1. Introduction

This report presents the results of audience research that sought to explore the following question: how can Tate identify, understand and articulate the different ways in which it creates value for its audiences through its ticketed exhibitions programme? The first part of this report describes how the project was undertaken and the methodologies used, then considers Tate’s basic models for exhibition planning, including how small and medium enterprises or SMEs (such as micro-businesses and freelance artists and curators) contribute to these processes, and looks at how the gallery currently collects information about its exhibition audiences. The second half of the report presents the findings of the exhibition case studies that were undertaken in 2014 and offers some interim conclusions for reflection and discussion.

In addition to the major question set out above, the additional, contributory research questions that this project sought to address were:

- What type of values does Tate create for its audiences through their attendance at a paid exhibition? This includes what they learn and take away with them, and what their experience is of viewing the exhibition (the ‘exhibit face’).

- How do the different people who make up that audience experience exhibitions?

- Do visitors want to hold on to that experience, and if so, how can Tate accommodate that need?

- What is the level of satisfaction amongst audiences? Can it be measured with any accuracy?

- How does Tate’s habitual collaboration with creative SMEs contribute to the visitor experience?

The research project was undertaken in the summer and autumn of 2014 by Mariza Dima, working under the auspices of the audience research strand of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Knowledge Exchange Hub, Creativeworks London. It was carried out in collaboration with Tate Research and with significant input from the learning and curatorial teams at Tate Britain and Tate Modern. The focus of the work was Tate’s visitors and in particular the audiences for two major ticketed exhibitions that were presented during the project period: Malevich at Tate Modern (16 July–26 October 2014) and Late Turner: Painting Set Free at Tate Britain (10 September 2014–25 January 2015). These two exhibitions were chosen because they allowed comparison between Tate’s two London sites, their audiences, organisation and methods of exhibition planning and delivery.

The aim was to capture the emotional-affective responses of visitors to the exhibitions and to evaluate the learning outcomes of the experience. In addition, we were interested in how the audience response to exhibitions reflected curatorial imperatives, as well as its possible impact on curatorial decisions, interdepartmental working at Tate, and collaborations with external SMEs.

2. Tate’s practice of evaluating exhibitions

Across the four galleries – Tate Modern, Tate Britain, Tate Liverpool and Tate St Ives – around a dozen ticketed exhibitions are presented every calendar year. A series of interviews with key people from all Tate departments, both on-site and cross-site, and from all four Tate gallery sites, helped the researchers to understand Tate’s current practices with respect to its exhibition audiences. Reflecting on past evaluations also exposed significant differences in the ways that each site collaborated with external creative SMEs – if they collaborated at all.

Little evidence was found of in-depth qualitative evaluations of the audience journey or experience in relation to the audiences for paid exhibitions at all the Tate sites. The evaluations undertaken at the time took three forms: general audience surveys which were carried out by the Visitor Experience department; research by external companies commissioned by the Audiences department; and benchmarking against visitor data from other national museums and galleries, which was also undertaken on Tate’s behalf by external companies. The visitor experience survey was focused on collecting demographic information about the visitors and assembling data relating to frequency of visit, motivation for visiting, and levels of satisfaction measured according to the Lickert Scale method.1 The research commissioned by the Audience Research team collected qualitative data and analysed in line with a segmentation-based audience model and an experience-based model.

At the time of writing this report there had not been systematic in-depth analysis undertaken on behalf of Tate concerning those who pay to see a ticketed exhibition. However, an evaluation was undertaken by Morris Hargreaves McIntyre (MHM) of the free exhibition and festival The Tanks: Art in Action, held at Tate Modern in 2012, which considered the make-up of the audience for that exhibition, their experience and the outcomes for Tate. This work was commissioned because the exhibition, which comprised live art shown in a new gallery space, was an experimental innovation for Tate. The MHM report makes it clear that the methods employed included standard ‘heavy’ questionnaires and a financially incentivised online survey as well as exit interviews with audience members.

By contrast, Tate’s cross-site Learning department has a strong record of conducting evaluation targeted at understanding how participants engage with its teams’ work, seeking to discover what is actually being learned and using the insights to design the future programme. To achieve these results, the Learning department uses a mixture of quantitative and qualitative analysis through questionnaires, interviews and participant observation (for which they hire external evaluators). An example of a project that included action research and a values-based evaluation framework was the ‘Transforming Tate Learning!’ project that was carried out in 2011–13 with the support of the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. A second evaluation of an aspect of the learning programme, this time focusing on young people, was the Circuit project evaluation framework, completed in 2014.2

Tate’s Audience Research and Digital teams monitor audience analytics for on-site and online visitors for all exhibiting activity (both the ticketed exhibitions and the non-ticketed displays of the permanent collection). To support their analyses they have used the aforementioned segmentation model that divides Tate’s audience into nine different clusters. The data that can be set against this model is particularly useful for understanding the constitution of Tate’s audience, the fluctuations that occur within and between the different segments at specific periods of time (usually by month and year), and what this means for the particular gallery site and for the art museum overall.

However, despite the relatively high levels of understanding about the different social types and individual characters that make up Tate’s audience, little evidence was found to suggest that the knowledge that is gained through this audience research is synthesised in order to inform Tate’s exhibition-planning process. This information is used extensively on a marketing level but not during the creative, curatorial process.

Discussions with curators revealed that the content and programme for the ticketed exhibitions is led by an idea that originates within the curatorial team. In arriving at these ideas, curators try to accommodate a range of different audience types and perspectives around an exhibition theme, but the nine identified audience clusters and the personae that are built for each exhibition are not considered within the curatorial process. Instead, these tools are used by the Audience Research, Marketing and Development teams after they have been briefed by the curators in order to draw up values for the potential types of audience and to plan an appropriate marketing campaign.

In addition, there was not much evidence at the point to suggest that Tate had pursued research regarding the audience’s motivations, aspirations and expectations for visiting a specific exhibition, such as those that this research project has experimented with and that have the potential to be valuable to the curators during the exhibition planning process. Instead of creating an exhibition based on an understanding of the audience base, the various Tate departments – Marketing, Digital, Media and others – had been asked to contribute ideas and to find relevant collaborations for making an engaging programme based on audience types and demographics that are speculative – the audience that is thought likely to visit the specific exhibition.

Furthermore, in relation to audience participation on more advanced levels such as co-creation and co-curation of exhibitions, there is no record that there has ever been an audience-curated exhibition at Tate, even at an experimental, small-scale level, apart from some online engagement projects initiated by the Digital team. An internal report on one such initiative – the digital mass participatory project entitled ‘The 1840s GIF Party’ – shows that it invited audience participation rather than co-curation, and was not directed at any major paid exhibition but instead at one of the occasional Late at Tate events.3

It may be significant that Tate appears to take an approach to audience research for ticketed exhibitions that is similar to the way that information was structured on its website, which at the time of this project displayed a fragmented picture of each department’s work but which also served a number of specialist audiences. Our understanding is that the strategy of the Digital department is that it will move over time to a more audience-oriented organisation of information on the website and will add more content directed at the general public.

The remainder of this report will outline the research methodology used for the project, then attempt to synthesise the findings from the data produced by our research project and set out a range of topics for further consideration by the museum.

3. Research methodology

The information that was collected about the audiences for Tate’s ticketed exhibitions took the form of responses from visitors regarding their experience of that show through all the stages of their journey: from the point of entry, at the ‘exhibit face’, and through to the exit. The goal was to understand whether or not they were immersed in the overall experience, if there were moments when their ‘smooth’ journey was broken and the reasons for this, what was learnt as a result of their visit and what else affected them during their time in the exhibition. In order to collect such information – much of which was tacit – we designed a method that would motivate those questioned to participate willingly, that would not be too intrusive in relation to their visit and that would allow them time for reflection.

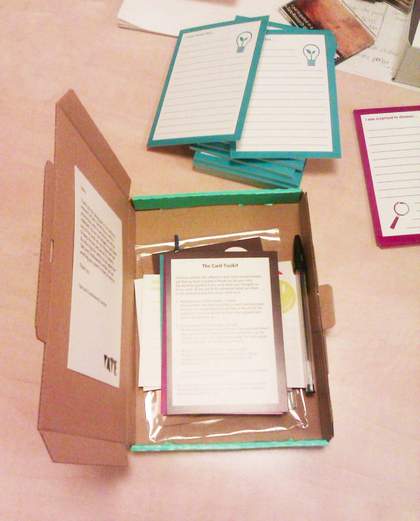

Fig.1

The box of cards and its contents

Photo © Mariza Dima

We decided to use cards with ‘reflection-probing’ sentences written on them that intended to elicit thoughtful responses about the learning process and emotional feedback, as well as providing a chance to reflect on the card method itself. The cards were placed in a small lightweight box, which also included a consent form, a pen for filling in the answers and a thank you gift (fig.1). The cards were created with the help of Tate’s Design Studio, adhering to Tate’s visual guidelines, and they were printed in playful colours to appear visually appealing.

The sets of cards took the following form:

- An introductory card that gave instructions about the assignment.

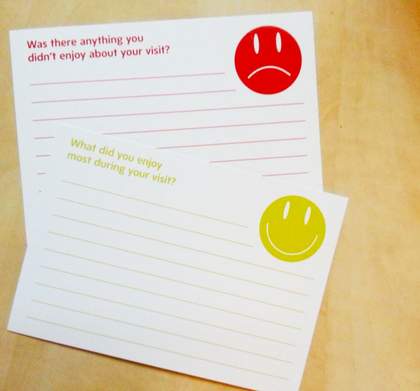

- Two cards about ‘enjoyment’: one green card with a text that read ‘What did you enjoy most during your visit?’ and one red card with a text reading ‘Was there anything you didn’t enjoy about your visit?’ (fig.2)

- Two cards about ‘learning’: one purple card asking the reader to complete the sentence ‘I was surprised to discover…’, and one blue card asking the reader to complete the sentence ‘I never knew that…’

- A card that prompted self-reflection, asking: ‘Did answering our questions affect your experience of visiting the exhibition and, if so, how?’.

The thank you gift took the form of a custom-made fridge magnet showing images from the Malevich and Late Turner exhibitions respectively. A thank you note, signed by Tate’s then Head of Research, accompanied the pack.

The consent card, which participants were asked to return at the end, read as follows:

Hello. Thank you for taking part in our audience research at Tate. Everything you write is anonymous and no personal data will be collected. You are not obliged to give in any of the cards you use. Please feel free to keep anything from this box.

By returning these cards you agree that Tate and Creativeworks London can use anything you submit to them for analysis.

Fig.2

The ‘enjoyed’ and ‘didn’t enjoy’ cards

Photo © Mariza Dima

The research method did not include the collecting of demographic information or other data from the participants, since this was considered independent from the affective values we sought to record. Knowledge of the demographics of the specific audience might have been relevant for different research purposes but it was outside the scope of the project.

Research staff were positioned with the boxes of cards next to the box office at Tate Britain and Tate Modern and approached visitors as they were coming to buy or collect tickets for the exhibitions. At Tate Britain we were able to approach Tate members directly, since they enter the exhibition without having to purchase a ticket and the box office is situated close to the exhibition entrance. Unfortunately, we could not do this at Tate Modern since the box office is located two levels down from the exhibition entrance.

Our procedure was as follows: we approached people who were waiting in the ticket queue, briefly explained the project to them while showing them the opened box, and asked them if they would be willing to participate. Most agreed immediately, while some wanted to read the cards first in order to check the amount of time it would take to fill them in and a few declined politely due to lack of time. When a visitor agreed to take part, we explained in detail that they should read the cards before entering the exhibition and reflect on them during their visit, and that they were free to write on the cards during or after. We also showed them the gift near to the end of the explanation, deliberately not mentioning it at the beginning as we did not want it to form the sole incentive for their participation. Children and families were excluded from the sample since the completion of the cards required a level of concentration that may not have been compatible with supervising children. At the exit of the exhibitions the cards that had been completed and collected were pinned up for other participants and visitors to see. A total of ninety-eight boxes were given out, forty-nine to visitors of Malevich at Tate Modern and forty-nine to visitors of Late Turner at Tate Britain. Of these, thirty-six were returned at Tate Modern and forty at Tate Britain. In addition, some participants were eager to engage in conversation when they were returning their cards and their comments have been integrated into our analysis where applicable.

4. Analysing the collected data

The analysis that follows considers primarily the cultural and social values derived from Tate’s exhibitions by its multicultural audience. We analyse the data in two parts (4.1 and 4.2). The first is an overview, which highlights usability issues, identifies general patterns in each site’s audience and juxtaposes discernible differences between the two sites. In the second part we focus on the learning aspect of the audience visit for the two exhibitions respectively.

4.1. Patterns, issues and opportunities

The sample of Tate Britain’s audience that was analysed for Late Turner was, in general, very knowledgeable about the artist, and all of the participants visited the exhibition because they knew something of Turner’s work. They all stated that the thing they enjoyed most during their visit were the paintings and the fact that the exhibition enriched their knowledge about Turner. Some further comments from the audience response cards included:

‘For me, the entire exhibition threw light on Turner’s work. I’d seen Tate’s permanent collection, and this Late Turner exhibition extended my knowledge.’

‘The number of works, the variety and interpretation. A great insight into a wonderful painter. The sketch books were a joy.’

‘It is very emotional to see Turner’s late work.’

By contrast, only 44% of the audience for Tate Modern’s exhibition on Malevich visited because they knew Malevich’s work, while 12% had little knowledge of Malevich and the remaining 44% had not heard of the artist. What explains these markedly different findings? They might be related to the fact that Turner is better known than Malevich at least for the British audience, which, according to the box office, made up the majority of visitors to Tate Britain (66%, as measured between October and December 2014). Equally, Late Turner was an exhibition about a specific period of the artist’s work, so it could be that the majority of the audience would have had to be at least slightly knowledgeable about the artist in order to pay to see such an exhibition. However, the differing findings might also correspond to Tate Modern’s status as a popular venue with tourists and younger people, as well as art audiences. Research undertaken elsewhere has confirmed that Tate Modern is considered to be a landmark venue for London and a ‘must-see’ place to visit for tourists and art aficionados.4 There is also strong trust in the Tate Modern brand and strong emotional equity (as evidenced by the internal report following the initial season of the Tanks performances). Each of these factors may lead some of its audience to visit any exhibition that is presented at Tate Modern irrespective of the artist whose work is shown.

4.1.1. Content of interpretation

Visitors to both exhibitions commented on the overall curatorial approach that had been followed, registering their opinions through the ‘enjoyed’ and ‘didn’t enjoy’ cards. One striking difference between the two audiences was that Tate Britain’s audience challenged the curatorial narrative in ways that Tate Modern’s did not, except for a few comments on the way the works were hung in relation to the design of the exhibition (a finding that will be addressed below in section 4.1.2).

The following comments about the two exhibitions reveal this contrast. Statements on the Late Turner audience response cards included:

‘Duplication of subjects.’

‘I was confused as to how the etchings fit into the story of Late Turner.’

‘Uncertain whether Turner would have wished unfinished and private work to be on ‘display.’

While the following comments were made about Malevich:

‘I enjoyed seeing how Malevich evolved as an artist. It was interesting to see his different personal movements displayed so well throughout the exhibition.’

‘The information on the influences Malevich was exposed to – the way his works stand in a historical and critical context.’

It is possible that these comments reflect the fact that the Tate Modern audience had little or no knowledge of Malevich’s work.

The praise among the Tate Modern audience for the chronological arrangement of the Malevich show suggests that it is important that exhibitions offer a clear historical outline of an artist’s work, particularly for the benefit of a less knowledgeable audience. Achim Borchardt-Hume, curator of the Malevich exhibition, has commented: ‘People appeared to like the story-telling aspect, which confirms that exhibitions are read in time and space and that it is important to use a clearly articulated story, as a thread that can be read’.5

On the critical side, a few fairly knowledgeable participants disagreed with the curatorial interpretation in the Malevich show. These comments are taken from different ‘didn’t enjoy’ cards:

‘Numerous captions were annoying, stating the obvious and in a tone of superiority.’

‘Perhaps less basic signage for those that already know about Malevich’s chronology but aren’t expert in his work.’

However, none of these responses showed that the interpretation text weakened their appreciation of the exhibition. Borchardt-Hume has commented: ‘Some visitors appeared irritated by certain curatorial choices, yet this did not seem to diminish their overall enjoyment/appreciation (something similar came out of [the] Tanks survey). This suggests that one does not need to please all the time but [that you] must enable visitors to formulate responses’.6

Indeed, the enjoyment and learning experience is often divorced from the audience’s response towards the curatorial interpretation. This was notable in the responses of the Tate Britain audience, not only on the ‘enjoyed’ and ‘didn’t enjoy’ cards but on the ‘surprised to discover’ and ‘never knew’ cards. These cards indicated that many audience members made ‘surprising’ discoveries about Turner despite most of them already being knowledgeable about the artist to some degree. David Brown, lead curator of Late Turner, commented: ‘I was very pleased to see these comments as this shows not only that the audience learned new things but that they were apt to make judgments and become engaged in the argument we wanted to build’.7 Brown explained that the aim of the curatorial narrative was to present a history of Turner’s late work but also to challenge the perception of Turner’s paintings from this time and address how his work and reputation were handled after his death. The responses of the audience to the ‘surprised to discover’ and ‘never knew’ questions showed their reactions of surprise with regard to these ideas, and for Brown, their obvious engagement with the interpretation made the exhibition a success. According to Brown, a curator does not always expect a positive response; rather, he or she aims to make a sufficient impression through the curatorial interpretation such that people talk about it in any way, positive or negative.8 In general, the Late Turner cards revealed that the audience for the show came from a segment rather different to the one that the curators had anticipated would visit. They were surprised to discover that the respondents were not as knowledgeable about Turner’s late work as they had assumed the exhibition’s audience would be.

4.1.2. Exhibition design

Apart from the curatorial narrative and the interpretation texts, visitors commented on the design of the exhibitions, which provided particularly valuable feedback for the SMEs that are often involved in the design processes. Tate Modern participants reported on issues such as the visibility of certain paintings, the loud volume of a film being played in one of the rooms, which distracted the attention of those looking at works in the same room, and the fact that they could not photograph the exhibition:

‘The organisation of room 5 [and the] projection of a recreation of Victory of the Sun is very interesting, but the sound is distracting when looking at Black Square, a piece that requires concentration from the visitor.’

‘Room 9: No point in hanging works so high up the wall. They…could have been omitted altogether.’

There were also comments on the spaciousness of some of the galleries, which for some audience members inspired peaceful contemplation. Tate Britain’s audience commented mainly on the wall colours of the rooms, stating that darker wall colours helped bring out the effect of light in Turner’s paintings, although opinion was divided across the cards:

‘Wall’s colours are too bright in room 1 and yellow too strong in room 6.’

‘The exhibition was very tastefully presented. I enjoyed the wall colours of each room. The paintings were very well lit.’

‘The way the exhibition is set up makes it very easy to follow. The colour of the walls helps with the mood and atmosphere of each room.’

This feedback highlighted what some members of the audience saw as flaws with the design of the exhibitions, which could be taken into consideration by the exhibition curators and designers, in many cases SMEs. For example, if the forecast is that the exhibition will be very busy, allowances might be made, such as making sure the labels which accompany the paintings are legible at a distance.

One further comment was made that ‘The textures of the paint varied so much – wish I had [had] a magnifying glass available!’. This suggests that Tate might consider offering some props that would help enhance the audience’s encounter with specific unique features of works of art. The authors of this paper themselves encountered the exceptionally detailed but extremely small etchings of Turner that might have been better experienced had magnifying glasses been provided. Given the high number of visitors per day, it might be particularly difficult to design such an interaction; nevertheless, the comment offer food for thought.

In the case of Malevich, part of the exhibition hang recreated the experience of the historically important Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 of 1915. In Room 6 several paintings from this exhibition were hung up the wall as high as the ceiling. More knowledgeable visitors were aware of this reference to the original show and saw that it was being done on purpose. Furthermore the results for Malevich indicate that there were many responses on ‘enjoyed’ cards about the works themselves, particularly the installation of the Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10, which provoked a strong emotional response in the audience.

The most notable issue and one that nearly 50% of Tate Britain’s visitors noted was the small font size and the low position of the labels. Late Turner was a very busy exhibition and at any one time there were often more than four people standing around a single painting. As one participant stated:

‘Too many visitors, which is great for Tate, but influences your private experience. Texts are a bit too small for this amount of people, all trying to read it.’

The size of the print and the positioning of the wall texts severely affected access to interpretation and basic information about the work, as well as flow around the exhibition. In addition, some visitors reported that the typeface used for the text was difficult to read, using the word ‘chunky’. Late Turner curator David Brown commented on this:

I’m not surprised about this, as I found the captions difficult to read myself when I saw the format of which the rub-down print arrived. And, that’s without the rooms being crowded and people trying to read them from a distance. My view as a curator is that text should not distract from art – which explains why sometimes it is not placed literally next to each work, but grouped in ways that repeat the hang – but it must be legible and at a readable height for adults as well as children and [for people in] wheelchairs.9

Text illegibility was not a problem reported by most visitors to Malevich, except one comment, which revealed that this might also be a recurring issue for Tate Modern exhibitions: ‘Captions – as usual – too small, too low, and not always clear what they refer to’.

4.1.3. Audioguides

The audioguides for both exhibitions generally received good feedback, and the Tate Modern audience made only positive comments:

‘The audioguide offered very interesting background information and helped contextualise the Malevich exhibition.’

‘The audioguide made the whole experience much more worthwhile, especially hearing from the curator.’

The Tate Britain audience was also generally enthusiastic. However, there was one interesting comment on a ‘didn’t enjoy’ card which read: ‘I didn’t take the audio guide and then spent time regretting that and wondering if I should have. Why not include the audio guide in the price so everyone gets it?’ Since the role of the audioguide is to put the artistic work in context, including it in the price (or perhaps for a small extra fee) may be worth experimenting with since it could enhance the cultural and educational value of the exhibition.

4.1.4. Social interaction

The fact that Late Turner was overcrowded made a negative impression on a small group of Tate Britain visitors. However, other visitors to that same exhibition enjoyed being among Turner fans and enthusiasts. One Tate Britain visitor noted that ‘the contemplative rhythm of the galley crowd actually made viewing the art easier. Very unusual experience’. Along similar lines, a Tate Modern visitor remarked that they ‘mentally surveyed the gender, age, nationality breakdown of the visitors’ to Malevich and that they ‘can stare at exhibits for hours and look like they are having the opposite of fun’. Such comments reveal the importance of the social aspect of the visitor’s experience. It might be worth Tate considering possible visitor behaviours within exhibitions as part of the planning process. Recent research has argued that the behaviour of the museum audience and their experience of museum exhibitions arises in and through their interaction with others.10

One Tate Britain visitor commented that they did not enjoy the fact that ‘you employ interesting people who know about the works in front of them but ask them to be moody security guards rather than passionate educators’. This comment suggests that there is a will for social interaction between visitors and gallery staff on a learning basis. Currently visitor assistants may advise audiences about where specific artworks are located and may possibly give some factual details about specific works, although not in the kind of depth that a formal guide would give. Tate runs organised paid tours led by curators and free tours through the volunteer scheme at specific times during the day, but does not have roaming guides whom audience members may approach during their journey through the exhibition. Our research suggests that Tate could consider offering valuable knowledge to their visitors at the ‘exhibit face’, ‘creating fruitful audience interaction and offering a socially oriented alternative to the personal use of the audioguide’, as one audience member wrote on a card.

4.2. Learning

The ‘surprised to discover’ and ‘never knew’ cards proved to be particularly useful in providing evidence about what visitors learned during their visit. It was also interesting to see that although the two sentences written on the cards could be considered to be very similar in their meaning, every visitor responded differently to each one. The striking difference in the responses to the two questions was that the majority of the audience responded to the ‘never knew’ card with key facts that they had learned through their journey in the exhibition, whereas the ‘surprised to discover’ card triggered additional self-reflection both about the visitor’s overall knowledge in relation to the artist and general comments about art. In cooperation with the Learning department, we decided to categorise the responses of this set of cards using four codes: knowledge about the artist, knowledge about the gallery, knowledge about art, and the visitor’s knowledge about themselves.

4.2.1. The learning process and the audience for Malevich

At Tate Modern visitors reported that they learned about Malevich’s work in painting, theatre and architecture, his influences, his ideas and the creative process behind his paintings. They also learned about the wide range of styles in which he expressed himself, the recurrence of his styles across his work, the hidden painting underneath Black Square 1915, the fact that he was a teacher and other biographical details. Many Tate Modern visitors commented on the artist’s trajectory from figurative painting to abstract and back again as the most ‘surprising’ element of the exhibition. These were clear successes for the curatorial narrative. Putting the journey of the artist in context made visitors, according to a few comments, ‘feel, see, and grow’ with Malevich, a process which they described as ‘emotional’, ‘touching’ and ‘inspiring’. In addition, the chronology helped some visitors increase their knowledge about art and reflect on how this had happened:

‘I was surprised to discover how the influences of other artists were apparent in Malevich’s early work and recognisable to me, and that I could see the difference of the Russian influence from the work and direction of contemporary European artists.’

‘I was surprised to discover how much of a statement a canvas with a black square on it can make. I would have never known it meant so much.’

By contrast, there were only a few comments showing how exhibition visitors to Malevich had acquired knowledge about the museum itself. There were, however, substantial responses about the knowledge that had been acquired through the exhibition about art in general and about Malevich’s specific socio-political context. Indicatively, visitors learned about:

‘The connection between futurism and modern graphic design.’

‘[F]uturism in Russia.’

‘How important the role of women artists was at this time e.g. Goncharova, Rozanova.’

‘The existence of an avant-garde movement uniquely Russian.’

‘The importance of suprematism in modern art.’

‘[that] paper was a rare commodity in Russia.’

‘How much philosophical and political views affect how artists depict their reality.’

The diversity of information visitors learned demonstrates the value of contextualising an artist’s work in the socio-political and art historical context of his or her own time. It also offers an opportunity to design into the exhibition process additional learning elements that visitors will enjoy and appreciate. Although it is clearly a challenge for curators to understand how to capture the emotional and spiritual processes that occur during the visitor experience, our self-reflection cards (‘Did answering our questions affect your experience of visiting the exhibition and, if so, how?’) demonstrated some strong evidence that the visitors gained knowledge about themselves in relation to how they think about art:

‘It made me articulate my ideas into words and come up with an opinion. It made me think in terms of binaries good/bad.’

‘I found the exhibition and the questions made me tap into knowledge of seemingly disparate elements.’

‘I thought about what I was learning about, and how I felt about it.’

The reflection process occurred also with the ‘surprised to discover’ cards, one of which read: ‘I could not stop asking myself that Neville Brody must have taken inspiration to design his fonts and graphics from Malevich’. Imaginative individual and personal reflection was also raised in comments made on the ‘never knew’ cards:

‘[that] Malevich existed. What a strange gap in my knowledge of modern art (now filled).’

‘Malevich’s magnum opus, the “Black Square” was directly inspired (copied?) from Robert Lewis-Stevenson’s 1883 novel “Treasure Island”, with its “Black Spot”, a message to convey death impeding to the receiver.’

The responses on these cards provide evidence that the visitors were encouraged to reflect further at the ‘exhibit face’, which prompted them to be more focused and conscious, forming new kinds of appreciation for what they had been seeing:

‘Yes, made me be more concentrated to all paintings, not just passing by but trying to understand.’

‘Perhaps made me more conscious of my own response to these very moving paintings.’

‘It made me reflect more deeply on the exhibition once I had finished viewing it.’

4.2.2. The learning process and the audience for Late Turner

Almost all of the learning cards completed by the Tate Britain audience were about new things learned about the artist and his late work. The curator’s intention to challenge current assumptions about Turner during the late years of his career and about how his work was handled after his death played very well with the audience, who were knowledgeable about Turner but not to the extent that the curators had assumed. Brown states:

What stands out for me is the surprise people seem to have felt about several aspects of the show: that Turner was so prolific; worked so much in watercolour; used sketchbooks so much; painted such varied subjects; worked so much on a small scale when he is ‘promoted as a large-scale painter’; and finally his character and private life. All this is surprising to me as a specialist and curator, as I’ve always assumed they were axiomatic of Turner’s work. The emphasis people give to these impressions suggests we have a very large audience that is genuinely interested, sympathetic, but relatively uninformed or new to the subject. I’m wondering if we always take this into account enough in what we do.11

There were a handful of responses that revealed that the audience had reflected on what they had seen in the exhibition in relation to contemporary global issues, to their own artistic practice and to art history:

‘Disaster at Sea. The story can be told today, not with convicts but refugees and immigrants. When will we learn?’

‘I never knew how involved I had been in his influence in my own painting.’

‘I was surprised to discover the term “varnishing day” and how interesting white can be.’

‘I was surprised to discover how much [Turner’s] paintings have given rise to historical and philosophical interpretation by art historians (some slightly dubious perhaps).’

5. Synthesising the data and designing future strategies

From the account set out above, the research project suggests that a number of important questions could be addressed by Tate teams responsible for ticketed exhibitions at the two London sites. These are as follows:

1. How Tate might measure levels of individual satisfaction for its exhibition audiences: this could be done in a number of ways, for example by looking at those individuals’ enjoyment, how they value what they have learned, their engagement with the exhibition content and their contentment on the issues of price, service offered and ease of access.

2. The visibility or invisibility of the audience within the planning and organisation of exhibitions across Tate departments: our research suggests that curators could engage more deeply and on different levels with the audience before, during and after an exhibition. From our discussions with the curators once they had been given the audience responses, we concluded that research such as this is extremely valuable for a better understanding of what the audience specific to an exhibition learns and what audience members experience during their visit. Curators can use the collected insights in order to help them empathise with their audiences’ aspirations, desires and expectations. This empathetic connection can offer additional perspectives and ideas for the curatorial process, some of which will involve the audience in novel ways. In addition, the significant information that Tate has already gathered about audience types and clusters can be taken into consideration in the planning process as well as the marketing one.

3. The role of collaborating SMEs in creating audience value through Tate exhibitions, and, in the long term, their significant contribution in changing the cultural landscape through collaborations with large cultural institutions: when we began this project we tested the assumption that all four Tate gallery sites collaborate closely with SMEs and that they contributed significantly to the content and delivery of ticketed exhibitions. However, we discovered that this was not the norm. Not all Tate sites have external creative collaborators and the model adopted for exhibition-making at Tate is that in-house staff deliver most of the content for a paid exhibition. External creative SMEs that do contribute are companies such as frame makers, lighting designers and print and design studios. The work of these companies has its impact on the exhibition design, lighting and physical set-up, which are areas that our research has sought to evaluate as part of the audience experience. However, there are other creative SMEs which have more direct exchanges with Tate’s audience and therefore more impact on the shaping of their experience. These collaborations are found outside the paid exhibitions, for instance in the work of Tate’s Learning department.

Considering our preliminary cross-departmental research and findings, we suggest that the collaborative activity between Tate and creative SMEs is a significant and interesting area for further research particularly with regard to ways in which these SMEs affect Tate’s audience experience, value creation and models of engagement. Meanwhile, some immediate questions related to Tate’s exhibition work with SMEs can be posed:

- Are the collaborating SMEs invited to return to Tate to reflect on the exhibition?

- Is there an institutional process at Tate for feeding back to SMEs to ensure that any negative points are taken into account in future projects?

- Why is collaboration with external SMEs limited in relation to Tate’s exhibition programme given that such collaborations appear to produce clear benefits (as is suggested by our research)?

Our research has indicated that there are some areas in which external creative businesses could have an impact on the audience experience during their visit to a Tate exhibition. These include the provision of experts in the gallery with whom the audience could discuss the artworks exhibited and hiring creative practitioners to conduct a series of free events related to the paid exhibition that serve different audience types based on their levels of knowledge. It is understandable that costs and total income yield are important factors when Tate considers working with external collaborators. However, there are plenty of opportunities for incentivising creative businesses to work with a brand like Tate’s. These businesses can also be considered a part of Tate’s audience and this perspective can open up new and fruitful ways of engaging Tate with the creative sector. The Learning department has taken some steps in this direction with the Circuit project for 15–25 year olds who, as well as being members of Tate’s audience, can also be young artists.12

Several of the insights gained through this project have triggered creative responses relating to assumptions about audiences and exhibition curating. For example, David Brown has questioned the impact of the permanent collection displays on people’s knowledge about Turner: ‘Whether the permanent Clore hang is doing its job as an introduction to Turner, as opposed to exhibitions with particular arguments, is the more important question for me now’. In addition, he will be reflecting on the way the exhibition was finally set up: ‘I will pass on the specific complaints about caption legibility to the relevant teams – they are very important’.13

6. Reflection on the research method

The final element in this report is a reflection on the method we designed and implemented for this short research project. As is evidenced in the self-reflection cards, the majority of the audience members who took part in the research enjoyed the process: having to respond to our questions helped them to concentrate more during their visit, and they responded well to being asked to think critically about what they had seen and to become conscious not only of the works of art but also of the overall design of the exhibition. This suggests that their participation in the research was not disruptive and in fact enriched their experience. Therefore, we consider that the research method we adopted was successful in eliciting the tacit understandings that underpin the audience’s experience throughout the exhibition.

Another observation relating to the method is that the responses to the ‘enjoyed’ and ‘didn’t enjoy’ questions showed that people could describe with more ease and precision the negative parts of their experience than the positive ones. Although fewer in number, the ‘didn’t enjoy’ cards included very concise, detailed descriptions of negative aspects of the exhibition that interrupted the viewer’s immersion in their surroundings, such as the size of the caption texts. In contrast, the ‘enjoyed’ cards included long descriptions of the experience of being at the exhibit face, appreciating art and learning about the artists. This difference is unsurprising given the difficulty of putting emotions into words, even if given plenty of time to do so, and is worth mentioning as part of this methodological analysis for the consideration of those planning similar audience research projects.

The project enhanced social interaction between visitors: the knowledge that they would have to respond to the cards stirred lively critical discussion between the groups of audience members who took part in the survey. Some commented that seeing others with turquoise boxes in the gallery made them feel part of a team, all taking part in a game through which they could help Tate to connect better with its audiences. Here are some such responses from the self-reflection cards for both exhibitions:

‘It encouraged me to examine all the exhibits closely and to reflect on what I found interesting or impressive and why. In other words, what were my favourites and why.’

‘Stimulated thought. Felt more involved in “Art”.’

‘Made me think about what I was seeing. Why is it normally only kids that get activity packs??’

‘It forced me to look closer than we would do normally at the details (reflecting on a meta-level on the exhibitor’s intentions regarding visitor guidance and positioning of the paintings.)’

Although a small number of cards were never returned, a large majority of the people to whom we presented the boxes accepted our invitation to participate and returned the completed cards. We speculate that the nicely designed and presented cards offered the research initiative a status and uniqueness that encouraged Tate audiences to participate. Mentioning that the project was a research initiative also seemed to stir interest, mainly because people were not necessarily aware of the existence of the Research department at Tate.

There was one observation about the usability of the boxes designed for this project that might be borne in mind for future projects. A visitor commented that although the box was light in weight, it might have been better to have used a hanging pouch or bag so that participants could write their comments on the cards in situ more easily and also be able to hold the audioguide at the same time.

Finally, we noted that the cards pinned on the wall at the end of the exhibition stirred a good deal of interest. Participants who were in the process of returning their cards would stay and read other participants’ comments and discuss them with the researcher and among themselves. As David Brown noted: ‘People were pleased to be given some questions to think about, in relation to curation and presentation, or as one said, to feel “involved in art” – a sign perhaps that “art” is sometimes off-putting or distant’.14 While this might not be true for all audience types, it certainly surfaced as a strong view among the knowledgeable audience for Late Turner and it should be taken into consideration when thinking about future audience interaction with the gallery.

7. Conclusion

The biggest challenge for Tate appears to be the initiation of a dialogue with its audience about their needs, aspirations, desires and expectations. Not every visitor will want to co-curate an exhibition, but different groups within Tate’s overall audience will have different thoughts on how they would like to shape their relationship with the gallery and the brand. Our research suggests that there are opportunities for developing different kinds of relationships, social experiences and appreciation for the gallery and for art in general. There are current attempts to engage parts of Tate’s audience by means of digital projects (for example, encouraging visitors to post a picture online with a Tate hashtag); however, such projects work better as complimentary forms of communication than as means of setting up primary channels for dialogue, which might in turn impact upon exhibition design and curating as well as contributing to marketing initiatives.