The Doll’s House (Tate N03189; fig.1) is one of three paintings (see also figs.3 and 4) that the British artist William Rothenstein started in the summer of 1899 while holidaying in Vattetot-sur-Mer, a commune on the Normandy Coast in France, and finished in early 1900 at his studio in Kensington, London. Vattetot and nearby Étretat, located about forty miles west of Dieppe, were well known for their limestone cliffs, which had been painted by Gustave Courbet, Claude Monet, Eugène Boudin and Eugène Delacroix.1 These cliffs featured in several of Rothenstein’s later works, such as White Cliffs, Vaucottes 1908 (Tate N05436), as did the local farmhouses, seen in Norman Hamlet c.1910 (Tate N05997).2 During this initial visit, however, Rothenstein focused his attention inland, or, in the case of The Doll’s House, inside one of the old cottages where the artist was staying with his new wife Alice (née Knewstub), an actress he had first met four years before.

Fig.1 William Rothenstein

The Doll’s House 1899–1900

Oil paint on canvas

889 x 610 mm

Tate

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

The 1899 holiday was something of an extended honeymoon: William and Alice had married on 11 June and taken off to Vattetot, via Dieppe, for a two-week break.3 Their enthusiasm for the region encouraged them to rent the cottage for the whole summer, returning in late July with friends and family in tow. One of these – the Welsh artist Augustus John – would join Alice in modelling for The Doll’s House. Other members of the party included Rothenstein’s younger brother Albert (later Albert Rutherston), the artists Charles Conder and William Orpen, Alice’s sisters Grace and Christina Knewstub, the solicitor-cum-gallery-manager Arthur Clifton and his wife, and the art enthusiast and Manchester councillor Charles Rowley.4 Orpen, John and Albert Rutherston were all students at the Slade School of Art in London – which William had attended ten years before – and moved very much as a trio during this time, so much so that they dubbed themselves ‘The Three Musketeers’, no doubt inspired by The Musketeers, the play in which Alice Rothenstein had recently appeared under the stage name of Alice Kingsley.5

Although all the written accounts suggest a summer idyll consisting of (in Rothenstein’s words) ‘wonderful days and wonderful nights’, it wasn’t necessarily a restful trip, at least not for Rothenstein, whose workload was especially full at this point in his career.6 Clifton’s presence reminds us that Rothenstein had recently been a key figure in the foundation of Carfax and Co, a small commercial gallery in St James’s, Piccadilly in London, which was about to launch an ambitious programme of exhibitions.7 Charles Rowley was also there on business, hoping to persuade Rothenstein to do a series of lithographic portraits of prominent Manchester figures, a companion piece to his recently published Oxford Characters (1896).8 Rothenstein was also in the final stages of a book – the first English monograph on the Spanish artist Francisco Goya (1746–1828), published in 1900 – that he had been writing for some time and that had its origins in a visit to Spain in 1894–5. Although the group evidently had a lot of fun at Vattetot (‘never such patisserie, we thought, as we found there’, recollected Rothenstein) the pressure of work was never far away.9 With artistic reputations to build, none of the artists could afford to be idle. Albert was especially keen to remind his parents that this was not all about smoking, drinking, bathing and bicycling, as the following breakdown of a typical day suggests: ‘up at 7-30 – Chocolate – Work – bathe at 11 – dejeuner at 12 – work till dinner, after dinner we walk + sit in the café and smoke’.10 As Rothenstein recalled in his memoirs: ‘never had so many easels and paint-boxes been seen [at Vattetot]. It was a glorious time, divided between painting and play’.11 ‘Industry was the order of the day,’ confirmed Augustus John, ‘industry and, in the evenings, calvados.’12

All of the artists produced a significant body of work. Orpen, for instance, as well as making various amusing sketches of the group, was planning his entry for the Slade School painting prize, The Play Scene from ‘Hamlet’ 1899 (now at Houghton Hall in Norfolk), which, like The Doll’s House, featured portraits of his friends, including Albert and Augustus.13 When not modelling for his friends’ compositions, John was drawing landscapes – and Grace Knewstub.14 Albert Rutherston was working on studies for a painting called Bathers (now lost) and his own version of Hamlet.15 Reports suggest that he was the least industrious of the group, preferring to read rather than draw, a habit that reflects the general tendency of the whole group to seek inspiration from literature, from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play Faust (1808) to the novels of William Makepeace Thackeray.16 Charles Conder, the elder statesman of the party, was working on his painted silk fans, such as Fan: The Romantic Excursion 1899 (Tate N03194), which seems to have been painted at nearby La Roche-Guyon, and on his lithographic series The Balzac Set, which would be published and sold at the Carfax later that year.

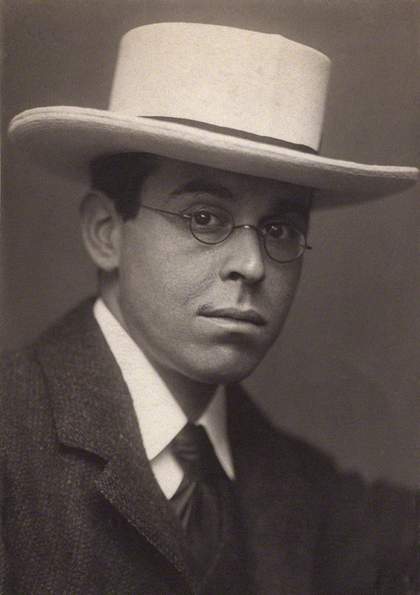

Fig.2

George Charles Beresford

William Rothenstein c.1902

© National Portrait Gallery, London

It was the paintings that William Rothenstein produced this summer, however, that would go on to have the greatest impact, The Doll’s House in particular. In many ways, the summer in Vattetot could be seen to represent a crossroads in Rothenstein’s career. Old friendships – such as that with Charles Conder, whom Rothenstein had met in Paris in 1890 – were giving way to the new, most obviously that with John, whom Rothenstein regarded as one of the great hopes of British art. Rothenstein may have sensed, as the century drew to a close, that he could no longer live off his reputation as a clever young artist who had studied in Paris. Reviews of New English Art Club exhibitions from the 1890s consistently outlined Rothenstein’s youthful potential; by 1899, however, he was rapidly becoming a more senior figure and risked being seen as a relic of the 1890s if he did not show signs of moving into new territories.17 By associating himself with John and Orpen – ostensibly the friends of his younger brother – he hoped to enter the new century looking forward and not back, to establish himself as one of the leading painters of his generation, rather than merely a promising draughtsman and printmaker. The somewhat glum face that stares from beneath the Edwardian boater in his 1902 photographic portrait (fig.2) is indicative of Rothenstein’s change in attitude, suggesting that the witty ‘Will Rothenstein’ of the 1890s has given way to the serious-minded ‘William Rothenstein’ of the 1900s. The Doll’s House, which attracted significant critical attention, marks another step in this direction. In the words of his friend, the critic D.S. MacColl, the painting ‘marked a new stage in his career’.18 ‘Before he painted The Doll’s House,’ recalled the critic Frank Rutter in 1933, ‘Will Rothenstein was known as an accomplished draughtsman with a high gift for portraiture; immediately afterwards he was recognised and accepted as one of the English painters who counted.’19 At the same time, the painting also stands apart from much of his oeuvre, tackling a subject and evoking a mood which finds few obvious parallels in his later work.20

A man, a woman and a staircase: these are the seemingly simple foundations on which The Doll’s House is built. This simplicity carries over to the tone of the painting: a symphony of ochre, brown and black, lightened only slightly by the white of the woman’s dress and the pink of her face. There are grounds for calling the painting a double portrait, yet there is something about the position and pose of the figures that makes this reading difficult. The intimacy of a portrait – the sense of a connection being made between viewer and subject – is missing, with both figures being represented at a remove. They are positioned, informally, on the far side of a starkly decorated and low-ceilinged room, against a rough damp wall, in poor light, the female figure with her eyes closed or looking downwards and the male with his arms folded. However, it is not only this body language that forms a barrier between subject and viewer: there are literal barriers also. The woman is caught between a menacing shadow, an equally menacing shadowy figure, the wall and the dark wooden balusters of a narrow staircase. The man looks back at us, but his gaze seems distant and distracted.

The staircase is, in a sense, the real hero of the painting; indeed, it may even have been the starting point. The artist claimed to have been struck by the oddness of the ‘little staircase leading upstairs from the single sitting-room’ of the converted farmhouse in which he was staying at the time, and seems not to have been able to resist using it in one of his compositions.21 Certainly it must be central to any reading of the painting, offering as it does fascinating compositional and narrative possibilities. The pleasing interplay of verticals and diagonals, taken up and further explored by the man’s bodily position, creates a kind of compositional vortex, at the centre of which we find the patch of blank wall that separates the two figures whose simultaneous physical proximity and emotional distance from each other forms the crux of the painting’s tension. Like the London fogs of which James McNeill Whistler was so fond, this staircase operates as an atmospheric device: a shadow machine, manufacturing claustrophobia – or worse. In a 2003 article on the painting, photographer Chris Shaw (whose own work explores mysterious figures in interiors) referred to this shadow emanating from the staircase as ‘an amorphous blackness in which you could imagine yourself losing everything – your position in society, your security, your entitlement … your soul’.22 The shadow cast by the standing man is described by Shaw, meanwhile, as ‘a huge black hole of metaphysical vomit’.23 Shaw’s visceral reaction to two patches of brown-black paint stands as testament to Rothenstein’s ability to squeeze maximum tension out of very basic elements.

The staircase fills the frame: we know nothing else of the so-called sitting-room from which it ascends (the room that we are effectively in), and nothing about where it leads, except that access to the latter would involve being engulfed in the heavy shadow behind the woman. What we do know is that our path, should we want to go up the staircase, is blocked. The staircase is not being used as a staircase should – as a means of moving from one space to another – but as a space of waiting. The woman is seated halfway up the first flight of stairs, with her leg inelegantly crossed and her head resting on her hand.24 She does not appear to have moved for a while or have any intention of moving soon. She wears a dark shawl over a white dress, whereas the standing man, in his ‘tight jacket and wide pegtop trousers’, already wears a hat and carries a dark mackintosh over his arms.25 The seeming implication, as John would later suggest, is that the figures are about to go somewhere, but have decided against it.26 However we choose to read it, it is clearly a representation of an impasse. Crossed legs and crossed arms suggest a clear communication failure between the man and the woman, one of them firmly lodged on the stairway, the other rather menacingly poised on its edge with one foot pressed firmly against the centre of the first step. Is she blocking his way up or is he blocking her way out? The artist seems to have taken care that their facial expressions are hard to determine. The woman could be read as meditative or frustrated, brooding or simply taking a nap, while the man could be ruminating or merely bored. The level of detail with which their faces have been painted breaks down when we try to read their expressions. What we thought was a living, breathing figure becomes oil paint again. The only thing we can say for sure is that neither figure seems to be concentrating on anything outside of themselves; their gaze is instead an inward one. They are with us, but not with us.

Despite the literary title and the fact that John posed for the painting, many commentators have argued that the interest of The Doll’s House lies primarily in its formal attributes, and that the ‘official story’, as Chris Shaw calls it, may even act as an impediment to appreciating the picture (‘who cares about all that when we have our own imagination?’, Shaw asks).27 This idea had been proffered by several contemporary critics. Writing for the New York Tribune in 1900, the critic R.C. suggested that:

the subject [of The Doll’s House] was probably the last thing that concerned Mr. Rothenstein. What interested him was the play of light and shade, the contrast between the brightly illuminated wall on the right and the obscurity of the staircase to the left, on the lower steps of which a sad faced woman is seated, indifferent to the picturesque man who stands, back to the wall, in front of her.28

Reflecting back in the 1930s, Frank Rutter drew similar conclusions, noting that while ‘the subject helped … Ibsen was in the air, so to speak, and his plays were being heatedly discussed in all circles’, the painting may not have been noticed in the first place were it not for its ‘masterly’ treatment:

The simplicity of the composition, the gaunt chevron of the staircase, the tremulous lighting of the bare wall, the dark, silhouetted figure of the standing man, the subtly illuminated figure of the girl, the intensity of the vision, the reticence of the colouring, the suave surface of the brushwork – all these combined to make an overwhelming impression on the spectator.29

As these responses suggest, The Doll’s House owes its impact primarily to the brilliant simplicity of its composition – to what Hubert Wellington, author of the first monograph on Rothenstein, described as the painting’s ‘very happy design’.30 Chris Shaw’s belief that the painting is a ‘timeless scene’ with the power to affect viewers who have no knowledge of the personal, social and artistic contexts in which it was produced is not to be scoffed at.31 It leads us back, after all, to the material object, and demands that we question what it is exactly, on the canvas, that sparks our imagination in the first place. Only once we are confident that we have really seen the painting can the wider context begin to be considered.

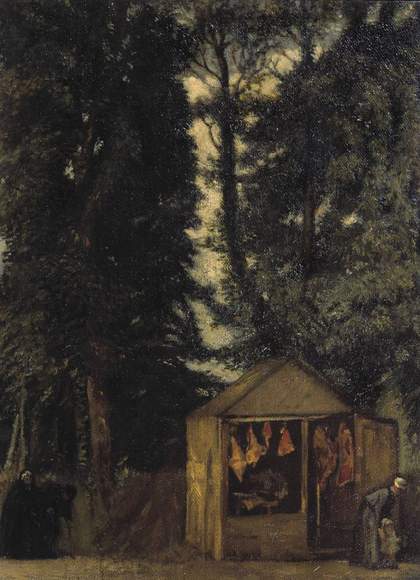

Fig.3

William Rothenstein

The Butcher’s Shop under the Trees 1899

Tate

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Although the three paintings that Rothenstein started at Vattetot (figs.1, 3 and 4) were probably never intended as a series, they share many similarities. To start, the dimensions of each are almost exactly the same, allowing for differences in the framing and variations in the stretching. When seen alongside each other, there is also a noticeable correspondence in the tone and composition. Acknowledging the yellowing of varnish, all three paintings are dark and employ a limited range of colours: mostly brown in The Doll’s House and brown, green and grey in Le Grand-I-Vert 1899 and The Butcher’s Shop under the Trees 1899 (Tate N05946). In each of the paintings Rothenstein has created spaces in which nothing much is going on, for instance the sky on the right in Le Grand-I-Vert, the blank wall in The Doll’s House and the thick wall of trees in The Butcher’s Shop. These areas are painted, as is the majority of each canvas, with broad and loose brush strokes, most obviously in the case of Le Grand-I-Vert, where paint seems to have been splattered on in parts. All in all there is little indication of the careful level of detail that Rothenstein would soon be employing in paintings such as The Browning Readers 1900 (Bradford Museums and Galleries, Bradford). The surface of all three paintings is instead uneven and heavily textured. In the case of Le Grand-I-Vert and The Butcher’s Shop this owes much to the coarseness of the canvas, which has a very thick and rough thread, as if the artist were painting on an old sack. The Doll’s House does not seem to have been painted on the same type of canvas, although it does share with Le Grand-I-Vert (but not The Butcher’s Shop) the use of a red ground, a habit Rothenstein claimed to have picked up from Goya and which he used in other paintings from this period, such as his 1894 portrait of the painter Jan Toorop (Tate N03850).32 As with Goya, the use of the earthy red ground, though barely visible in its unadulterated form, subtly transforms the layers of colour laid upon it, giving the paintings a rich and smoky depth.33

Fig.4

William Rothenstein

Le Grand-I-Vert 1899

Manchester City Galleries, Manchester

The most obvious similarity between the three Vattetot works lies in their distinctly moody quality. Le Grand-I-Vert takes place at night and features two or three figures lurking in the shadows of an anthropomorphic elm tree. A farm building extends across the right of the canvas and in the bottom right corner there is the faintest hint of a fiery glow indicating action occurring beyond the frame. The title of the painting is borrowed from Honoré de Balzac, although no literary reference is required to remind us that this is not a scene of moonlit tranquillity, but an essay in edginess.34

The Butcher’s Shop is a daylight scene, but the sky is blocked out by a group of tall, dark trees that dominate the picture. Other than the eponymous butcher’s shop (or shack), manned by a shadowy butcher, incident is provided by four figures, squeezed into the bottom left and right hand corners of the composition. These suggest that the painting is an allegory or memento mori charting the progression from the first steps of a child to the last steps of an old man. This rather melancholy story – fleshed out by the presence of the hanging hams, which serve as a reminder of bodily disintegration – is told, interestingly, in reverse. Whichever way you look at it, it is not an especially hopeful tale.

The essays that follow intend to show how a painting that bemuses people now was no less enigmatic to contemporary viewers. It is unlikely that the central questions of The Doll’s House – was it conceived as a double portrait, a literary illustration or a formal exercise? – will ever receive definite answers, which is why, in a sense, the painting has endured. Rothenstein took an old staircase in a converted French farmhouse, posed a couple of close friends on it, and through his careful management of small details, light and shade, not to mention the perplexing borrowing of a literary title, managed to conjure up a world of possibilities.