Tina Keane’s Faded Wallpaper was developed between 1986 and 1988 and took different forms during this period. This iteration, shown on three consecutive days in the newly opened Clore Studio at Tate in 1987, combined live performance with film footage and a recorded audio track to create a semi-immersive, multi-media work. Originally an installation, shown at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 1986, Keane performed the work at Tate Gallery in a combined programme with Richard Layzell, referred to in the Friends of Tate’s press release as ‘Performance Art’.1 After this event in 1987, a video-only version of the piece was produced, and has become the long-term version of the work. Based loosely on the 1890 novella The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Keane’s work also drew from texts by other prominent, creative women – such as Marion Milner’s On Not Being Able to Paint 1950 – as a means of exploring the nature of female identity, creativity, madness, and representation.

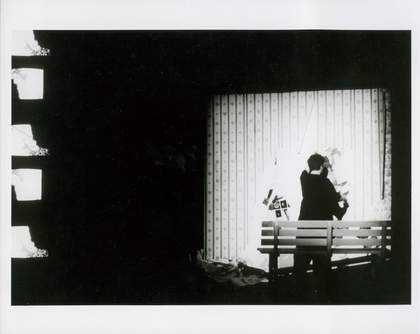

Keane’s work lasted forty minutes and involved her performing in synch with a number of video projections. The performance space was defined by a large central video projection, flanked by four projected pillars. Around the rest of the stage-area were four smaller video monitors and a bench, which was positioned facing towards the central projection. Initially sitting on the bench, looking at the projected video – which included images of women’s faces and hands, and the central symbol of the yellow, patterned wallpaper – Keane remained transfixed by the images as they began to change in front of her, emerging and then subsiding as if decaying. Periodically the images, which were distorted and unfocused, were ‘torn’ away by hands, revealing a layering of images of women – some body building, some synchronised swimming – fading in and out of the central wallpaper image. Many of these images had an abstract, or surreal quality about them, with faces being inverted and blurred, or projected upside down, and intersecting, cut clips feeding rapidly into one another. Keane experimented with video technology to find ways to create the effect of the images layering and merging into one another. The appearance of each new image, intercut with footage of women’s hands peeling and tearing, was to remove the wall paper, to work constantly at removing that which obscured the completeness of the images.

An audio track accompanied this process. Featuring excerpts from Perkin-Gilman’s story and aspects of Milner’s psychoanalytic text, the soundtrack also featured music at rhythmic odds with the images presented, adding to the sensory overload of the audience already confronted with a deluge of images. By contrast Keane’s performance was controlled and minimal. Mostly she focused on the central image, occasionally rising from the bench and moving closer to the screen, as if attempting to touch the wallpaper, or else adjusting the size of the image shown by manipulating the projector. At the crescendo of the images and sound she lay on the stage, with her back to the audience, as if overcome by fatigue or inertia.

Concerned with the representation of women, creativity, madness, identity and self-discovery, in Faded Wallpaper Keane explored these issues through an immersive experience comparable to the psychological episode narrated in Perkin-Gilman’s novella. The visual and aural elements of the work created an onslaught of images and voices which, rather than exposing a clear narrative, intersected creating an overwhelming experience, simulating the loss of identity, and the struggle to recapture the self. While the footage of the peeling wallpaper and the text played over the audio track directly related to the story, Keane’s slow, minimal movements represented something quite different. It showed up a sense of creative paralysis in the onslaught of images of women circulating through the video.

Although Keane was captivated by the surreal and absurd images that flashed before her, she was powerless to remove the wallpaper and uncover the final, complete image. The most she could do was reach out to the screen, or adjust the size of the image, manipulating what was there, but never creating anything new. Rather than addressing her audience face-on, she deliberately positioned herself in alignment with them, facing the projection, reinforcing their own position of powerlessness against what played out in front of them. The performance, then, did not just depend on the interaction between performer and video, but relied on the immersive experience shared by the performer and the audience, created by the intersection of video, audio and live body within the shared multi-media space.

Acatia Finbow

May 2016