This paper describes a programme I have led on behalf of Tate Britain over the last five years, and sets out some initial thoughts about the impact on it of a range of different, sometimes conflicting, influences and pressures. The programme is Nahnou-Together, which translates from the Arabic as ‘we together’ and, in this context, implies mutual learning. It is a partnership between Tate Britain, the British Council, the Adham Ismail Centre of Plastic Arts in Damascus and Darat-al-Funun, and the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Art in Amman, with support from the Jordan Ministry of Education.

Although Nahnou-Together was not envisaged as a research project, I want to view it as such, with the benefit of hindsight with which artists regularly describe the unexpected dimensions that shape an initial idea into a larger work of art or exhibition.1 I want to suggest that my management of the programme and production of a display at Tate Britain in 2008 was informed by, and in some ways mirrored, experience from my twenty-five-year career as an artist before I took the role of Head of Learning at Tate Britain in 2003. In this sense, as a manager in a museum, my development of the programme has frequently been as if I were an artist exploring the notion of ‘practice as research’ rather than the more conventional ‘project management’ introduced into the public sector over the equivalent twenty-five-year period as part of New Public Management (commonly known as ‘new managerialism’).2 However, I have viewed it as ‘practice as research’ only retrospectively, unlike the more commonly understood versions involving an artist articulating research questions to frame a fundable project. It may therefore be better described as ‘practice possibly leading to research’.

I hope to suggest questions that might lead to research questions, rather than to provide answers. I am writing as a subjective practitioner, unable to produce conclusions because of that identity, and because I sense the practice is extra-interdisciplinary, that is, not yet quite known. This paper aims to elucidate how some questions and issues have emerged or been provoked, how they have been addressed or left hanging.

In writing this paper, as well as in the course of the programme, I have recalled what I learnt in my early years of activist engagement with feminism as well as my work as an artist. Both these practices – the feminist and the artistic – have modelled and demanded reflexivity, and this has been endorsed through the practice of teaching and learning, a core subject in my current post. An aspect of this paper refers to my own learning through this programme that has, in part, made use of ideas I have absorbed over many years. For me theory is usually something that I assimilate but cannot necessarily identify through verbal language, though I know it informs my practice. The surprise for me in this programme has been that I was only able to use my assimilated theoretical knowledge once I have failed to use it in action: it helped me learn from my mistakes. Inspired by such artists as Francis Alÿs3 and theorists who have explored ideas of territory and boundary, I was introduced to an article by Alecia Youngblood Jackson which links feminist approaches to social science research. ‘The various deployments, critiques and reconfigurations of voice in feminist research,’ she writes, ‘are circular, inter-connected, and deterritorializing.’ She describes her text as ‘an assemblage and must be read as such’; and she refers to the writings of the French philosophers Deleuze and Guattari when she says ‘in this text there are “lines of articulation or segmentarity, strata and territories; but also lines of flight, movements of deterritorialization and destratification”.’4

In the context of Nahnou-Together such images of territory, strata, the breaking of boundaries, and flight are particularly resonant, not least because the programme involved repeated travelling by air between London, Damascus and Amman, and by road between Damascus and Amman. The Levant is an area of contested territories, clouded by Western media reporting of many cultures and countries as a single place, the Middle East; it is also an area of colonial mappings, as analysed and currently much criticised by academics, artists and others, unrestricted by location.5 Beyond this, it is a landscape renowned for the ancient material culture inspiring modern explorers, archaeologists, and artists, locally and from the West. To people who are unfamiliar with the region, the desert landscape appears endless and timeless, an imagined territory in which to let the mind play, whether with mirages or ‘whirling dervishes’. Certain local post-colonial artistic and political strategies reinforce ideas of cultural roots through reference to archaeological objects being unearthed from the desert,6 although these strategies are contested by many, particularly in centres for international rather than regional contemporary art such as Beirut.7

Youngblood Jackson’s theoretical model has helped me conceptualise my reflections on this programme. Here I am not treating theory as theory: I am merely glimpsing it, visualising images constructed to elucidate theory with those triggered by the sights I have seen from aeroplanes of the mountains rising in the fifty-three miles that lie between Damascus and Beirut, as well as from the discussions around art works with my Syrian and Jordanian colleagues, especially concerning modern Levantine art. In the course of this programme I have developed my own practice of ‘aeroplane thinking’ which I identify as a kind of musing between spaces, when I do not have access to books for facts or theories, but when I make reflective notes and develop ideas following intense activity and engagement with my Syrian and Jordanian colleagues. Aeroplane thinking is an activity of the ‘creative imagination’, with its inherent tightrope walk between fantastic projection (negative) and illuminating insight (positive).

Deterritorialisation and destratification are not simply found in feminist approaches or methodologies,8 but are often seen as important aspects of artistic identity and activity. Musician, writer and academic Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández has recently identified three concepts of ‘the artist’, which he has named the ‘cultural civiliser’, the ‘border crosser’, and the ‘representator’. The first is modelled on a liberal humanist tradition of civilising select groups and individuals. The border crosser is seen as interventionist, challenging and critical, as someone who takes an individualistic stance towards institutions. This type of artist is ‘perceived as having fluid identities and shifting roles in the construction of an imagined democratic public sphere’.9 Drawing on critiques of élitist definitions of culture, Gaztambide-Fernández analyses the ‘representator’ as one individual who among many contribute to the production and meaning of a work of art.10 In the context of a partnership between people and institutions from the UK and the Middle East, each of these three definitions can seem problematic because of the dominant political power relations. In addition, a single individual can assume any of the roles at different moments, a shift that can itself be seen or felt as transgressive or, more positively, destratifying.

Practice, participation, authority

Questions that have, for me, most pressingly emerged in the programme are how we, as artists and practitioners, experience our learning and how we come to know in practice what we know in theory; how a museum can genuinely be, as Tate describes itself, a place for sharing and participation; how individuals and institutions negotiate with each other in a critical relation to institutionalisation and power relations. These questions run between the lines of this paper.

Conventionally, museum curators identify with the ‘self’ of the artist, while gallery educators are situated as identifying with the ‘other’ of the visitor. Artists themselves frequently play with this construction, challenging their own authority as well as that of the museum and the visitor. In the work my colleagues and I are engaged in at Tate Britain, we regularly involve people – ‘visitors’ – to take on the role of artist or curator so that they, too, can play around, challenge and take authority. In this way we ‘deterritorialise’ and ‘destratify’, facilitating a composite meaning-making that springs from the idea of participatory cultural production.

At the centre of Tate, however, is the collection and its implicit authority-bearing status. Although Tate has recently acquired works by artists from the Levant, to date no acquisitions have been confirmed from modern or contemporary Syrian or Jordanian artists. On the other hand, higher proportions of the most important Syrian archaeological objects in public collections are likely to be in North America or Western Europe, a sensitive issue for a country that emerged from five hundred years of colonisation only fifty years ago. Further complications lie with Tate Britain’s engagement with national identity, migration and post-colonial culture, while issues of authority – who has the right to be shown, or to be seen, to criticise, to select, or to be collected? – inform a core part of Tate Britain’s work with young people.11 While the professionals involved in Nahnou-Together have possibly learnt more than the young people, it is work with young people that legitimised the programme.

Nahnou-Together

The Nahnou-Together programme has had several phases, which I define as:

- Phase One: February 2004 – July 2005

- Negotiations towards establishing a programme.

- Phase Two: August 2005 – May 2006

- The programme connects Adham Ismail Centre working with Syrian teenagers out of school with Quintin Kynaston School, London, working with GCSE students. Artists and educators exchange visits and teach students in both countries. Tate Britain works with the British Council Syria, creating a website and a display held at Tate Britain.

- Phase Three: September 2006 – September 2007

- Three new partners are recruited: the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Art, Darat-al-Funun (an art gallery and cultural centre in Amman), and the Jordan Ministry of Education. Adham Ismail Centre and Tate Britain change the direction of the British Council programme by initiating a mutual learning programme for all the professionals involved (approximately twenty-five). This results in a series of three three-day workshops over seven months, the production of a ‘tool-kit’, and a final workshop led by Reem Al-Khatib, Director of Adham Ismail Centre. The workshops were designed to develop knowledge of Tate’s pedagogically constructivist,12 informal learning techniques, and of Arab modern fine art. The workshop programme for the following year was agreed.

- Phase Four: September 2007 – September 2008

- A workshop programme with young people in Amman, Damascus and London, including a visit by the young people and professionals to each country. Research in each city is undertaken by the Tate contingent, resulting in filmed interviews with professional participants, as well as other artists and curators from Damascus and Amman. This film was included in the display Nahnou-Together Now in Tate Britain about what was learned from the programme.

- Phase Five: September 2008 – present

- Tate Britain develops a further programme, Illuminating Cultures, to develop knowledge of Levantine modern art for British teachers, school and college students. The programme involves producing resources, schools programmes, and post-graduate professional development for teachers. The programme will consult with Levantine artists, art historians and curators.

Contexts

The programme was initially developed with the British Council in 2004 at a time when the latter was beginning to implement structural changes. I was new in post at Tate Britain, and the Learning department was also going through structural change. Although I knew little about the Middle East, I was asked to investigate the possibility of a collaborative partnership with the British Council, and found myself becoming a central point for the programme in London, in partnership with Paul Doubleday, then Director of the British Council Syria, who involved members of his team.

On my first scoping visit to Damascus in February 2004 I met with artists, artist educators, artists’ representatives employed by the government, and dignitaries. The invasion that heralded the Second Iraq War was about to take place, but I found the Syrians I spoke to were far more concerned with what was happening in Israel/Palestine. Introduced as a Head of Education, I became aware that an American policy paper had recently been leaked which advocated promoting democracy in the Middle East through education programmes. I was conscious that my role was complex and open to question. I wanted therefore to develop a programme that was clearly of mutual benefit and exchange.

As well as the wider political situation, there were the internal politics of the institutions involved that influenced the programme’s development. To paraphrase Stephen Bach (Professor of Employment Relations at Kings College London), Britain has been in the vanguard of introducing New Public Management since the government has identified public service modernisation as pivotal in responding to the challenge of globalisation. Successive governments have introduced models from the private sector to improve public-sector efficiency, notably to improve the health and education of the workforce.13 In the education sector one manifestation is the National Curriculum, with its learning objectives and targets. Within an administrative context New Public Management takes the form of a model for project management which proposes aims, objectives and an evaluative framework, whose emblem is the Gantt chart. As a methodology, it impacts on how one thinks or proceeds and, by extension, what one chooses to proceed with or, at least, how one measures one’s options.14 It is a still contested approach but for younger generations has been completely normalised.

Learning to go beyond process

From Tate Britain’s point of view I considered the initial phase in London a failure. Disproportionate attention was paid to the ‘other’ countries and the internal workings of the lead partner organisations, while the complex workings of the London school were relatively neglected. While the Adham Ismail Centre embraced the programme and the students there became immersed in a continuing dialogic project, the London students’ experience was dominated by the school’s existing schemes of work to support the GCSE syllabus; their engagement with the programme and with their Syrian counterparts was relatively superficial. As the project started to take shape, it gradually became clear to me that, as well as Arabic and English, there were different and sometimes conflicting registers of English being spoken: a pragmatic language in which a spade was called a spade, and an institutional language that, for instance, called an art work an output. The Syrian partner, the Adham Ismail Centre, was represented by practising artist educators, who had been isolated from the conventions of New Public Management, but whose sense of themselves as artists might be described as ‘civiliser’ and ‘border crosser’, to use Gaztambide-Fernández’s terms . In this context I frequently found myself intellectually and emotionally identifying with my Syrian colleagues who privileged originality, individuality, spontaneity and imagination over organisation and team work.

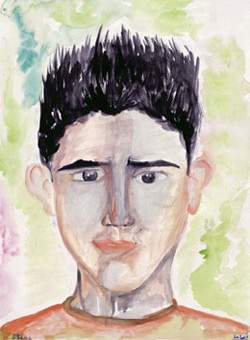

Fig.1

Adham Ismail Centre

Photograph © Felicity Allen

On my scoping visit to Damascus, hosted by the British Council in February 2004, I met Reem Al-Khatib, artist and Director of the Adham Ismail Centre (a small art college for children and adults that is not part of a public examination system but that has an informal relationship with the Fine Arts Department at the University of Damascus). I mentioned the idea of developing an international project with young people (an imperative of the British Council) using animation and calligraphy. (I later saw some beautiful film works by Kutlug Ataman that did just this.)

Reem’s response was straightforward. Animation is not art (which is painting, sculpture and printmaking), and the Syrians had had enough of the West’s stereotyping calligraphic fixation. She wanted us to recognise Syrian traditions of rolled- and fixed-stamp printing rather than the more generic Arabic calligraphy. Initially, Reem and her team frequently expressed the idea that young people should not be exposed to the work of professional artists because it might influence them; they needed to work fresh from their imagination. (It was a view that I remember as prevalent in my primary school education in the late 1950s and 1960s, but for my younger British colleagues this idea was entirely novel.) However, once the programme of work had started, the artist educators from Adham Ismail Centre visited Tate Britain and, for the first time, became aware not only of the scale and wealth of the institution they were partnering but also of the different ways in which Tate Britain engaged with its many visitors. This appeared to shift the artist educators’ view: they recognised that building knowledge of Syrian and Arab art was strategically important in developing wider social and political support and interest in art.

In 2004 the only large public museum in Damascus, now known as The Damascus Museum, displayed antiquities to a public who mostly did not come. Upstairs, behind locked doors, it stacked or ‘displayed’ modern Arabic paintings and sculpture that formed part of the Government’s Art Collection. Conservation was non-existent and information, including artist’s name, title and date of the art works, was not available. Viewing was by appointment only.

Fig.2

A work by Naseer Chaura in Damascus Museum 2006

Photograph © Felicity Allen

The question of how to share knowledge, I realised, was critical. How to deal with the power accumulated by knowledge in this partnership of a country little known to the West with the culturally dominant United Kingdom? After a period of activity with the young people in both countries, I visited Damascus alone in February 2006 for the launch of an exhibition Reem had organised of the Syrian young people’s work in the remarkable Khan As’ad Pasha building in the Souk. I gave a lecture to a general audience about the work of the Tate Britain Learning department, and while there was invited to improve the exhibition’s captions as my Syrian colleagues lacked experience in this area.

During this visit I met five members of the Adham Ismail Centre professional team, all artist educators, and Laila Hourani, the Syrian project manager from British Council Syria. The meeting was seminal and led Reem and me to dismantle the existing project plan and reframe it in a way that allowed the partners to explore unknown territory together. The meeting set out to evaluate what we had achieved to date, but we quickly moved on to enjoying an animated and sometimes difficult discussion about attitudes to, and knowledge of, modern and contemporary art. At this point I began to realise for the first time that I could not think of Syria as simply lagging behind Britain in its artistic development. I had been falsely comforted by what had felt enjoyably old-fashioned attitudes to art, a misinterpretation based on a progressive model of history. I started to see that, for some but not all of these artists, Islamic attitudes towards art’s purpose were influencing how they practised, though they were not making traditional Islamic art but what the West calls fine art.

My understanding of the purpose and practice of art are inevitably Western and interpreted through years of my own practice, as well as reference to other European and American artists. The programme, and especially the February meeting in Damascus, has led me to reflect more deeply on how artists from the East and West describe their practices and their learning. Although this is not central to the main subject of this paper, I should like to cite here the words of Richard Serra and Carl Andre, two artists whose sculpture relates strongly to the land, and whose descriptions of their practice resonated with my own experience of working through the development of this programme. ‘I never begin to construct with a specific intention’, Richard Serra has said. ‘I don’t work from a priori ideas and theoretical propositions. The structures are the result of experimentation and invention. In every search there is always a degree of unforeseeability, a sort of troubling feeling, a wonder after the work is complete, after the conclusion. The part of the work which surprises me invariably leads to new works. Call it a glimpse; often this glimpse occurs because of an obscurity which arises from a precise resolution.’15 Similarly, Carl Andre once wrote, ‘It is exactly these impingements upon our sense of touch and so forth that I’m interested in. The sense of one’s own being in the world confirmed by the existence of things and others in the world.’16

The surprise of the discussion in February 2006 – and my desire to know and understand more– seemed to me to contribute to motivating Reem and her colleagues to change their aspirations for the programme. Reem told me she wanted the British partners to recognise, rather than merely glimpse, the fine art that Syrian artists had been producing for the last century with their own modernist discourses. At the same time, she wanted to learn our techniques for engaging young people in looking at art. The British participants, however, were less clear about the knowledge exchange.

When interviewed about the project, the Head of Art at Quintin Kynaston School, said:

I got on board quite late. Quite a lot of the children in my school are Muslim. For me it was about finding out about the country and art in that country … I didn’t see myself as passing on anything I knew. It was about me finding out from them. I didn’t see myself as someone who had to pass on some great knowledge because I don’t see myself like that anyway.17

Here the British teacher negates her own knowledge and power and, in doing so, appears to be withholding, not giving. I interpret this as a complex attempt at refraining from taking a colonial attitude while not having the critical or reflexive system in place to consider the politics of such a position.

With hindsight, I have come to think about the different cultural influences present in the British team: the teacher was from a British Caribbean background, the artist was from a British Asian Muslim background, and a range of Eastern and Western European countries were represented in the group. However, we did not attend to what our cultural mix might mean for us at the time, how it felt to have a mix of British identities in Damascus, responding only to a desire to present a glimpse of the inter-cultural reality of London life to the Syrians. A key objective of the British Council was that everyone in the programme should gain a more nuanced understanding of the two countries involved, but the lack of familiarity with each other’s expectations led to difficult, though often stimulating, explorations on the fault lines of misconceptions. Working through these, a deeper commitment and understanding of each other shaped the programme in personal as well as professional ways, transforming it from a managerial model into something uncharted and dynamic.

Ahmad, a twelve-year-old Nahnou-Together participant at Adham Ismail Centre, echoed the sense of the uncharted, and in the context of this paper echoes the thoughts of Carl Andre quoted above, when he wrote in 2005–6, ‘When I draw I feel part of the world’. For a Syrian child whose country has been isolated and vilified in some quarters, this has an additional intensity. He reveals the imaginative concentration of power he gains through drawing, which in turn forms a kind of mapping of self.

Despite or perhaps because of the several failures of Phase Two, we continued the programme, expanding it to involve participants from Jordan as well as Syria. The British Council still wanted us to develop programmes with young people immediately – the imperative to be seen to work with young people was very strong – but Reem and I offered a new plan for the programme which resulted in twenty-five educators, artists, curators and British Council staff holding four workshops of three days each between December 2006 and September 2007. I facilitated the first three, Reem the last one.

Fig.3

Workshop in the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Art, February 2006

© Courtesy Jordan National Gallery of Fine Art

During this period Anwar Abbas joined the group, representing the British Council. Eighteen months later he emailed me: ‘I don’t think that in the past 300 years we have lacked people or institutions that are interested in the East politically, culturally or artistically. What has been lacking so far and will continue … in the foreseeable future are individuals and institutions who, to paraphrase Edward Said, can go beyond the first impressions into actual encounters.’ Going into Phase Three the group of professionals aimed to go beyond first impressions. By continuing and building on Nahnou-Together, without a long-term project plan or backer, Tate Britain was challenging conventional arrangements for gallery education programmes: it was styling this programme as long-term, in-depth and exploratory, in contrast to the default short-term tokenism that typically besets gallery education programmes when funding runs out. In this sense, it was perhaps more like a curatorial or artistic project. While objectives around learning exchange and young people were in place, the methods were based on the practices – discursive, argumentative, practical, open-ended and playful – that the core members of the group brought with their artist-educator professional identities.

Emotion and warmth as materials

More than half of the professionals engaged in the Nahnou programme, from Damascus, Amman and London, had a background in art practice. As well as developing practical games and techniques to develop observational skills, I asked each of my colleagues to develop a presentation about an Arab artist and to engage the workshop in discussion in Phase Four. I contributed a session on the work of the Syrian artist Mahmoud Hammad whose work had become increasingly interesting to me since my first visit. As a model for mutual learning it therefore included several important factors: I had found an artist whose work interested me; I had gone on to try to find images and information despite a paucity of published material in English, scholarly or otherwise; my colleagues were able to give me further information or correct my misconceptions in the workshop; and they told me they experienced this discussion around particular works of art as a good model for learning. They also told me that it helped them to look again and more deeply into the work of Mahmoud Hammad. For me looking again – going beyond the glimpse – was an important accolade.

I had already observed how we were using warmth and humorous dissent as a continuum underpinning our meetings. Together we kept ‘learning logs’, reflecting on our learning, bringing to bear our different experiences, and developing knowledge and trust. When we explored informal learning techniques together, some valued having fun and being spontaneous, and cited having warm feelings towards a teacher as key to good learning. I had been told by a Jordanian participant who had been educated privately and a Syrian participant who had been educated in the state sector in their respective countries, that state schools in both Jordan and Syria used teaching models based on what the educationalist Paulo Freire terms the ‘banking’ model from which fun, sensuality and imagination were eliminated in favour of drilling knowledge into learners.18 Art is not taught as a subject, and school students are scored each year in order to identify professional aspiration: engineering and medicine are at the top, while art is only one above sport, the lowest on the table.

Dialogue was intense – and frequently challenging – in the workshops, which shifted between warm, funny, cool and angry. Two young women – an artist and an art historian, curators from the Jordanian team – chose to prepare together a complex presentation to discuss the work of the young Egyptian artist Amal Kenawy, whose work challenges Arab conventions around the display of female sexuality and the body. The group was polite in its discussions, even though most of the men in the group individually and differently criticised the quality of the artist’s execution of her work; the women were mostly quiet and one man said he liked the work. The curators had put considerable work into their preparations, selecting together the work they wanted to present, discussing it together and, in planning the workshop, followed guidelines they had read in a Tate-produced educational publication I had given the gallery.19 They combined a discussion of a potentially challenging artist with a high desire to produce a good workshop which was more open and questioning than a conventional public presentation in the gallery might be. However, they appeared to anticipate hostile reactions to the work, and scattered a number of questions to the group:

A: If she organised her ideas better would it be better? Do think a clear scenario is better? For example, a story?

B: …An artwork should have components. The way it was linking between scenes was not a good one …

H: You can’t say she shouldn’t have done that – it’s her prerogative.

B: I think she could do better.

After an extended discussion – longer than planned – I suggested that we call a halt and find time to pick it up when we had an appropriate amount of time the following day. I asked all the participants to make sure they spent at least half an hour looking at Amal Kenawy’s time-based exhibition on display in the gallery before they returned for the follow-up workshop. I asked the presenters to think through how they presented and after the second presentation gave them feedback. At this stage it transpired that the presenters themselves were uncertain about the work but, because it was on display in the gallery where they worked, they felt a professional imperative to discuss it with the group. Coming back and giving proper time both to the exhibition and the workshop enabled a shift to take place: people who spoke tended to give more complex responses, including the two presenters.

In this phase, the group of artists, curators and educators who met together took on all three of Gaztambide-Fernández’s artists’ roles: civiliser, border crosser, and representator, although the product was entirely process.

Exchange

The fourth phase, from August 2007 to March 2008, involved groups of young people in Amman, Damascus and London, working with artists and educators, to explore contemporary art and visual culture in either their own country or the others, or both. Each group identified its own priorities. In London the group of twenty young people, aged between fifteen and twenty-one, came from six schools and four colleges to work with Tate staff and artists, including Maria Zeb Benjamin, Faisal Abdu’Allah and Indie Choudhury. The programme intentionally brought together young people from very different backgrounds. Participants’ comments from a comparable programme, Visual Dialogues, revealed that they have enjoyed being released from the intense social stratification that marks teenage culture, suggesting that Tate offered them a place where they could discuss sensitive political issues in a safe environment.

Teachers from the schools were invited to participate in a programme to investigate Syrian and Jordanian art and culture, and to consider how this knowledge could be incorporated into their teaching; three out of eight stuck with it.20 Lucetta Johnson, a doctoral student from the Courtauld Institute of Art, helped me to build up knowledge of the development of Syrian and Jordanian fine art and its cultural and educational infrastructures.

There followed exchange visits by young people, artists, curators, educators and British Council staff, to each of the three countries by each country group. In February fifteen members of the British group made a ten-day visit to Jordan and Syria, collaborating in practical workshops with their counterparts there, visiting art galleries, museums and the ancient sites of Petra and Palmyra. Building on the desire to create more knowledge of art, artists and art infrastructures in Jordan and Syria, I worked with filmmaker Trevor Mathison to interview some of the professional participants as well as other artists, curators and art historians. These films were edited for display in summer 2008 at Tate Britain.

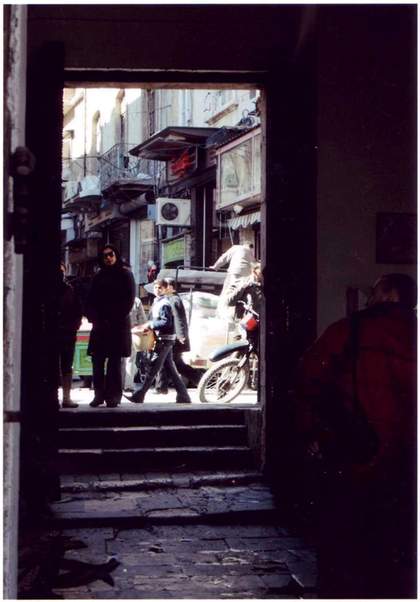

Fig.4

Damascus 2008

Photograph © Sonia Yekini

On their return to Britain, students worked with Faisal to develop screenprints at London Printworks Trust, from their drawings, notes, writing, and photographs; one student, James, chose to develop a poem alone and withdrew from the programme to devote himself to his impending A levels. Each student contributed in some way to the display, Nahnou-Together Now that was held at Tate Britain in 2008. It was timed to complement and run concurrently with the exhibition of British Orientalist painting, The Lure of the East – with its complex, multi-vocal interpretation representing East, West and diasporic views – and the solo artist show Mitra Tabrizian. The display aimed to reflect experience and knowledge gained by the British contingent through the previous eighteen months of the programme. It was held in the Goodison Room, off Tate Britain’s central Duveen Galleries, was advertised on the Tate website, and was accompanied by a free guide which included images produced by students and artists. It included a large photographic wall piece produced by Faisal Abdu’Allah from his own photographs with images created by some of the young people he had worked with; a mind-map/timeline situating the development of the three partner institutions in the activity of modern Syrian and Jordanian individual artists and educators; filmed interviews with Syrian and Jordanian artists and curators, including some who had participated in the programme; selected folders of work produced by British, Syrian and Jordanian young people; and a film exploring the exchange workshops made by Trevor Mathison.

On the walls beside this film were captured some of the comments made by students after their return from the programme visit. They included:

Lorenzo: ‘I’ve always been, like, I didn’t believe everything the media said, but now I can say it’s wrong because I’ve been there.’

Claire: ‘I realised that Jordan and Syria were really different from each other, and there were so many differences in their difference.’

Anita: ‘I was disappointed by the desert – I expected it to be more sandy.’

Ben: ‘When I saw a Burger King I was really disappointed but as soon as I got back I had one.’

Lorenzo: ‘I can’t forget the Bedouins.’

Stan: ‘It’s important not to say “them”, not the “Middle East” otherwise you’re taking away everything we learnt.’

Sonia: ‘I see them as just the same as us. Jordan is much more influenced by the West.’

Comments that the Syrian young people had written in the UK students’ sketchbooks included:

‘Don’t explain your work because it could ruin someone’s own interpretation.’

‘Only give a general theme.’

‘If people don’t get what you wanted to get across, it’s the artist’s failure.’

and

I love the beat.’

Despite differences in age and culture, the young people from each country had shown every sign of enjoying getting to know more about one another. The Londoners had been disarmed by the warmth of their counterparts, and found relief in letting go of their own cultural ‘cool’. James wrote:

Never before had we come across people who wanted to both share so much and find out all they could about us British students; it was an exchange that worked on so many different levels. The last afternoon … after a day of creating collaborated artwork with our Syrian friends, they decided to show us a traditional dancing game, and free of any inhibitions or cultural barriers we all took part dancing and exhausting our chests laughing while a Syrian boy, Tomi, provided rhythm on his drum.21

The spontaneous dance generated by the young people in fact displaced the evaluation session that had been programmed by the British Council – the dance was the evaluation.

Display

Tate Britain has held two displays about Nahnou-Together, first in 2006 and more ambitiously in 2008. They were curated only by the British because the programme had not positioned itself as an international curatorial programme with appropriate levels of resource.22 The two displays were the subject of entirely negative criticism by some individuals in the partnership, even though the second took on board initial responses to the first. The authority of Tate to represent the programme was problematic, and possibly exacerbated by the fact that Tate had not yet acquired work by artists from either Syria or Jordan. The disparities in experience, knowledge and values in relation to curatorial production exacerbated the tensions, while a technical fault resulting in temporary failure to display subtitles in the films was interpreted as a silencing.

Fig.5

Timeline-mindmap, Nahnou-Together Now 2008

© Tate

A sense of mis- or under-representation applied also to the British group of young people, some of whom felt their work was given insufficient prominence. On the other hand, Lucetta Johnson’s Courtauld student colleagues, until that point unknown to her, approached her with unsolicited comments endorsing the 2008 display:

‘I had no idea there was so much art in Jordan and Syria.’

‘I never thought about there being art movements in Jordan and Syria.’

‘I didn’t think I’d see an exhibition on contemporary Jordanian and Syrian art at the Tate.’

‘It was really dynamic. It was great to see the artists talking about their work.’

Sensitivities around representation and the pleasures of new knowledge are the stuff of curatorial and educational work. Together they demonstrate the tension between the museum’s aim to be a place for sharing and participation, and the museum’s authority. Nahnou-Together was conceived initially as a short-term project in which young people would be guided in activities by professional institutions with highly politicised and complex motives. In this context the young people were safely amateur. The programme progressed to a position in which the professionals acknowledged their need to know each other and each other’s cultures and motivations, and integrated their own learning into the learning programme as a whole. The professionals acknowledged their role as participants. This process opened up the possibility of individual critique of the institutions that represented, and were represented by, the participants. However most of us feared the consequences of becoming ‘unprofessional’, and to a lesser or greater extent were conscious of different imagined or actual forms of professional reprobation. The borders being crossed included the concepts of amateur and professional, an integral part of the authority of institutions.

Theory, past and present

Tate Britain is developing a new programme out of Nahnou-Together, to share and build understanding on the knowledge gained. It is now confronting the intractable issues about how to gain and share knowledge about the modern cultures of the Levant at a popular level with Londoners. How to explore knowledge about a culture that the people who live it have not yet described or ordered in forms that are accessible or intelligible to people based in Britain. How to learn from the considerable work on ideas of truth, memory, archive and history produced by artists and theorists in Beirut while recognising the distinctions between that work and the developments of closely neighbouring urban centres representing Palestinian and Syrian cultures, which are themselves distinct from each other.

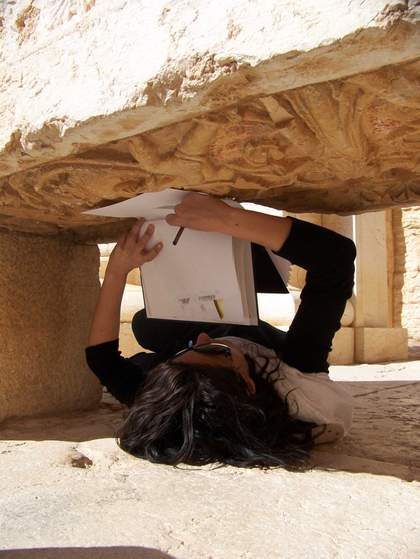

Fig.6

Student exchange 2008: drawing at Palmyra

Photograph © Trevor Mathison

I have learnt from Nahnou-Together that one must focus on process rather than narrowly defined targets, and the process should refer to the knowledge gained about being prepared to fumble in the dark, to doubt and not to know, as well as to keep listening to theory and looking at practice to help reflection. This includes self-reflection. Although I have been engaged in debates about feminism, museums and colonialism all my life, I felt in this project that I had to learn again in a completely different way: the learning now feels embodied, in the body of me as I am now, not as I was ten, twenty, or thirty years ago. I have looked again at something that I heard cultural theorist Stuart Hall say years ago and realised it describes where I am now in the museum through Nahnou-Together:

Museums have to understand their collections and their practices as what I can only call ‘temporary stabilisations’. What they are – and they must be specific things or they have no interest – is as much defined by what they are not. Their identities are determined by their constitutive outside; they are defined by what they lack and by their other. The relation to the other no longer operates as a dialogue of paternalistic apologetic disposition. It has to be aware that it is a narrative, a selection, whose purpose is not just to disturb the viewer but to itself be disturbed by what it cannot be, by its necessary exclusions. It must make its own disturbance evident so that the viewer is not entrapped into the universalised logic of thinking whereby because something has been there for a long period of time and is well funded, it must be ‘true’ and of value in some aesthetic sense. Its purpose is to destabilise its own stabilities. Of course, it has to risk saying, ’This is what I think is worth seeing and preserving’, but it has to turn its criteria of selectivity inside out so that the viewer becomes aware of both the frame and what is framed.23