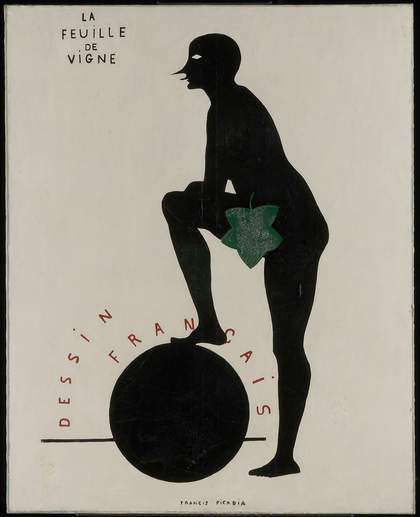

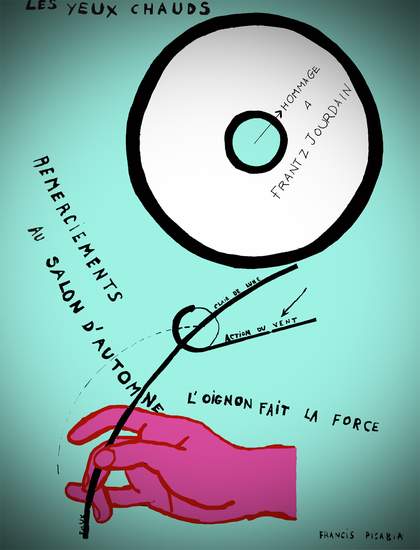

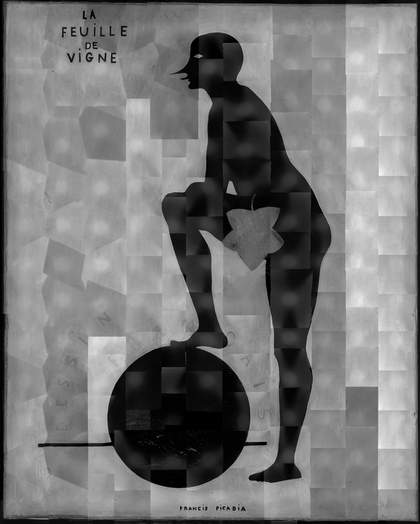

Fig.1

Francis Picabia

The Fig-Leaf 1922

Oil paint on canvas

200 cm x 160 cm

Tate T03845

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017

The Fig-Leaf (fig.1) is an immensely complex work, despite the disarming simplicity of its appearance. Physically, it consists of multiple layers of paint applied over an earlier work – Hot Eyes 1921 – and has variously been described as having been painted in enamel paint, oil or Ripolin, which is a commercial brand of glossy housepaint. The gloss, wrinkling and dense colouration of the paint are characteristic of Ripolin housepaint rather than artists’ paint, but as artists’ paint and commercial house paint were both oil-based in the 1920s it had previously been difficult to identify this material positively.1 Picabia did not reveal much about his materials and techniques in his writings, and photographs of him in the studio tended to be carefully choreographed.

The image in The Fig-Leaf is figurative, yet it resists straightforward interpretation. Picabia drew on classical sources – both ancient and as manifested in nineteenth-century French art – incorporating references which would not have been lost on the contemporary public. He also loaded the work with dada impudence, painting over an earlier notorious mechanomorphic work with characteristic chutzpah and redisplaying the canvas within a year, writing in large bright letters in the main body of the painting, and drawing attention to the main feature of the work, the fig leaf, by the inscription in the top-left corner.

The acknowledged sources of the earlier painting and The Fig-Leaf are examined in this study with regard to the historical context in which they were created and received. The results of analysis of the materials and techniques used by Picabia in these two works will also be presented, along with an assessment of how the materials themselves have aged.2

Hot Eyes: conception and reception

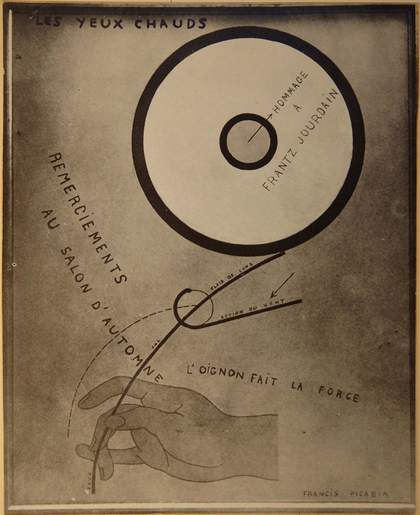

Fig.2

Photograph of Hot Eyes 1921 from the Album Picabia

Reproduced with the generous permission of the Comité Picabia

Photo: Suzanne Nagy

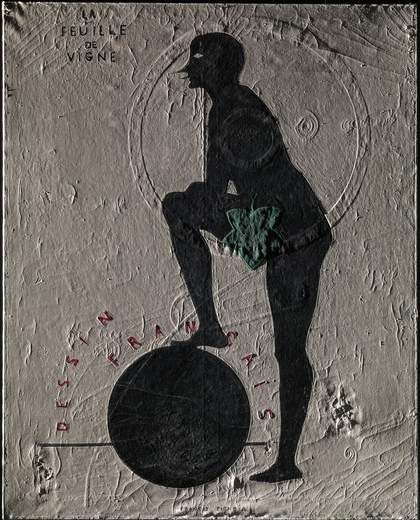

Fig.3

The Fig-Leaf 1922 under raking light from left

Photo © Tate

There is a photograph of Hot Eyes (fig.2) in an album of cuttings and photographs made by Olga Mohler Picabia, the artist’s second wife and devoted companion for the last twenty-five years of his life.3 She dated the work 1918 in her album, but it is generally acknowledged to have been created and certainly first exhibited in 1921. With knowledge of the appearance of Hot Eyes from this photograph, the continued existence of the first painting becomes more apparent beneath the surface of The Fig-Leaf when the painting is viewed in raking light (fig.3).

Hot Eyes was a mechanomorphic work and caused controversy when it was first exhibited at the official Salon d’Automne in Paris in November 1921. Picabia’s interest in machines had first been expressed in an anonymously written interview with an American newspaper in 1915, wherein he claimed that:

This visit to America … has brought about a complete revolution in my methods of work … prior to leaving Europe I was engrossed in presenting psychological studies through the mediumship of forms which I created. Almost immediately upon coming to America it flashed on me that the genius of the modern world is in machinery and that through machinery art ought to find a most vivid expression.4

The importance of the machine in contemporary imagery and thinking was expressed by the writer Paul B. Haviland in a statement in the magazine 291 in 1915, where he described the machine as a ‘daughter born without a mother’.5 This phrase had been used several months earlier by Picabia as the title for his first work associated with the mechanomorphic style, which the Picabia scholar William Camfield attributed to 1915.6

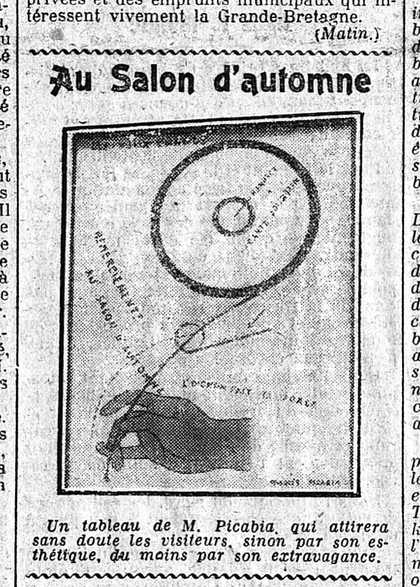

Fig.4

Hot Eyes 1921 illustrated on the front page of Le Matin, 1 November 1921

Gallica, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Source: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k573774m.item

Machines quickly became part of everyday existence in the early twentieth century: domestic appliances were becoming part of every household, X-radiography and radiation-based treatments (today called radiotherapy) were revolutionising medical science, automobiles and aeroplanes were commonplace, while the First World War led to the invention of killing machines, capable of slaughter on a massive scale. Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, Picabia’s first wife, commented on Picabia’s use of machines in his paintings:

Picabia, who at first extracted a profuse plastic inspiration from machines, adopts thereafter aspects which are directly photographic; but emptied of their utilitarian signification, Picabia charges them with a new reality, of which he alone is the arbiter, creating an atmosphere of migration which surrealism systematised.7

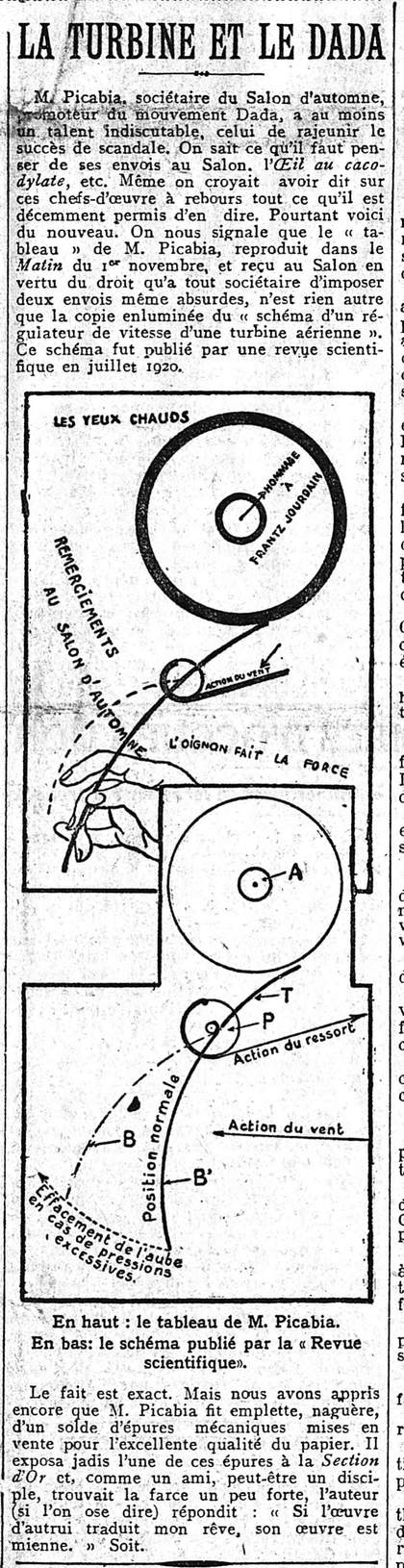

Fig.5

Article on front page of Le Matin, 9 November 1921, comparing Hot Eyes to a diagram of an air brake turbine

Gallica, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Source: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5737826.item

Hot Eyes appeared on the front page of the French newspaper Le Matin on 1 November 1921, accompanied by the text ‘A painting by M. Picabia which will no doubt attract the visitors, if not by its aesthetic, at least by its extravagance’ (fig.4).8 It had barely been hung for a week in the Salon d’Automne when an anonymous journalist published an article in the same newspaper revealing that Picabia had based his composition on a diagram of an air brake turbine reproduced in the journal La Science et la Vie (fig.5).9 Picabia’s reaction was swift and searing: ‘So Picabia has invented nothing, he just copies. But of course, Picabia copies an engineer’s sketch instead of copying apples. Copying apples is something everybody understands, copying a turbine is stupid’.10

Picabia had been elected as an associate of the Société du Salon d’Automne in 1912, shortly before he emerged as a controversial member of the avant-garde. As an associate, even a former associate, he could not be excluded from the annual exhibitions, and this he exploited to the full during his dada years (1915–1921).11 At the Salon of 1919 the dadaist paintings had been hung under a stairway, but after Picabia made a public rumpus, the critics sought them out to write acerbic comments about them. Frantz Jourdain, President of the Salon, tried to quell the negative publicity that had resulted from this dispute, and from the subsequent year’s showing of dadaist works, by appointing Picabia to the hanging committee of the Salon in 1921. Jourdain also moved all the dada works to a major room where they could be seen from the entrance of the Grand Palais and even spoke to reporters about the Salon’s new motto: ‘Evolve or perish’.12 However, Jourdain’s plan rather backfired, as before the exhibition even opened a rumour went around that Picabia would send an ‘explosive’ painting. The public took it literally, fearing some sort of terrorist action, and Jourdain had to publish an announcement stating that there was nothing to fear and that such rumours were unfounded.13 Hot Eyes sported the words ‘Hommage à Frantz Jourdain’ (Homage to Frantz Jourdain) and ‘Remerciements au Salon d’Automne’ (Thanks to the Salon d’Automne) but it also has the phrases ‘clair de lune’ (moonlight), ‘action du vent’ (action of the wind) and ‘faux’ (fake or false). The more prominent phrase ‘l’oignon fait la force’ is also inscribed. It is possibly an ironic inversion of ‘l’union fait la force’ or ‘unity is strength’, a national if not nationalistic motto made farcical by substituting the word ‘unity’ for ‘onion’. Camfield also suggested that Picabia was making a simple reference ‘to the attention accorded something (someone) with a strong odour’.14 The superficial homage paid to the Salon and its President is somewhat undermined by these farcical phrases, which, combined with the depiction of a mechanical way of controlling air flow, suggest that Picabia’s intention was to deflate the pomposity of nationalist and establishment rhetoric.

1921 was the year that Picabia finally split from the dada movement and there was a poisonous atmosphere between him and some of the members of the dada group. In March 1921 Picabia developed a painful eye disease and had withdrawn from public gatherings in a depressed state. His partner Germaine Everling described his mental and physical anguish:

For thirty days and thirty nights he remained in a lamentable state … the doctor … to relieve the pain prescribed granulated aconitine, a drug with which it is difficult to get the dosage right and possessing effects that vary according to the patient’s temperament. The doctor warned us to pay great attention to whatever symptoms it might produce and Picabia, apprehensive as always, developed a superstitious fear of the little box, though at the same time attracted by the relief it gave him.15

Several images by Picabia on the theme of eyes appear at this time. His other submission to the 1921 Salon d’Automne was The Cacodylic Eye. Cacodyl is a compound of arsenic and this toxic material was used in pesticides and is a known irritant to eyes. The work consisted of signatures, photos, collaged elements, painted aphorisms and rude comments added by fifty-six of Picabia’s friends and acquaintances who visited him during his illness. Picabia considered it finished when there was no more room on the canvas. As Picabia scholar Maris Lluisa Borras has argued: ‘These two pieces gave rise to more talk than all the other works in the Salon put together. Here was a fresh paradox: as Francis Picabia’s position became more and more definitely independent of the Dada group, his personality continued to be more undeniably and obviously the most radically Dadaist of them all’.16

Technical analysis of Hot Eyes

Fig.6

Reverse of canvas showing strainer

Photo © Tate

Fig.7

Detail of loosely woven, rough-cut canvas on the reverse side

Photo © Tate

Hot Eyes is painted on a large, non-standard sized strainer (fig.6), which is possibly original. The coarse and loosely woven canvas, which is 14 warp by 11 weft threads, seems to have been hand-cut with scissors and has unprimed borders on three sides at the reverse (fig.7). It may have been stretched larger originally, and primed with pale grey. The priming seems to have been applied by brush and the border of the priming that worked through to the reverse is uneven and does not appear to have been applied by an artists’ colourmaker.

Fig.8

Detail of top edge showing tack, torn canvas and cotton tape reinforcement

Photo © Tate

The attachment to the stretcher has been altered and augmented several times, with rusty ferrous tacks widely spaced. The canvas is of poor quality and is now extremely brittle due to natural ageing. There is a selvedge at the lower edge of the work and at the top edge the fabric is roughly cut, with a border of fabric which is not primed.17 The vertical edges have a more generous margin of fabric overlapping the foldover edge onto the reverse. The left side has been cut into the primed area whereas on the right-hand side the priming stops short of the edge of the fabric and the excess material has been folded underneath. The original stretching is sparse and uneven leaving the canvas slightly slack and undulating.18

The top-right corner is poorly folded and torn (fig.8), which suggests that the canvas has been re-stretched at some point. The poor quality of the canvas, the uneven, brushed application of the grey priming and the non-standard size for the strainer indicate that this is not a standard commercially prepared support, but more of a hand-made ensemble. In isolation this could perhaps be interpreted as a deliberate choice by Picabia to use non-fine-art materials.

It is interesting to note that in his interview with an American newspaper in 1915 Picabia emphasised that line took precedence over colour in his more recent work: ‘Naturally, form has come to take precedence over color with me, though when I began painting color predominated. Slowly artistic evolution carried from color to form and while I still employ color, of course, it is the drawing which assumes the place of first importance in my pictures’.19

Fig.9

Detail of border showing turquoise paint

Photo © Tate

Fig.10

Detail of loss in white paint revealing turquoise underneath

Photo © Tate

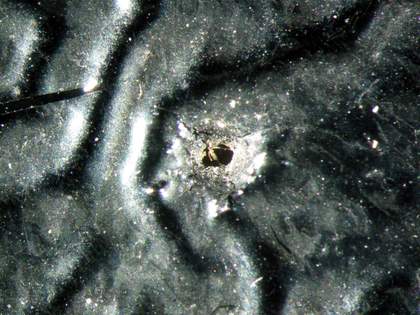

Fig.11

Detail of reverse of canvas where turquoise paint has seeped through hole

Photo © Tate

Lines are clearly essential to replicating an engineering diagram, but close examination of Hot Eyes and contemporary comments seem to suggest that colour may have been a particularly important feature of this work. The only photograph of the painting is in black and white (see fig.2) and it has always been tacitly assumed that Hot Eyes was painted in black and white, or at least in colours similar to those in The Fig-Leaf. However, once out of its frame, a turquoise border can be seen at the edges beneath the upper layers of white (fig.9). On close examination, glimpses of this turquoise colour were evident where the border of the white met the outline of the black legs, and can be seen where losses have been incurred in areas of the white paint (fig.10). In the centre of the target-like circles at the top of Hot Eyes there is a hole made by compasses used to create the circles. On the reverse, turquoise paint has seeped through this hole and dried in a small circle (fig.11).

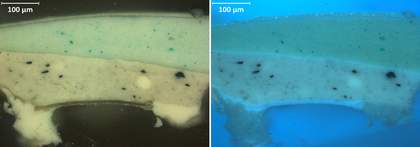

Figs.12a–b

Cross-section of paint from upper-right edge in visible light and ultraviolet light

Photo © Tate

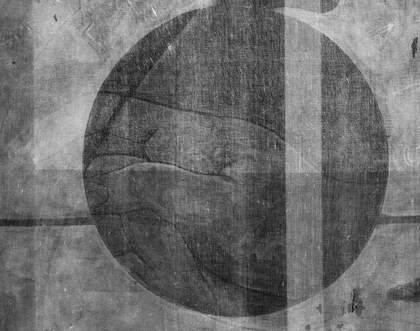

Fig.13

Detail of digital X-radiograph of the hand from Hot Eyes beneath the ball of The Fig-Leaf

Photo © Tate

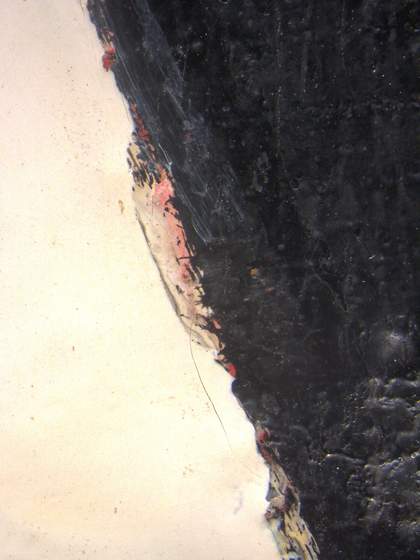

The layer structure is visible in cross-section (figs.12a–b). In the lowest layer there is a white ground, then a grey coloured priming, over which lies a layer of the turquoise colour. Above the turquoise there are several layers of white, but only traces of the upper white are visible in this section. From glimpses of colour at the borders of the ball, it seems that, in addition to the turquoise, there are areas of pink which coincide with the hand shown in the in X-radiograph (fig.13). At first it was thought that the border of the hand was black, but microscope examination revealed glimpses of bright red paint (figs.14a–b).

Fig.14a

Detail of left edge of ball, showing glimpses of red and pink paint

Photo © Tate

Fig.14b

Detail of lower-right edge of ball, revealing pink paint under a loss

Photo © Tate

Other clues that the painting may have been brightly coloured can be found in the article in Le Matin from 1 November 1921, where it was described to be extravagant. The second article in the same newspaper on 9 November described the painting as an ‘illuminated copy’ of an air brake turbine. The word ‘illuminated’ is reminiscent of illuminated manuscripts painted in bright colours. It is not possible to see what colour the letters may have been from detailed surface examination, but it seems that Hot Eyes was a vibrant addition to the Salon, of monumental size and painted with turquoise, pink, red and possibly other loud colours (fig.15), which may have added to the sense of outrage it provoked.

Fig.15

Diagram of Hot Eyes showing known elements of colour scheme

Photo © Tate

Image: Annette King

Not only were the colours of dazzling hue, but they were purportedly painted with commercial paint. Ripolin was a high-quality example of house paint used by some artists. Contemporary and later commentators gave some insight as to why Picabia chose to paint with Ripolin gloss colours. For example, the artist Marcel Duchamp, writing under his pseudonym Rrose Sélavy, remarked in 1926 that Picabia’s ‘concern for invention leads him to use ripolin instead of sanctified tube paints, which, in his view, take on too rapidly the patina of posterity. He loves the new, and his canvases of 1923, 24 and 25 have this aspect of fresh paint, which keeps the intensity of the first moment’.20 In 1964 art historian Michel Sanouillet described how Picabia felt the need to innovate and introduce new materials into his work:

Picabia felt … that the machine had accomplished its conquest of man … that his diagrams had ceased to inflame the anger of the bourgeois … The Eiffel Tower whose unaesthetic carcass had offered material for so many controversies … was now part of the Parisian landscape. This is why new elements appeared in the painter’s work from 1919: collage, the use of solid objects, materials reputed to be non-artistic, like Ripolin.21

The layer of turquoise paint in Hot Eyes was found to consist of a drying oil, zinc oxide, chrome oxide green, and a metallic drier.22 A good match was obtained with genuine Ripolin shades from the period 1929–46: Ripolin Bleu Azur Pale, or Ripolin Bleu Turquoise Clair.23 It was not possible to take samples of the pink and red paint in Hot Eyes, so their composition and paint types remain unknown.

The Fig-Leaf: history and meaning

Having no doubt relished the attention he received by exhibiting Hot Eyes in 1921, Picabia took advantage of the work’s notoriety and recreated it, painting over it with an entirely different composition in 1922. What is even more extraordinary is that he seems to have done so without taking the painting out of its frame. The frame around The Fig-Leaf today appears to be original and there are traces of white paint around the inner edges from this reworking.

One of the mainstays of dada ideology was the destruction of the old and the creation of the new, eliminating all reference to the past. According to art historian Arnauld Pierre, one of the defining characteristics of dada was ‘its systematic opposition to the cultural ideology of its time and more especially to its nationalist dimension’.24 Picabia scholar William Camfield has pointed out that the act of painting The Fig-Leaf ‘involved a Dadaist gesture rarely matched by any of his fellow artists: Picabia painted it over Les Yeux Chauds, completely effacing that notorious work and asserting again the primacy of “life now” over attachments to the past. The painting-over of earlier compositions became common in Picabia’s career from this date onward’.25

After the chaos of the war, there was a fine art movement known in France as le rappel à l’ordre (the return to order). Like the term ‘avant garde’, ‘le rappel à l’ordre’ is a French military expression that was appropriated to aesthetics, in this case by writer Jean Cocteau, who used it as the title of a collection of nationalist essays he had begun in 1918 and published in 1926.26

Fig.16

Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres

Oedipus and the Sphinx 1808

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Fig.17

Hermes Tying his Sandal

Roman copy, 2nd century AD, after Greek original, 4th century BCE

Musée du Louvre, Paris

One of the central reference points of the French nationalist elite was the nineteenth-century classicist painter Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres. A new wing dedicated to classical French artists had recently opened at the Louvre, and Ingres had become a great national symbol of French tradition. Picabia’s life-sized silhouette of a nude figure in The Fig-Leaf is widely acknowledged as being based on Ingres’s painting Oedipus and the Sphinx 1808 (fig.16), which curator Jens M. Daehner has argued may itself refer to an ancient Roman sculpture in the Louvre, the imposing statue of Hermes tying his sandal (fig.17).27 However, Picabia reversed the position of the limbs in his figure, raising the right leg onto the ball, reverting to the original position of the Hermes sculpture and thus potentially revealing the figure’s genitalia. In Ingres’s painting, Oedipus is delicately arranged to keep any unseemly details conveniently hidden from view by the positioning of his legs. By adding a fig-leaf, Picabia was making obvious the prudery of classical art, which relied on the careful placement of limbs to make nudity acceptable, and the conservatism of the Salon and public alike. In the 1920s it was still the custom in antiquities museums to display nude statues like Hermes with plaster, tin or bronze fig leaves attached. As Daehner points out: ‘just as the fig leaf covers the man’s crotch, the painting as a whole covers … Hot Eyes. By over-painting the criticized work and adding a fig leaf, Picabia also playfully points a finger at the censorship of his work by the Salon des Indépendants, for which two out of his three submissions had been refused in Jan 1922’.28 Daehner also notes that ‘by choosing to replace an abstract work centered on a machine with a traditional figurative scene Picabia also ridiculed the contemporary trend of classicizing styles and subjects. The monochrome silhouette of a body in profile in Fig Leaf echoes the black figure technique in Greek vase painting of the 6th century BC’.29

Ingres’s famous assertion that ‘drawing is the probity of art’ seems to have been Picabia’s particular target, seemingly reversing his sentiments about the importance of drawing in his own work, expressed in the newspaper article of 1915.30 This is made plain with his inscription ‘DESSIN FRANÇAIS’ (FRENCH DRAWING) in bright red letters around the central ball. It was particularly French drawing to which he was referring and this could perhaps be related to a comment made by the writer André Gide who asserted in 1919 that France was ‘the great school of drawing for the whole world’, while daring to affirm that Germany ‘which does not feel the peculiarities of any beings or any thing, has never known how to draw’.31 It was perhaps nationalistic blindness that led Gide to overlook famous German draughtsmen including Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach and Hans Holbein.32 In 1920 Picabia summed up his dislike of Gide: ‘If you read André Gide aloud for ten minutes, your breath will stink’.33

While making an unmistakable reference to the revered master of French drawing, Picabia removed any reverence by giving the figure a pointed nose in the tradition of street and circus performers or harlequins. He also concealed with paint all drawing on his canvas, and the use of Ripolin commercial paint further undermined the cherished values of fine art.

Technical analysis of The Fig-Leaf

Fig.18a

Detail of hole made in centre of ball made using compasses

Photo © Tate

Fig.18b

Detail of black stain on reverse of canvas where paint has seeped through

Photo © Tate

When Picabia began painting over Hot Eyes it seems that he painted the shapes of the figure and the ball in black first, then added the white up to the borders of these features. At the centre of the ball there is a hole made by a pair of compasses and at the reverse black paint has seeped through the hole creating a small circular stain on the canvas (figs.18a–b). This suggests that the black paint was the first colour to be applied in the area where the hole was made. There is also evidence that the black paint was applied to the surface of Hot Eyes directly, because the turquoise paint can be glimpsed at the edge of the leg between the black and white borders (fig.19). Close examination of the contours of the face shows that the white has overlapped the black in places, as can be seen in the tip of the upper lip (fig.20).

Fig.19

Detail of turquoise paint visible between the black leg and white background

Photo © Tate

Fig.20

Detail of upper lip showing white paint overlapping black paint

Photo © Tate

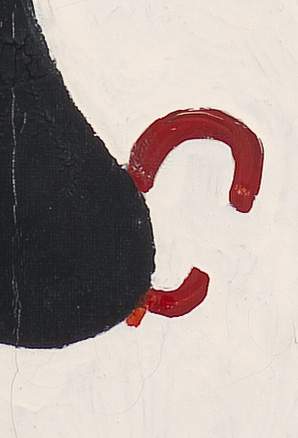

Having painted the black and then the white up to the border of the black, Picabia added the lettering. The red letters were painted on top of the first white layer, as can be seen from the letter ‘C’, which was shaped around the heel of the figure (fig.21). A small loss in the corner of the letter ‘E’ of ‘DESSIN’ shows the turquoise paint beneath, then a depth of white paint at the edge of the loss with the red above it. The upper layer of white goes over the edge of the red and into the loss (fig.22). The second red letter ‘A’ of the word ‘FRANÇAIS’ was sampled and the paint analysed: it contains chalk, PR3 (a synthetic organic pigment known as toluidine red), lead chromate and barium sulphate, which matched well with Ripolin Andrinople Foncé 9. Like the letters of the title inscription, these letters seem to have been painted on top of the first white layer and later layers have been painted around them.

Fig.21

Detail of letter ‘C’ shaped around heel of figure

Photo © Tate

Fig.22

Detail of letter ‘E’ showing loss

Photo © Tate

The corner of the letter ‘F’ from ‘FEUILLE’ shows at least three layers of white, the first underneath the black, then a layer painted up to and over the borders of the black and finally a thicker, brighter layer up to and around the letter leaving a border of the underlying white visible. The first two layers of white contain oil with white zinc oxide and traces of a metallic dryer, which is compatible with Ripolin Blanc de Neige 1 from the period. The later, much brighter layer of white was found to consist of an oil-modified alkyd medium containing titanium white; the implications of this for dating are noted later. The black paint contains oil and a small amount of natural resin and the pigment is carbon black: this combination is compatible with the re-working of 1922. The Ripolin sample of Noir d’ivoire 5 is a good match for this paint.

Fig.23

Detail of short-wave infrared image showing signature of The Fig-Leaf in centre and the fainter signature of Hot Eyes in lower-right corner

Photo © Tate

Image: Kate Dooley

Fig.24

Detail of letter ‘N’ from signature showing marbling of paint

Photo © Tate

The signature moved from the lower-right corner of Hot Eyes to the lower-centre of The Fig-Leaf. This is just discernible in the short-wave infrared image (fig.23). From close observation the letters of the signature were painted on the middle layer of white paint, when it was still wet, giving the letters a marbled appearance where they have picked up the fluid white paint beneath (fig.24).

Fig.25

Detail of fig-leaf

Photo © Tate

The fig-leaf was painted in a glossy green paint which wrinkled richly but unevenly as it dried, leaving some flat glossy areas in the stem and around the edges (fig.25). It seems from the indentations around the fig-leaf that Picabia left a space for it, rather than just painting over the wet paint layer beneath. The green paint contains lead chromate, Prussian blue, chalk and a trace of barium sulphate, and it is good match to Ripolin Vert Irlandais Foncé 82. The flatter areas around the outer edges seem to lie over black paint in places. Black paint is known to dry slowly and often has added driers. The overlying green may have benefitted from such driers in these areas, and dried smooth. But where it does not overlie the black and/or it is thick, as it is in the centre of the leaf, it has dried with large-scale wrinkles. The dark green oil paint contains traces of natural resin in its oil medium, which would hasten its drying. When quick-drying oil paint is applied thickly, the surface dries first and forms a skin. The body of the paint takes much longer to dry, and as it dries it contracts and pulls the dried ‘skin’ of paint on top into large wrinkles. This is the likely cause of the extreme wrinkling evident in the centre of the fig-leaf, the red paint of the lettering, and in many of Picabia’s other so-called Ripolin paintings. It is possible that the fig-leaf was applied with the painting lying flat, as there are no drips or sags in this very thick layer of paint. There was a type of paint available at the time designed to form this sort of wrinkling pattern, and to give a similar appearance wherever it is applied.34 It is not known whether Picabia knew that the wrinkles would develop – although he clearly knew the properties of his materials intimately – nor whether he saw the wrinkling in his lifetime. The very use of Ripolin demonstrates how far his materials were from those of the ‘fine art’ ideal.

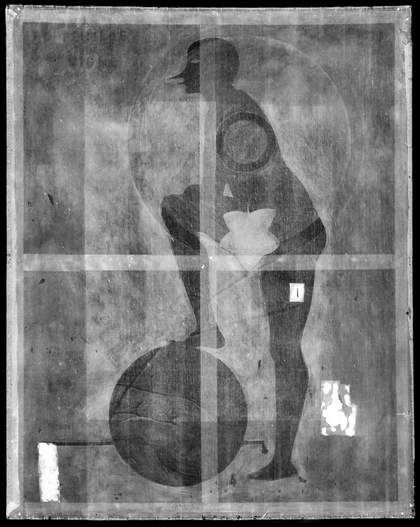

Fig.26

Digital X-radiograph of The Fig-Leaf 1922

Photo © Tate

Fig.27

Short-wave infrared image of The Fig-Leaf 1922

Photo © Tate

Image: Kate Dooley

Fig.28

Detail of tear in leg filled with black paint

Photo © Tate

The ultimate irony of the fig-leaf is that there appears to be nothing hidden underneath it. The X-radiograph (fig.26) and the short-wave infrared image (fig.27) revealed nothing but an empty space. This is perhaps an indirect reference to an earlier theme in Picabia’s work. In 1920 he had created a volume of poems entitled Unique Eunuch. The title is an example of a type of poem described as ‘words without language’, where, according to Picabia scholar Maria Lluisa Borras, ‘he juxtaposed words by reason of phonetic similarity rather than meaning, calling into question the relationship between poetry and communication, which aroused the wrath of the literary critics’.35 The title also appeared on a painting called Unique Eunuch Ivy in 1920, an abstract work of biomorphic cell-like forms with the words ‘unique eunuch ivy’ in the centre and ‘Machine Co.’ on one side. As Borras has pointed out, ivy is an hermaphroditic plant (one that has both female and male characteristics), and the machine reference relates to Picabia’s concept of the artist in the age of machines as a god-like creator producing ‘daughters born without mothers’.36 Perhaps the pointless fig-leaf and the sexless figure are an oblique reference to the mechanomorphic painting underneath, as well as to the pointless impotency of the censoring of modern art.

At some point The Fig-Leaf was damaged quite severely, incurring several tears and areas of broken paint. The repairs were rudimentary and the tears had patches stuck to the reverse with paint that looks like it contains lead white judging from the X-radiograph, because they show up as bright opaque white (see fig.26). The losses and tears at the front of the painting necessitated a new coat of paint to cover them, the losses being simply filled up with this paint, which was liberally applied (fig.28). Where there were holes around the edges, the paint filled them and had the effect of sticking the canvas to the strainer bars (fig.29). This has made any structural conservation treatment of the painting problematic, as the canvas cannot be removed from the strainer without breaking the paint layer.

Fig.29

Detail showing torn canvas attached to strainer bar with paint

Photo © Tate

Analysis suggested a good match with Ripolin Express Blanc 1001, which is an oil-modified alkyd containing titanium white pigment. The date of this later reworking cannot be ascertained as yet. The alkyd and titanium white formulation point to a later date of application, possibly even after the Second World War, as neither component was in common use in commercial paints until the later 1940s and 1950s. This begs the question as to whether it was applied by Picabia himself, who died in Paris in 1953.

Conclusion

The study of this painting, as complicated in layer structure as in layers of meaning, has revealed a work that marked a turning point for Picabia − one of many in his career. On this canvas he painted two works, one taking its sources from a diagram of a machine, a continuation of his dada work, while the other parodied a renewed national interest in classicism and featured a figure referring mockingly to a revered painting by Ingres. He was serious in his political opposition to the nationalistic triumphalism that followed the First World War, yet he did it using humour as a powerful weapon. As a part foreigner himself, he never bought into the greatness of the French nation, and never lost sight of the need to look forward rather than back. This extended to his materials, and he found that the best way to undermine the conservative idealisation of drawing and the line was by dispensing with it entirely, using a poorer quality canvas and commercial paint for both Hot Eyes and The Fig-Leaf. The 1921−2 paints suggested by the analytical results are Ripolin Blanc de Neige 1, Noir d’Ivoire 5, Andrinople foncé 9, Bleu Turquoise Clair 71 and/or Bleu Azur Pale 61, and Vert Irlandais Foncé 82, some of which are shown in the Ripolin brochure. A later layer, possibly of Ripolin Express Blanc 1001 alkyd and titanium white paint, was added perhaps after the Second World War, although not necessarily by the artist, in response to accumulated physical damages.

Close examination of the whole structure of the painting has revealed that Hot Eyes, exhibited in 1921, was an extravagant, colourful work. Time has almost certainly exaggerated the visible presence of Hot Eyes underneath The Fig-Leaf, with the differential wrinkling of paint over the lines of the circles and the red outlines and pink flesh of the hand, but its incompletely masked messages are likely to have been Picabia’s private joke at the time, for as William Camfield and Candace Clements have argued, ‘Insofar as is known, this act of destruction and re-creation was not documented at the time, and went unperceived for decades’.37 But the fact that Picabia repainted it within the frame, leaving glimpses of the original turquoise colour at the very edges as well as at the contours of the figure, suggests that maybe he was playfully drawing attention to its presence. The raised contours of that mechanomorphic painting may well also have been present in in 1922 when The Fig-Leaf was newly painted. As it approaches its one-hundredth year, the painted canvas becomes ever more friable, and the paint films are brittle and fragile. The oil-based white paint of the reworking is also becoming more transparent, an effect of natural ageing, giving a hint of the turquoise colour beneath. All these physical changes only serve to emphasise the presence of the former painting.

Later paintings in the Tate collection by Picabia – including The Handsome Pork Butcher c.1924–65, c.1929–35 and Portrait of a Doctor c.1935–8 – are also what was described by Picabia’s later wife Olga Mohler Picabia as ‘destroyed’, or in these cases, painted over. Although both these later paintings were fundamentally altered, Hot Eyes remains unique in the extreme nature of its re-invention, both in terms of its physical change but also its change of references. As Camfield has written, in The Fig-Leaf we find Picabia’s ultimate dada act of renewal, seeking the ‘now’, taking delight in the visible destruction of what went before, but all the while harnessing its lasting power as a statement of his intentions.38