kiefer’s early series Occupations is inevitable … Mao Zedong and Adolf Hitler were born within four years of each other and were part of the same huge revolutionary cycle which shaped the past century and could so easily be repeated in the years to come’.12

New Occupations

Kiefer’s reutilising and recontextualising of his Heroic Symbols photographs since they were made in the late 1960s arguably results in a very different viewing experience as they reappear across different media. Art historian Lisa Saltzman has commented that the eight Heroic Symbols oil paintings that Kiefer made in 1970 create a markedly different effect to the book images by introducing the factor of scale, with their ‘sheer monumentality lending a weight and presence to the image that the early books simply could not convey’.13 This comment has even greater resonance if we consider the new version of the photographic project (entitled Occupations) that Kiefer created in 2010 for an exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in New York, which included some of the original images enlarged to mural size. These were printed onto seventy-six colossal lead sheets that were suspended from long steel hooks below fluorescent lights in a huge steel container (fig.9).

Fig.9

Anselm Kiefer

Installation view of the 2010 solo exhibition Next Year in Jerusalem at Gagosian Gallery, New York, showing Occupations (Besetzungen) 2010 (right)

© Anselm Kiefer

As well as reusing many of the images printed in 1969 as part of the Heroic Symbols group, the installation also included newly rediscovered photographs from the original project. In the process of moving artworks from his Barjac studio to Paris in 2007 and then to Croissy-Beaubourg in 2009, where he set up new studio spaces in the huge former depot of the Parisian department store La Samaritaine, Kiefer rediscovered several hundred negatives from his 1969 performance that had never been developed, simply because at the time he did not have the financial resources to make so many photographic enlargements.14 Since 2009 this find has led to new works in various media, including the transfer of photographs from Heroic Symbols onto the Jericho towers that were central to the set he designed for his opera and installation In the Beginning (in German Am Anfang) at the Opéra Bastille, Paris, in 2009.

For the Gagosian exhibition Kiefer made the large-scale photographs on lead sheets that could be glimpsed through half-open front and side doors but were so closely packed together that they were mostly concealed. The installation was like a huge analogue memory storage facility holding the secret files of some impermissible history, but on a container scale that also gave rise to bleak associations of detention and internment. These associations were heightened by the fact that Kiefer’s latest paintings of the archetypal German forest could also be sighted through the leaden shrouds – mixed media paintings that included such unorthodox yet darkly suggestive materials as thorn bushes, synthetic teeth and snakeskin. The installation could also be seen as an unearthed time capsule, the mature artist having excavated a rusting brutalist structure containing a forbidden archive of faded images from the earliest phase of his career, all presented under the cold glare of fluorescent strip lights that hark back to those of his Karlsruhe studio of the late 1960s. The heavy half-open doors at the front end of this steel capsule seemed to both invite and deny entry, especially as they framed head-on a darkened image of Kiefer embodying the role of the saluting German occupier.

The fact that the doors are only half shut may have been part of the artist’s resistance to the closure, in relation to biographical histories of the Holocaust, of what the Spanish writer and politician Jorge Semprún called the ‘cycle of active memory’.15 As the writer Marina Warner has observed, in creating the ‘new’ version of Occupations Kiefer was intent on refusing to allow ‘the memory of Fascism to be quiet’,16 and there is a sense that the absurdity or parody in the earlier project has been supplanted by something more desolate, brooding and commemorative, but perhaps something that also warns of cyclical historical patterns and the dangerous resurgence of dark political forces in the world. For instance, Kiefer’s use of lead in the 2010 installation – one of the artist’s signature materials – has numerous connotations, but in her poetic essay on the artist Warner cites an important article by the writer Peter Koch in which he states: ‘Lead was thought to be durable and crude: a sick metal. The message becomes infected by the medium. Demons are in lead, gods are in gold’.17