Fig.1

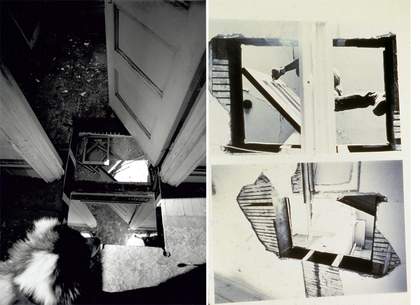

Gordon Matta-Clark

Bronx Floors: Threshole 1972

2 black and white photographs

Each 356 x 508 mm

© ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

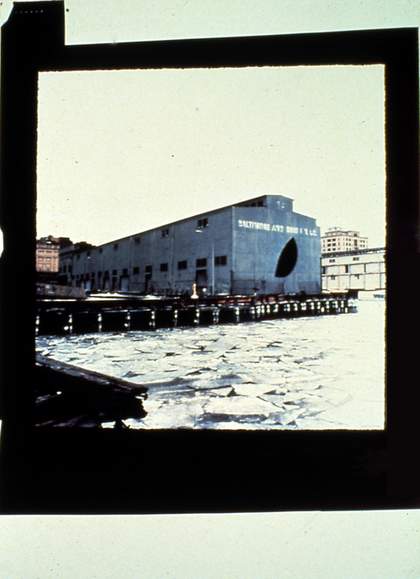

‘Architecture is always dream and function, expression of a utopia and instrument of a convenience’, wrote Roland Barthes in The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies. In this paper I wish to explore the way in which the language of modernist architecture and the dreams embedded within it impacted on the work of Gordon Matta-Clark (1943–1978). Unusually among artists of his generation, Matta-Clark was trained as an architect at Cornell University, where he was taught by some of the most eminent architectural theorists of the era and from where he graduated with a BArch in 1968. Recent scholarship reveals him to have been a far from indifferent student.1 His subsequent career as an artist was brief, cut short by his death from cancer, aged only thirty-five. He is best known for those works in which he dissected existing buildings, slicing into and opening them up, using the simplest of means and converting them into gravity-defying, profoundly disorientating walk-through sculptures. These varied in scale from the cuts he made in abandoned tenements in the Bronx to create a series of works called Bronx Floors: Thresholes (fig.1), his iconic rearrangement of a suburban house in New Jersey known as Splitting (fig.2), and the majestic, temple-like space he created in a New York waterfront pier known as Days End (fig.3). The sheer drama of these and other projects carried out in France, Italy and Belgium has often led to the assumption that through them Matta-Clark was expressing his hostility to architecture and rejection of his early training. In fact, although he described studying at Cornell as ‘his first trap’,2 what he learnt there provided the fuel for an ongoing internal dialogue, and was as much the material of his practice as the bricks, mortar, floorboards and steel of the buildings he operated on.

Fig.2

Gordon Matta-Clark

Splitting 1974

Colour photograph

680 x 990 mm

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, GMCT1051 © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

One piece in particular, the collaborative exhibition known as Anarchitecture (1974), reveals something of this ongoing mental wrestling-match with architectural discourse. As with so much of Matta-Clark’s oeuvre, the piece has an importance beyond its material manifestation, not least through the coining of a word used in many contexts with reference to Matta-Clark. Before proceeding, therefore, we have to gain some kind of purchase on the term Anarchitecture, the precise meaning of which is elusive, appearing to shift depending on its user. Are we simply referring to the exhibition of that name staged at 112 Greene Street in New York in March 1974? Are we also thinking of the meetings held by the loose collection of friends and collaborators calling themselves the Anarchitecture Group that took place over the previous year? What about those surviving works by Matta-Clark that clearly relate to the concept for the exhibition Anarchitecture and were probably intended for inclusion but never made it past the group selection process? The artist himself used the word in different contexts both before and after the show, in interviews and in his notebooks. Since his death it has become closely associated with his wider ideas about art and architecture; indeed, some would probably argue that it has been hi-jacked by those seeking to foreground their own agenda. Finally, if Anarchitecture was originally the title of a collaborative exhibition, how comfortable should we be with the way it is now used almost exclusively in connection with Gordon Matta-Clark? The surviving artists who took part in the development and staging of the show have continuing careers and their own ideas about what it all meant. The ‘re-staging’ of Anarchitecture as part of the exhibition Open Systems (2005) at Tate Modern triggered numerous questions relating to the work’s authorship and content. At the simplest level, the memories of surviving participants differed as to what had and had not been included. The original installation had not been documented, and in such a situation the first question that the exhibition needed to attempt to answer became whose memory is it that is being reconstructed?3 Meanwhile, the passage of time and the accruing of financial value in the work itself raised questions about whether the material could be safely exhibited in the informal manner it had been at 112 Greene Street. However problematic these issues may have been for those engaged in organising or lending to the exhibition, it seems somehow fitting that a piece gestated through freewheeling discussions in the lofts and bars of SoHo in the early 1970s should continue to generate heated debate, dissension and hilarity three decades later. I make no apology for concentrating as much on the artist’s writings and on the way the concept of Anarchitecture informed his wider practice as on the 1974 show, the exact content of which is still the subject of dispute.4

Fig.3

Gordon Matta-Clark

Day’s End (Pier 52) (Exterior with Ice) 1975

Colour photograph

1029 x 794 mm

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, GMCT685 © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

Those listed as participants in the Anarchitecture Group in 112 Greene Street Workshop,5 the book that is the best record we have of what went on at Jeffrey Lew’s artist-run space, were Laurie Anderson, Tina Girouard, Suzanne Harris, Jene Highstein, Bernard Kirschenbaum, Richard Landry, Gordon Matta-Clark and Richard Nonas. This loose grouping, that included artists, musicians and dancers and even, in Bernard Kirschenbaum, an experienced architect, met over the period of around a year. Attendance, location and timings varied; membership was informal. The origin of the word Anarchitecture itself equally evades pinning down. While those who attended the meetings have generally attributed it to Matta-Clark, surviving participants also sometimes remember it as having been arrived at collectively; a combination of ‘anarchy’ and ‘architecture’ stumbled across through group discussion.6 Whatever its origin, the term Anarchitecture, expressing as it does a creative tension between Apollonian and Dionysian opposites, has come to summarise many of the concerns explored by Matta-Clark during his brief career.

Once a date had been fixed for the exhibition, Matta-Clark proposed that each of the group should provide black-and-white photographs in the same 16 x 20 inch format, developed and printed in the same darkroom and then exhibited anonymously, under the group name. Naturally, these rules were broken immediately, with participants making collages, word pieces and employing fabric, sound and a heat-lamp among other media. A selection of images from the Anarchitecture show were published in June 1974 in Flash Art Magazine, the combination of exhibition and art world publication a classic formula for the announcement of the birth of a new movement – one thinks of the article by Germano Celant in Flash Art in 1967 that announced the birth of Arte Povera. While it is unclear how many people actually saw the exhibit during its display at 112 Greene Street – very few, seems to be the most likely answer, with Matta-Clark telling an interviewer regretfully that it ‘never got strongly expressed’7 – Anarchitecture served its purpose in terms of laying down a marker in the wider art community, and as a launching-pad for Matta-Clark’s ideas. He was well versed in such art-historical strategies; after all, his own father, the Chilean surrealist painter Roberto Matta, treated every interview and exhibition catalogue as an opportunity for polemical and philosophical discourse. The Anarchitecture show, then, was a kind of manifesto; but a manifesto of a tendency that never existed, a temporary alliance of creative spirits that inhabited the same moment in history. A manifesto, perhaps, for a generation disillusioned with manifestos. Or, as Caroline Gooden put it, ‘Anarchitecture was a work in progress in Gordon’s mind’.

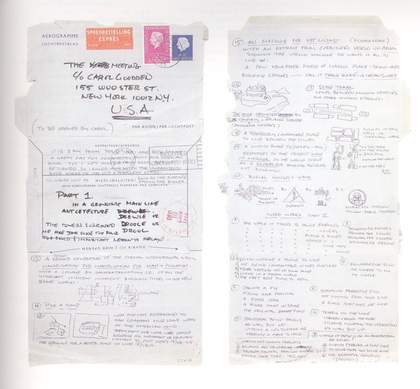

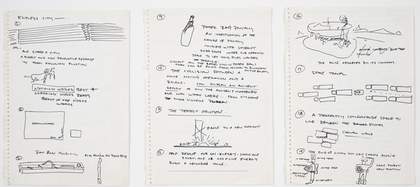

Fig.4

Gordon Matta-Clark

Letter to Carol Gooden/The Meeting, December 1973

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, on deposit at the CCA, Montreal.

© ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

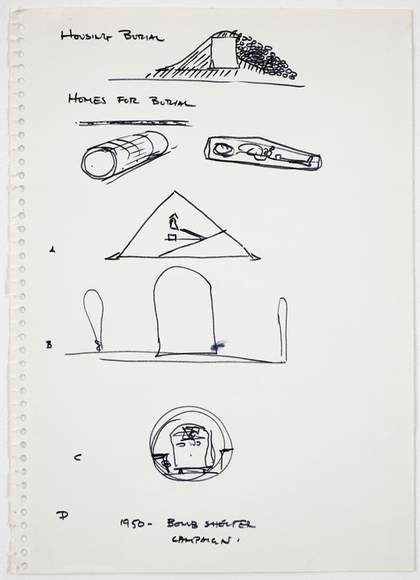

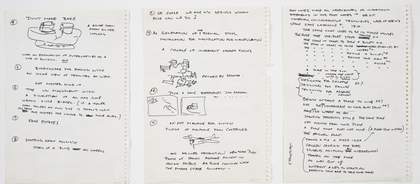

That his mind was brimming over with ideas was evident from the letter he sent to the Group with proposals for what should be included in the exhibition (fig.4).8 Characteristically, it is a document marked by humour, adventurous spellings and surrealist flights of fancy and wordplay. Equally characteristically, closer inspection reveals it to be firmly grounded in the writings of the giants of European modernism and design that he had studied at Cornell, particularly the French artist and architect Le Corbusier. Through a process of linguistic reversal, a favourite philosophical tool, he uses these writings as a springboard to launch himself in a different direction and arrive at new starting points for his own explorations. The version of Anarchitecture imagined in the letter is a far cry from the disciplined, photography-based exhibition he proposed later. His methodology is made explicit from the start. The first object he suggests for inclusion is a plain board with the words ‘NOTHING WORKS’ written on it. This fundamentally anti-functional statement, described in his letter as ‘a reaction to the prime-crime axium of modern design-fighters’, stands in direct opposition to the whole ethos of utilitarian modernism. At the same time it approaches the life-experience of inhabitants of downtown New York in the early 1970s, as the city approached bankruptcy and garbage piled up on the streets. In a footnote, Louis Sullivan’s dictum ‘form follows function’ is manipulated through the distorting mirror of the artist’s compulsive punning to become ‘form fallows function’. If this wordplay means anything it implies that a rigid adherence to certain ideas of form will restrict an object or a building’s usefulness. An opposite approach might be to allow an object’s appearance to suggest spontaneous new uses, in the way that the carriage of a wrecked train suddenly becomes a bridge in the photograph included in the Anarchitecture show (fig.5). Further on in the same letter, Matta-Clark makes explicit his relationship to Le Corbusier, by suggesting another idea for inclusion: ‘AN MACHINE FOR NOT LIVING WITH AN EXTRACT FROM CORBUSIER’S VERSO UN ARCHITEC (edge of paper destroyed) SHOWING THE VIRGIN MACHINE HE WANTS US ALL TO LIVE IN.’

Fig.5

Untitled (Anarchitecture) 1974

Photograph mounted on board

406 x 559 mm

© ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

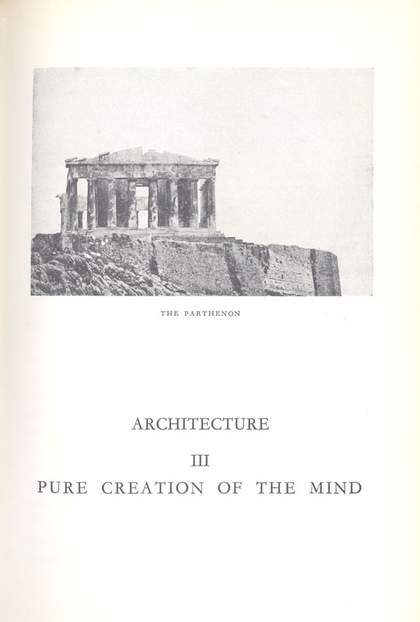

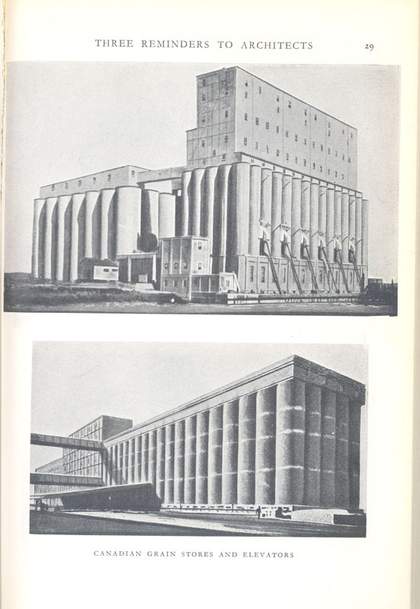

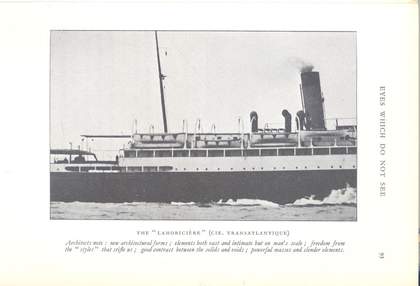

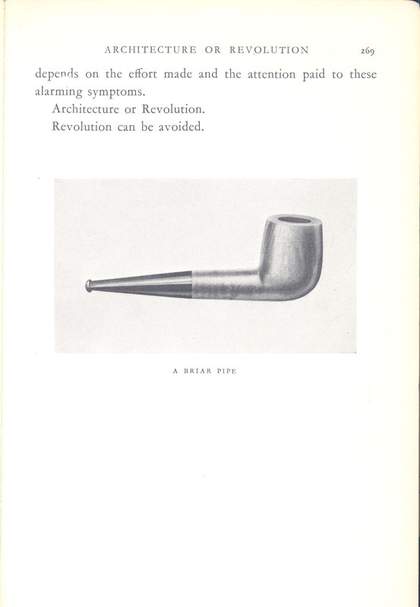

Since the 1930s, the ideas of Le Corbusier had made a tremendous impact in America, not only in the architectural schools but also in planning departments up and down the nation. City planners eagerly adopted the model offered in La Ville Radieuse, in which congested streets and tenements are replaced with a combination of towers and free-flowing expressways. Vers Une Architecture, first published in French in 1923 and (incorrectly) translated as Towards a New Architecture in 1927, was required reading for any architectural student of Matta-Clark’s generation and fundamental to the teaching he received.9 Colin Rowe had long used the book in the course he taught comparing Le Corbusier’s ideas to Palladianism, pointing out that, just as in the case of the Italian architect, and despite the legacy he had left behind of iconic buildings, Le Corbusier’s influence had ‘been principally achieved through the medium of the illustrated book’.10 In the collection of polemical essays contained in Vers Une Architecture, Le Corbusier attempts a radical synthesis of the classical perfection of the Parthenon and the design aesthetics of the machine age. The same process applied by engineers to the design of the latest aeroplanes and ocean liners should guide architects, he argues, in creating housing schemes and planning cities. The inefficient and unhygienic structures of the past should be thrown on the scrap heap, just as a workman discards an outmoded tool. The city itself should be orderly and legible, ancient housing stock replaced with arrangements of mass-production housing. The text has a poetry, a rhythm of its own, creating a momentum as it moves towards its conclusions that must have been seductively hard to resist in the pre-lapsarian days of high modernism. It is illustrated with black-and-white photographs, taken from Le Corbusier’s extensive collection of press-cuttings and images of the Parthenon (fig.6), of industrial buildings, Canadian grain elevators (fig.7), racing cars, aeroplanes, steam ships (fig.8), and even a briar pipe (fig.9). The text is punctuated with aphoristic statements, some of them repeated again and again, like modernist mantras, with a quasi-religious intensity: ‘The Plan is the generator. The house is a machine for living in. Do not forget the problem of architecture. The problem of the house has not been clearly stated.’11

Fig.6

From Towards a New Architecture by Le Corbusier, translated by Frederick Etchells 1927, published London 1948, reprinted 1974, p.185

© FLC/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2007

Fig.7

From Towards a New Architecture by Le Corbusier, translated by Frederick Etchells 1927, published London 1948, reprinted 1974, p.29

© FLC/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2007

Fig.8

From Towards a New Architecture by Le Corbusier, translated by Frederick Etchells 1927, published London 1948, reprinted 1974, p.93

© FLC/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2007

Fig.9

From Towards a New Architecture by Le Corbusier, translated by Frederick Etchells 1927, published London 1948, reprinted 1974, p.269

© FLC/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2007

It is not insignificant that in the hands of Matta-Clark, the title of Corbusier’s work becomes Verso un Architecture. To read Le Corbusier’s seminal text when you have also studied the letters, notebooks and interviews of Matta-Clark is to experience what we can call, for lack of a better term, reverse echoes: there is no doubt as you turn the pages that you are in the presence of an important influence on the artist’s thinking. Almost every one of the French architect’s key statements finds its opposite in the writings and the practice of the American artist. ‘Do not forget the problem of architecture’, wrote Le Corbusier. ‘Anarchitecture attempts to solve no problem’,12 wrote Matta-Clark in one of the poetic and ambiguous statements in his notebooks. (In these words one hears an echo, impossible to verify, of Marcel Duchamp’s statement, ‘Il n’y a pas de solution parce qu’il n’y a pas de problème’, and beyond it to the concluding remarks in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus).

Matta-Clark once told an interviewer that, far from addressing humanity’s problems, most architects were not ‘solving anything except how to make a living’.13 Yet it was not just a question of attacking architects or architectural theories. Matta-Clark writes in one of his notebooks that, ‘Design morality is valid. The functional issue was chosen because it seemed the most critical break from the beaux-arts, histrionic garbage. It was valid for its time. But how long has it been? Seventy years since any kind of radical reappraisal has gone on?’ It was the dead hand of such figures as Le Corbusier on American creativity that Matta-Clark resented. Yet the passionately held tenets of those he jokingly referred to as ‘The International Stool’ could be turned in an intellectual judo-move and used to develop his own conceptual framework. This was a game that could provide real results. With the help of his fellow travellers Matta-Clark was carving out a territory within which to work. Anarchitecture, with its use of found photographs and the aphoristic statements Matta-Clark recorded in his notebooks, is on some level both an echo of and a riposte to Corbusier’s polemic.

In the interest of balance, however, it is important to state that Le Corbusier was attacked by some critics in the 1920s for not being functionalist enough and that he later adopted a more clearly dualistic position, expounded in Défense de l’architecture (1929), opposing those who took the functionalist aspects of his philosophy to an extreme that excluded all considerations of the spiritual or the aesthetic. Nonetheless, it was the absolutist aspects of Le Corbusian town planning that were often most enthusiastically adopted in the United States; nowhere more so than in the city of New York, which under the leadership of City Planning Commissioner Robert Moses led the nation in exercising compulsory purchase powers under Title 1 legislation,14 razing slum tenements, erecting high-rise social housing and extending expressways into the heart of the urban fabric.

Even before he went to university, Matta-Clark had lived through a visceral encounter with exactly these ideas. A resident of Greenwich Village from the age of six until he left to take up his studies at Cornell, he lived originally on La Guardia Place, until it was taken over by New York University, and then at 107 West 11th Street, between 6th and 7th Avenue. He referred to the area with affection in interviews and correspondence, describing himself as a Native New Yorker, and speaking of the importance that living in an apartment and meeting neighbours from his window high above the ground had had on his artistic development. It was a period of extraordinary change in the neighbourhood, with the artisan workshops, bohemian tenements and small businesses that the area was famous for being knocked down and replaced with enormous residential and office blocks. Matta-Clark would have grown up surrounded by construction sites; a map of the area from the New York Times in December 1957 showing developments under way locates one of the largest right on his doorstep. This was the ‘metamorphic New York’ described by Saul Bellow in his novel Herzog, through which his eponymous hero wanders, surrounded by the burning pyres of torn-down buildings, his clothes and those of his fellow pedestrians streaked with ever-present ash. Aware as he must have been of the street-drama of the construction and demolition going on around him, motifs that came to play a part in his own practice,15 Matta-Clark would have been equally aware of the argument raging in the neighbourhood in which he lived. The community fought a long battle against the plans of Robert Moses to drive the Fifth Avenue Extension through Washington Square Park, the much-cherished centre of the neighbourhood. The Park had long functioned as a much-needed refuge from the noise and heat of city streets, as a play area for children and a place where chess tournaments and local art exhibitions were held.16 Moses’ plan galvanised the community. A new political party, the Village Independent Democrats, was formed, a fusillade of letters and opinion pieces launched and many stormy public meetings held. The New York press, already outraged at the proposed destruction of over forty acres of the Village, took up the campaign. The Village Voice, which was to play a vital role in the campaign, was born in 1955, at the height of the protest. Thirty thousand local residents put their signatures to petitions printed up by the Washington Square Committee; one of these petitions, displayed in the exhibition Robert Moses: Remaking the Metropolis,17 carries the signature of Lleandra Lewis who lived at 259 West 11th Street, down the street from the Matta household, demonstrating how close the protest came to their own apartment building. When, in the spring of 1959, in view of the strength of feeling expressed within the community, the Board of Estimate voted to close the Park to traffic permanently, even banning the buses that had previously used it as a turning point, the Voice carried the story on its front page under the headline ‘Victory Won’.18 Locals held a celebration in the Park and burnt a car in effigy.19

Matta-Clark arrived in the city a decade later, after completing his degree in architecture and spending a further year living in Ithaca, assisting on the seminal Earth Art show staged at the University and working for the architecture department in the nearby city of Binghamton. He took up residence a few blocks away from his childhood home in SoHo, where the artistic community had been defined and radicalised by the successful struggle against another Moses plan, to join Brooklyn and New Jersey with the 10-lane Lower Manhattan Expressway (LoMEX), a project that would have wiped the loft-dwellers off the map. SoHo artists gained a political education along the way, through the alliances they formed with residents of the Chinese and Italian communities, with veterans of the struggle in the Village, with cast-iron façade preservationists and urban theorists of the decentralised, neighbourhood based city. The writings of Jane Jacobs in particular would have been known to Matta-Clark while he was a student at Cornell and were increasingly influential, legitimising as they did the idea of the densely packed neighbourhood and proposing that more could be learned by closely observing the urban environment as it was than imposing grand plans upon it.20 This was the ‘mind wind’, as Buckminster Fuller would have put it,21 which was blowing in the streets that gave birth to Anarchitecture.

There was another connection between Matta-Clark and Le Corbusier. His father, the Chilean surrealist painter Roberto Matta, had worked as a draughtsman in the architect’s studio in the late 1930s, at the time Le Corbusier was developing his plans for La Ville Radieuse. As has been frequently reported, he rejected his employer’s ideas, proposing in an article in the surrealist journal Minotaure22 an apartment with walls ‘like wet sheets that change shape to fit our psychological fears’, furnished with biomorphic couches that appear in his illustrations to mould to and at the same threaten to swallow the human body. Jane Crawford, Matta-Clark’s widow, maintains that Matta père, an intermittent but influential presence in his son’s life as he grew up, ‘always railed against Corbu’, and that Gordon would have followed suit.23 Perhaps more importantly, Matta provided a model of an artist who saw himself as a philosopher as much as a visual draughtsman, someone who took great care over the statements he made in interviews and in the publications that accompanied his exhibitions, coining new terms for areas he opened up in his art practice. As the curator Joanna Drew wrote in one such catalogue, ‘Matta says that he is not a painter but this statement is not as unambiguous as it might appear. Among other things he means that he is not only a painter; his painting language and the many other (verbal) languages he uses serve his dynamic inventiveness … He invents words with the same freedom that he invents images and they at once take on their own independent life.’24 Words used to describe the father that could equally be applied to the son.

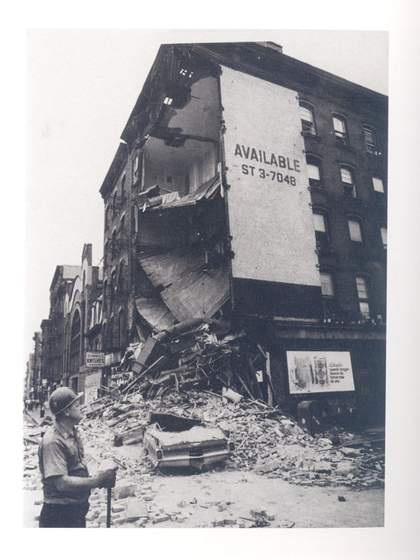

The starting point for the Anarchitecture exhibition proper was a linguistic one. The members of the group, once they had settled on the term Anarchitecture, made a series of puns and wordplays upon it, in a freewheeling and tequila-fuelled discussion; Tina Girouard wrote these down, and the resulting list formed a key piece in the show (fig.10). Remembering the process of creating the list, Richard Nonas explained, ‘The interesting thing about Gordon was that he was full of ideas and in a way highly intellectual. But, just in the same way that he broke context, he broke words and ideas. So he was playing with it, playing with the intellectualising, so this is a perfect … Gordon thought process right here on the wall … he did it almost as a form of analysis, you know. That was his theoretical position, that you could deal with ideas in that way.’25

Fig.10a

Image from Anarchitecture 1974

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

Fig.10b

Image from Anarchitecture 1974

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

Fig.10c

Image from Anarchitecture 1974

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

A number of the found photographs included in the Anarchitecture Show are of buildings mutated through various natural and unnatural disasters, echoing the aims Matta-Clark had written on a note card:

A RESPONSE TO COSMETIC DESIGN

COMPLETION THROUGH REMOVAL

COMPLETION THROUGH COLLAPSE

COMPLETION THROUGH EMPTINESS26

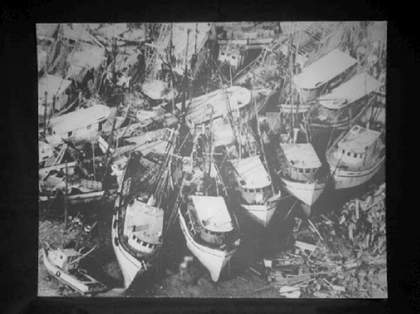

Fig.11

Photograph from Anarchitecture 1974

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

What are these images suggesting? Firstly, they are not meant to be read literally. On a metaphorical level they represent the opposite of the harmonious structuring of society and the urban environment that Le Corbusier believed was the highest aim of civilisation. Anarchitecture celebrated the inner city in all its disorder and variety and crazy juxtaposition of eras and styles (fig.11). The forces of nature that picked up boats and piled them on top of one another both suggested new types of structures and alluded to the densely packed fabric of the inner city (fig.12). The gas explosion that removed the side of a building, exposing its inner framework, broke down the strict privacy and property codes that dominated city life. On one level, the sign still affixed to the wall that declares space ‘Available’ (fig.13) is grimly humorous. On another, the building’s interior is indeed available in new ways; to the onlooker, who is granted a different vista; and to those who could now walk in if they chose, untroubled by exterior boundaries.

Fig.12

Photograph from Anarchitecture 1974

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

Fig.13

Photograph from Anarchitecture 1974

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

If Matta-Clark felt free to employ this imagery free of any personal or tragic overtones, he had earned the right to do so. In his notebooks a dated entry with an unusually autobiographical tone is set among explorations of the themes that informed Anarchitecture. ‘Tonight August 3rd 1973 my only known cousin died in an incredible way’, he wrote. ‘His talk on the phone with his mother was interrupted by “the ceiling’s falling” … He and his wife were living in the Broadway central that was demolished by an unknown force making it collapse instantly without warning. All around the accident the city assembled its emergency gear. Crowding and hysteria dissolved into a reaffirmation of immediate disintegration.’ Despite this personal connection with the random forces of destruction pictured in the photographs submitted to the Anarchitecture exhibit, Matta-Clark’s interest in the imagery remained primarily an aesthetic and philosophical one. He had long been fascinated by glimpses of the interiors of buildings, whether seen through a window or through the work of the wrecking-ball, as in the series of photographs he took of the exposed walls of semi-demolished buildings that became Wallspaper 1972 (fig.14).

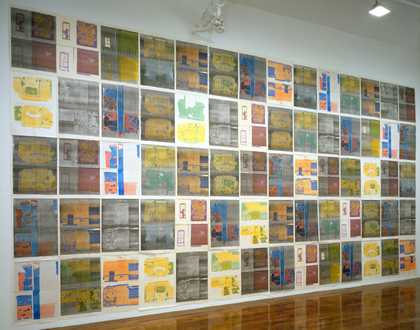

Fig.14

Gordon Matta-Clark

Wallspaper Installation 1973

Multiple copies of colour offset prints

72 sheets, each 873 x 568 mm

Installation dimensions variable

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, GMCT2390 © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

As an artist, he was fascinated by the ever-changing face of the city. His inclusion of a photograph of the World Trade Towers in the Anarchitecture exhibition – an image that characteristically focuses on the space between the towers rather that the towers themselves – reveals something of the mix of attraction and revulsion he felt for the giant structures that would have slotted neatly into the business districts of Corbusier’s Contemporary City or Plan Voisin de Paris. While Matta-Clark was a student at Cornell he spent a semester based in New York and was taken regularly with other students to study the Twin Towers as they were built. In May 2001 I took a snapshot (fig.15) standing outside 112 Greene Street (on left), to remind myself of the impact the Towers must have had on Matta-Clark and his friends in the Group as they gradually climbed the sky. In a proposal Matta-Clark sent to Robert Ledenfrost in January 1975, in which he described himself as a representative of The Anarchitecture Group, there is a sketch inscribed ‘the importance of an event such as the world trade centre is the sum total of its oversights’. Once again perhaps we can detect a Matta-Clark pun: the oversights he is referring to are not just the colossal waste and expenditure involved in the construction and maintenance of such a project but the viewpoints the tower offers of the city. SoHo, an area of near autonomy, seemingly beyond the control of city planning regulations, was, once the towers rose above it, overseen by their vertiginous façades. It was as if the world of finance was prophetically reasserting its dominance over the bohemian mini-state at its feet. Matta-Clark’s letter to the Group features a drawing of the Towers cancelled out with a bold cross and the caption ‘Erase all the Buildings on a Clear Horizon’.

Fig.15

Photograph of the Twin Towers, New York 2001

© James Attlee

Beyond this, the power of Towards a New Architecture was largely due to its combination of image and text, its revolutionary design refined during the original publication of the essays in the pages of the journal Esprit Nouveau. Le Corbusier was bringing a magazine aesthetic to the book, allowing the images to have a separate and distinct life to his words. The images had to be countered directly, Matta-Clark forced to become as avid a rummager through press cuttings as the Swiss architect himself – hence Le Corbusier’s already touchingly dated steam-powered ocean liners are rebutted by an image of a sinking ship upended, disappearing beneath the waves. In a notebook Matta-Clark proposed that Le Corbusier’s beloved aircraft should also be pilloried:

A NOT MACHINE FOR LIVING

PICTURE OF AIRPLANE FROM LE CORBUSIER

AND AIRLINER DESTRUCTION

NEW YORK POST

PHOTOS OF FAMOUS AIRPLANE ACCIDENT IN

HOUSING PROJECTS. AIRPLANE COLLISION WITH

THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING 27

‘The Plan is the generator. The Plan proceeds from within to without’, Le Corbusier had written. He saw adherence to the Plan as essential to avoiding what he termed ‘wilfulness’ on the part of the architect. In contrast, Matta-Clark was open to inspiration through the operation of chance events: the rings left by a teacup on a sheet of paper suggested the complex plan for the work Office Baroque he once told an interviewer. ‘If needed we work to disprove the common belief that all starts with the plan’, he wrote in one of his notebooks. ‘There are forms without plans – dynamic orders and disorders’.28 ‘A mass is enveloped in its surface; Contour and Profile are the touchstones of the architect’, Le Corbusier insisted. Matta-Clark, on the other hand, declared himself ‘sick of the surface formalism’ he had been taught at Cornell.29 His journey was in the opposite direction, opening up structures to light and air and burrowing beneath the surface of the street to explore, photograph and film the catacombs, sewers and viaducts concealed there. One of his proposals in his letter to The Meeting is for a ‘rat run city a steel dwelling for rats with a handy handle for commuters who prefer their own rats wherever they go.’ Since the Renaissance, animals, apart from horses and domestic pets, have largely been excluded from the city in the West. At the same time a vast rodent population inhabits the underground, usually encountered by human city-dwellers only in dark alleys and abandoned buildings, their threatening, reflective eyes caught in the beam of a torch in genre movie scenes, always signifying a moment of vulnerability for the protagonist. Many writers, from the seventeenth-century Robert Burton to Sigmund Freud in Civilisation and Its Discontents, have compared the workings of the city (and the state) to that of the human mind. In carefully controlled modern urban environments, the unseen regions underground can be taken to represent the subconscious, from which, on occasion, spill out the repressed memories and unlawful impulses, as it were, of the metropolis. Matta-Clark was taken on tours of the Paris sewers as a teenager when he went to spend time there with his father’s wife and family. When he returned as an adult, they explored further, going on tourist visits to the catacombs. These spaces appear in the film Substrait and the photographic montages derived from it, in which Matta-Clark juxtaposes images of neatly stacked skulls with racks of wine bottles stored underground, wittily making the observation that in French culture the dead are arranged as neatly as vintage wine. (The dead, of course, like wine, are also changed by the passage of time, increasing in value and significance or turning back into mere organic matter). Malitte Matta remembers that when he returned to Paris as an adult his explorations took him beyond the tourist agenda. ‘There was a very famous underground complex that had been basically, I think, constructed during the French Revolution, and which had been transformed by the Germans into a kind of bomb shelter headquarters during the Second World War and this place had been supposedly completely sealed off. But of course, all of the bums in Paris knew about it and when the students got into trouble in their own uprising in ’68, the bums showed the students how to get around under … So Gordon was in on all of that. That interested him very much … he was really very much interested in this idea that the city had a life which was in the air, it had a life which is on the ground and it had a life below the ground. And I think he intended to do something much more important with all of this. I think the things that we see today were sort of notes he took. I think he was wanting to do something with that material.’30

One of Le Corbusier’s prime aims was to abolish the hidden infrastructure that lay beneath the streets, along with its unofficial inhabitants, making conduits for all services easily accessible. In contrast, Matta-Clark saw the underground as one of the last repositories of history in North America that had not disappeared under parking lots, and worried that it was now under threat from the ever-deeper foundations of new buildings. Working within the influence of the surrealist tradition, he celebrated the unconscious, the irrational in the urban environment. When the forces of control break down – most noticeably in the case of 1970s New York, the garbage disposal services – the rat, a denizen of the underworld, emerges into the light of day. Instead of causing us to recoil in horror, Matta-Clark suggests with dark humour, the rat, along with the shadowy unexplored regions it inhabits, should be cherished. Le Corbusier saw the architect as being in a fruitful collaboration with the captain of industry in an alliance of elites; one creating the materials and the other the plans from which to build the future. The architect was required, he wrote, ‘to realise an order that is a pure creation of his spirit … a well-mapped-out (housing) scheme, constructed on a mass-produced basis, can give a feeling of calm, order and neatness and inevitably imposes discipline on the inhabitants’. Here we are given a glimpse of the more worrying political implications of Le Corbusier’s thinking; in order to realise his vision, the architect becomes drawn in to maintaining civil order. He saw the city as a whole, not as a series of neighbourhoods; only a master architect invested with authority by the state could deliver the vision required to re-shape the city. It was this legacy he bequeathed to American cities through his influence on planners like Robert Moses, who had a clearly defined plan for how he wanted to change New York, combining better road access with a greater number of public parks and open spaces created by razing ‘slums’ and re-locating the poor into vertical high-rises. When asked why he persisted in his arduous multiple planning roles for the City when he could have made more money in the private sector, Moses replied: ‘I made up my mind long ago to get my reward from tangible accomplishments, from the dogwood, the tulip, the chrysanthemum, the curving pathway, the spiderwork of suspension bridges, the reclaimed waterfront, the demolition of slums, the crunch of a baseball bat and the shouting of children in playgrounds’.31 To achieve this utopia, any means were permissible. As the journalist and fair housing advocate Robert Starr put it, ‘Moses really believed people could be moved around as easily as automobiles’.32 Matta-Clark and his loft-dwelling friends in SoHo had little sympathy either with governmental interference or the grandiose visions of the master-architect; they fitted a different model, described by Buckminster Fuller when he said ‘all human progress is made in the outlaw area’.

Many of the participants in the Anarchitecture exhibition had come to SoHo in search of affordable living and working spaces and had ended up converting post-industrial workshops into live-in studios. Slicing up and re-building these apartments, both for himself and for others as a way to earn a little cash, was one of the ways Matta-Clark developed his ideas about the sculptural use of space. As he put it, ‘one of my favourite definitions of the difference between architecture and sculpture is whether there is plumbing’.33 The SoHo loft-dwellers’ lifestyle fostered self-reliance and creativity and obviated the necessity for a master-architect. In this sense, the Modernist programme could be said to be about control, while the SoHo experience was about the freedom to find a new way of inhabiting the city. An over-complicated modernist dwelling with high specifications of luxury both dis-empowered its occupants and became instantly outdated, unable to shift shape with the changing demand of those who used it. Such a house is, as Matta-Clark stated in his letter to the Anarchitecture group, ‘obsoleted by its comforts’. Le Corbusier presented a choice in Towards a New Architecture between Architecture and Revolution. For the generation living in SoHo in the early 1970s the revolution had already happened. The way people lived had evolved, rendering the rigid structures of modernist architecture irrelevant. As Matta-Clark put it on a note card: ‘A PRIMARY ARCHITECTURAL FAILING A SYSTEMATIZED CONSISTANT APPROACH TO A WORLD OF TOTAL “WONDERFUL” CHAOS.’

A further contrast between the thinking of the two men lay in their attitude to the local, the small-scale and the vernacular in architecture. Le Corbusier and his colleagues on the CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) were strictly international in outlook; styles, he wrote, were a lie. Matta-Clark, on the other hand, regretted the lack of a distinctly American architectural vocabulary; in a notebook he wrote that ‘America has no forms all its own’ except distortions of European monumentality, the billboard and ‘the tragedy of an exterminated native population’.34 As he made clear in his letter to the group and in other writings, he was fascinated in what he called the non-monumental, or non-u-mental. The architectural aims of the group, he told an interviewer, had been more elusive than doing pieces that would demonstrate an alternative attitude to buildings. ‘We were thinking more about metaphoric voids, gaps, leftover spaces … for example the place you stopped to tie your shoelaces’. These were the places ignored in the architectural master plans and often inhabited by people who were similarly ignored by the system. Matta-Clark’s notebooks contain detailed observation of the bums and derelicts living on the streets of Manhattan.35 In his letter to the Group he suggested the show should include A Review of Hovel Homes – and he did put forward a photograph of a street person’s shelter for inclusion. This interest was further expressed in the series of photographs he took of small houses and shepherds’ shelters in the hills around Genoa when on a walking holiday with Jane Crawford and of self-built shanties in the West Indies. His ideas about art and architecture were directly about the body, about changes that could be made to structures by the physical actions of a single human being.

If, as Thomas Carlyle had written a century and a half earlier in Sartor Resartus,36 clothes could be ‘a warm movable house, a body round thy body’, then architecture could be as flexible and movable as clothing. Sometimes architecture could be the body itself, giving shelter to the unborn, as in the photograph of a naked pregnant woman he proposed for inclusion in Anarchitecture; sometimes it housed the body after the spirit had departed, as in the images he proposed of graveyards.

Fig.16

Gordon Matta-Clark

Window Blowout 1976

Photograph mounted on board

406 x 559 mm

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, GMCT3025 © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007

Both Matta-Clark and Le Corbusier shared a fascination with the way buildings act on human consciousness – the interplay, perhaps, between the elements Barthes identified within architecture of function and dream – and also in the attitudes that might give rise to new building types. ‘The right state of mind does not exist’, Le Corbusier told his readers in Vers Une Architecture in 1922. ‘The state of mind for mass-production houses, the state of mind for living in mass-production houses, the state of mind for conceiving mass production houses.’ By the 1970s that state of mind had been tried, tested and expressively rejected by the inhabitants of the vandalised modernist housing projects Matta Clark captured in the photo-piece Window Blow-out (fig.16). Matta-Clark himself was more interested, as he put it in his notebooks, in converting a building into a state of mind. This involved liberating structures from the straightjacket of their maker’s intentions and recycling them as consciousness-altering artworks – ‘making sculpture’, as he wrote in a letter to the New York Department of Real Estate, ‘using the by-products of the land and the people’. The effect achieved in the large building cuts could be mesmeric. When he moved from floor to floor in the Parisian work Conical Intersect, he told Lisa Béar, his ‘normal sense of gravity was subverted by the experience. In fact when you got to the top floor and looked down through an elliptical section through the floor that was cut out, you would look down through the fragments of a normal apartment space, but I had never seen anything like it. It looked like … almost as though it were a pool. That is, it has a reflective quality to it and a surface – but the surface was just the accumulation of images of the spaces below it.’37 It is worth remembering that for Matta-Clark’s generation of New York artists, copious drug and alcohol intake and the accessing of other forms of consciousness through meditation techniques and ritual were a part of everyday life. It may be that such experiences fuelled an ambition in Matta-Clark to create artworks that triggered reactions in the viewer beyond the normal, somewhat restricted aesthetic frisson available to the gallery-goer. To record these temporally limited artworks required him to create an architecture that existed in a different space and time; the photographic collages and films he has left behind are constructed, piece by piece, from architectural elements. For his collages, slide positives were sliced and spliced on the light table and then blown up as large-scale Cibachromes, the change in scale reminiscent of the one from architect’s model to construction site; the film camera moves through a building, revealing depth, space and the passage of light, along with the progress made by power-saw, lump hammer and chisel, humble tools by which human-beings are able to penetrate solid matter. In this way Matta-Clark created an architecture in two dimensions that still manages successfully to give the viewer access to a vanished three, or arguably four, dimensional experience.38 Just as the influence of Le Corbusier penetrated global consciousness principally through the pages of a book, it is the writings, photographs, drawings and films that continue to disseminate Matta-Clark’s vision today. Anarchitecture was, as he wrote on an art card, ‘about making space without building it’. At the same time, those ideas of Matta-Clark’s that could be termed more directly architectural worked from the bottom up, in a reversal of the usual pattern of the architect-client relationship. By observing the lives of those who were forced to live on the street, as he put it ‘beyond between and without walls putting to waste the most presumptuous building plans’,39 he came up with prototype forms, free of any commodity value, which could be used by anyone to create a shelter. The work Garbage Wall(fig.17), created three times during his lifetime and several times using his instructions since his death, combines a frame of chicken wire, concrete and rubbish collected on the street. On one of the art cards on which he obsessively drafted and re-drafted the polemical statements related to Anarchitecture, Matta-Clark wrote:

ANARCHITECTURE WORKING IN SEVERAL DIMENTIONS (sic) MAKING THE DISCUSSIONS THE SHOW AND THE WORK. KEEPING IT AN ONGOING PROCESS. NOT FINISHING JUST KEEPING GOING AND STARTING OVER AND OVER

Where Le Corbusier offered a mass-produced utopia, built on strictly functionalist foundations, Matta-Clark offered a model of what could be achieved both by individuals and at the level of the small collective, that through informal but intense discussion and shared experience could act as a hothouse for new ideas. Which, if we are still trying to pin down the word Anarchitecture, is probably as good a definition as we are going to get.

Fig.17

Gordon Matta-Clark

Creating Garbage Wall for Fire Boy at the Brooklyn Bridge 1971

Colour transparency

Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2007