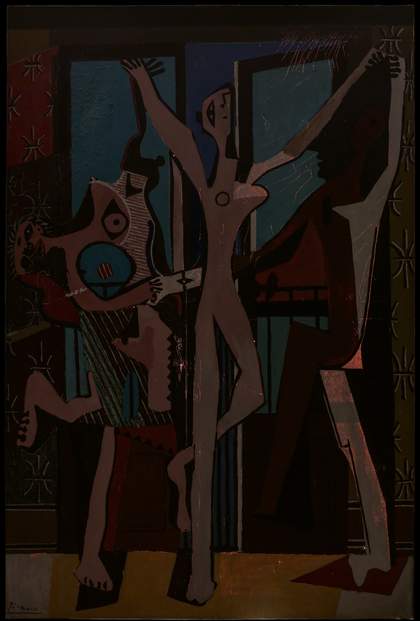

Fig.1

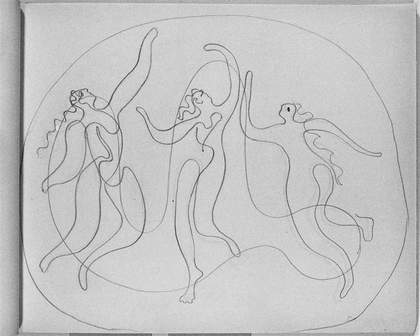

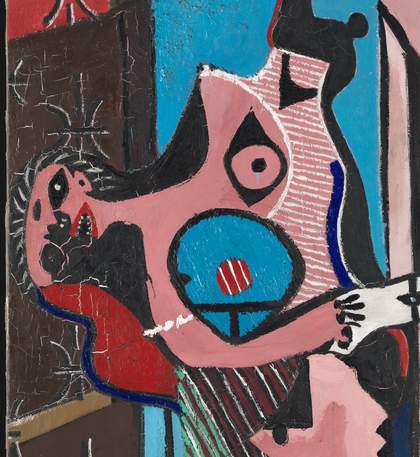

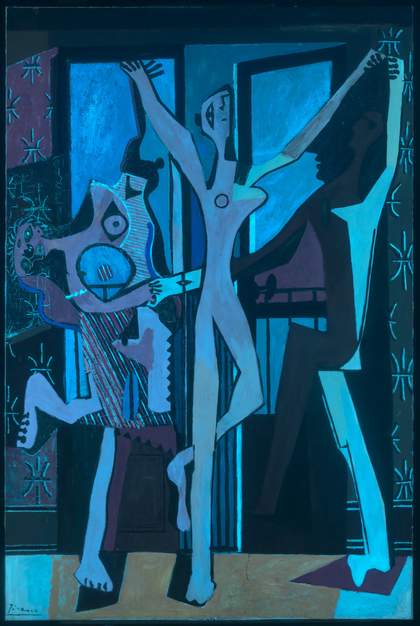

Pablo Picasso

The Three Dancers 1925

Oil paint on canvas

2153 mm x 1422 mm

Tate T00729

© Succession Picasso/DACS London 2017

The Three Dancers 1925 (fig.1) is considered to be one of Picasso’s greatest masterpieces. The moment the artist applied the final touch, the writer André Breton all but begged him to allow him to publish it in his journal La Révolution surréaliste. Picasso was the most celebrated contemporary artist of the time, and this painting became revered immediately. Despite pressure from his dealer and from friends to sell it, Picasso kept it in his possession for forty years, lending it occasionally to exhibitions – notably the Tate Gallery’s major retrospective in 1960 – but he guarded it as his own.

Tate’s acquisition of this painting in 1965 was hard-won by Sir Roland Penrose, a trustee of the gallery and a friend of Picasso’s. The campaign by Penrose to persuade Picasso to sell it to the Tate is well documented in Penrose’s personal notes and later in a publication by Tate curator Ronald Alley detailing what he had to go through to win it.1 This lengthy story will be touched on briefly as some of the discussion between Penrose and Picasso reveals the artist’s thoughts on the painting.

Much has been written about this painting and many minds have been applied to examine its style, significance and symbolism. Some insightful technical analysis was carried out when it was acquired, which focused on the original structure of the painting and stretcher. This analysis is invaluable now since the original stretcher was replaced in 1979. Pentimenti visible in the surface of the painting, especially when viewed in raking light, suggest that Picasso made changes to the painting over time.2 An incomplete X-radiograph made in 1973 revealed for the first time three more conventional dancers beneath the painting’s surface.3 These figures have since been convincingly compared to an earlier tiny painting, now of unknown location, called The Dance painted in 1923. The similarities and differences between these two paintings will be explored in depth here, while focusing in detail on the construction and materials of the Tate painting.

The Three Dancers had been exhibited for many years without glazing before it arrived at the Tate conservation studio in 2012 for surface cleaning. At that time, a new film-based X-radiograph was made to uncover areas not included in the first partial one. The results were intriguing, but it was only with the later support of the Clothworkers’ Foundation that deeper analysis of the painting could be undertaken. The Foundation Fellowship, which supported technical research between 2014 and 2016, allowed time to examine and reflect on the painting with a number of Picasso scholars, carry out photography, explore the images and to undertake new analysis, as well as thoroughly review existing analytical findings. The painting was examined microscopically, making it possible to unpick further the technique and layer structure. The newly discovered order of paint application – what Picasso chose to conceal and what he chose to leave visible – has raised new theories about the date and genesis of the work beneath. The visual information gained from this new research provides further glimpses of the work which Picasso changed so dramatically in 1925, and has generated new knowledge about this arresting and enigmatic masterpiece.

History and context

In the summer of 1960 the Tate Gallery hosted the first major retrospective of Picasso’s work in Britain. It opened in July and by the time it closed in September more than half a million people had seen it, a record number for the time. The day after the exhibition closed the Times reported that ‘The Trustees of the Tate hope to retain one of the paintings on loan permanently for the gallery if there is sufficient public support’.4 Penrose, who was a Tate trustee and surrealist artist in his own right, was given the challenging task of persuading a reluctant Picasso to part with The Three Dancers, which both of them regarded as a masterpiece on a par with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907 (Museum of Modern Art, New York).5 The persuasion took almost five years of assiduous attention and the battle was almost lost in 1964 when Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s former partner and muse, and the mother of two of his children, published her memoirs. Picasso was devastated by this betrayal of confidence, and malicious but unfounded gossip had reported to him that Penrose had been seen socialising with Gilot at the opening of the Maeght Foundation in St-Paul-de-Vence in August of that year.6 Penrose defended his innocence and continued to pursue the acquisition of the painting, sustained, in the words of art historian Elizabeth Cowling ‘by a quasi-religious conviction in the rightness of his mission’.7

Agreement was finally reached on 29 November 1964. Penrose noted: ‘Things started better – the rain had cleared & a light mistral was clearing the sky – P[icasso] & J[acqueline, Picasso’s wife] were there alone – the dog did not try to bite my bottom as it had yesterday. P. began – saying if we were keen on 3 Dancers he would sell it to us for the £80,000 offered’.8 As soon as the news was received in London, the wheels were set in motion to get the purchase underway, as Picasso was quite capable of changing his mind. Penrose arrived at Picasso’s home in Mougins on 29 January 1965 to finalise the arrangements for transporting the painting to London, accompanied by his wife Lee Miller, who took the famous photograph of Penrose, Picasso, Lee and Jacqueline with the painting in his studio on that occasion.9 Penrose noted: ‘He was very interested in imagining the reactions of the British public and how it would be hung. He did not want it framed with anything more than the baguette it has now. I assured him it would be given a place of honour on a plain background and well lit.’10

It was only when the painting was to leave his studio and travel to London that Picasso finally signed it. Penrose wrote: ‘We agreed that it was in splendid condition, it was only his signature that was lacking. He said he would sign it but had not yet decided just where and how it should be done but historically it was necessary it should be signed. Picasso signed the picture soon afterwards’.11 The signature is in green paint in the lower left corner.

Finally, the painting arrived in London and Penrose revelled in his success. He reported back to Picasso in a letter that Lady Summerskill, a former Labour minister and one of the founders of the UK’s National Health Service, had ‘fulminated furiously’ against the purchase in the House of Lords ‘demanding to know why the government had allowed one or two “idiosyncratic” persons to waste public money on such monstrosities, when hospitals were in dire need of new operating theatres’.12 Penrose was asked to confront her on television and their discussion was listened to by an enormous audience. He wrote to Picasso:

Since then I’ve been inundated with letters that remind me of the good old days when retired colonels came to brandish their umbrellas and spit on modern art. All this was more than counterbalanced by a crowd of very enthusiastic friends. It’s wonderful that your work leaves no one indifferent. Even English phlegm dissipates before your miraculous, southern assault. Any minute now I shall be sending you a photo of the installation in the gallery and I assure you that the attacks of ignoramuses like this poor lady are in no way representative of the general reception of your picture.13

Penrose was delighted by his altercations with Lady Summerskill and that The Three Dancers ‘was as disturbing and provocative in 1965 as it had been in 1925’.14 On the basis that there is no such thing as bad publicity, the passionate vituperation of the painting’s detractors was as gratifying as the adulation of its admirers.

There has always been dispute over the title of the painting. Picasso seems to have referred to it as The Dance (La Danse), while Penrose used the title The Three Dancers (Les Trois Danseuses), which Tate continues to use. However, Picasso disowned this title, revealing later that:

the painting is above all connected to the misery on hearing of the death of an old friend. While I was painting this picture an old friend of mine, Ramon Pichot, died and I have always felt that it should be called The Death of Pichot rather than The Three Dancers. The tall black figure behind the dancer on the right is the presence of Pichot.15

As Picasso scholar Marilyn McCully has discussed, it has also been called The Three Dancers and the Devil and it was first titled in 1925 issue of La Révolution surréaliste as Girls Dancing in Front of a Window (Jeunes Filles Dansant Devant la Fenêtre).16

Pichot died on 1 March 1925. If Picasso’s words above are taken literally this would imply that he had begun the painting before March that year. The timeline of its creation is difficult to establish as it is not known how long he spent working on it, although the date by which it was finished is aided by correspondence with André Breton. Breton had arranged to have the newly completed painting photographed by Man Ray and on 9 June 1925 he sent Picasso a letter apologising for the poor quality of the image.17 In the photograph the figure on the right is visible only in silhouette and the brown face within the black contour can hardly be seen at all. Nevertheless, it appeared in the fourth issue of La Révolution surréaliste on 15 July 1925, along with an image of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted eighteen years before. In the same issue Breton argued that Picasso was a surrealist and proudly claimed him as one of their number.

It is known that Picasso, his wife Olga Khokhlova and their son Paulo left Paris for Monte Carlo on 9 April 1925 and returned in mid-May.18 In 1965 Penrose noted that Picasso said he thought he had painted it in Paris after his return from Monte Carlo in May 1925. Therefore the painting must have been completed in less than a month, judging by the date of Breton’s letter of 9 June. An examination of the upper layers of paint support the idea that it was executed rapidly, and the thick impasto was applied wet-in-wet, picking up and swirling neighbouring colours to create a hectic marbled finish. However, it is not clear as to whether the layers underneath were dry when Picasso revisited the painting in May 1925, nor how long they had been there. The origins of this canvas and its images will be examined in detail in the following section.

As a result of this study it has become clear that the painting was worked on in three separate phases, the uppermost painting completed rapidly between May and June 1925, adding to and completely changing what already existed on the canvas. Beneath the enigmatic upper layer there is a colourful, more figurative image of three dancers, which was examined using X-radiographs and microscopy. This phase relates closely to the small painting called The Dance painted by Picasso in 1923, discussed in detail here. The earliest layer is likely to have been a grisaille painting, possibly connected with a commission from Etienne de Beaumont. This paper will look first at all three stages of the painting and propose a tentative date when work on the canvas was begun.

Stage 1: The beginning of a grisaille composition, autumn 1923

Fig.2

Detail of digital X-radiograph showing tear in the upper-right corner

Photo © Tate

Fig.3

Detail of the same tear under raking light from left

Photo © Tate

The painting arrived at Tate in 1965 on a fixed strainer, which still exists in the Tate conservation archive, albeit disassembled for storage. The first examination was carried out by the then Head of Conservation, Stefan Slabczynsky, in February 1965. In the condition report he described the strainer as original, made of pine, with six members, with no provision made for wedges to make it expandable.19 He noted that the edges of the canvas overlapped the back of the stretcher by 2.5 inches (8 cm) at the top, 2 inches (5 cm) at both sides, and by 1.25 inches (3 cm) at the bottom, and were fixed with staples. The original attachment of the canvas to the strainer was with tacks, including some through the front of the painting into the front face of the strainer, which were then painted over. On the back of the canvas just below the top member of the strainer there is a 38 cm long cut or scratch that penetrated the canvas, which had been noted in the 1973 X-radiograph but became clearer in the most recent X-radiograph (see fig.2). This had been mended with a hessian-type gauze, which was glued onto the reverse of the tear, and remains untouched on the reverse of the painting. It is not recorded how this tear came about and who repaired it. As the painting was still in Picasso’s possession until it came to Tate the repair was presumably done with his knowledge, or he may even have done it himself. The tear is clean cut, almost like a knife cut. It had obviously been disguised on the front of the painting with thickly applied paint applied by the artist (fig.3). Today, cracks radiate out below it as though this linear damage put considerable pressure on the paint surface. The damage at the right end of the tear would suggest that if it was the result of a cut, the knife would have entered at the left and the pressure would have tailed off towards the right end. The horizontal line of the tear is disguised in the upper surface and runs just below the line of the black ceiling. It may have corresponded to the straight edge of the former strainer and an attempt may have been made to cut the canvas to a smaller size, but was soon abandoned.

According to this earlier examination and a later assessment by Tate conservator Roy Perry, the painting was structurally unstable and unable to be loaned abroad without treatment. Perry’s report from 1975 stated that the ‘Edges appear to be in potentially fragile condition with many little splits and holes (from restretching?)’.20 Extended loan abroad was not recommended owing to the age-weakened canvas with worn edges, heavy uneven paint films and a strainer that permitted no adjustments to the canvas tension. Cracking and cleavage had already been treated on previous occasions.21

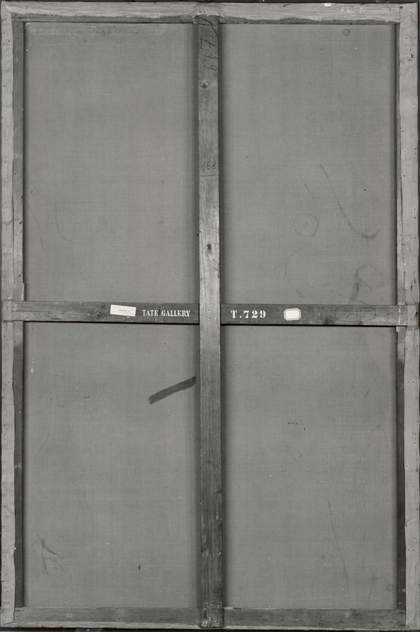

Fig.4

Black and white photograph from 1965 showing the reverse of the canvas and the original strainer

Photo © Tate

A 1965 black and white (B&W) photograph of the reverse shows not only the original strainer: one can discern the outline of the wildly dancing figure on the left (as viewed from the front), seeping through the canvas (fig.4). A shapely feminine leg is visible in the lower corner, which is unlike the final version and therefore comes from the layer beneath. Above the central stretcher bar member, one can also see the neck and base of a rounded head, an outstretched arm, a circular breast and curved lines. It seems that Picasso scored the surface of the painting, and may have followed the lines of some of the existing features, at an early stage. Subsequent painting caused oil to seep through these lines, making these patterns visible on the reverse. On the opposite side of the canvas the outlines of a long neck are visible, which would be consistent with the image beneath the surface.

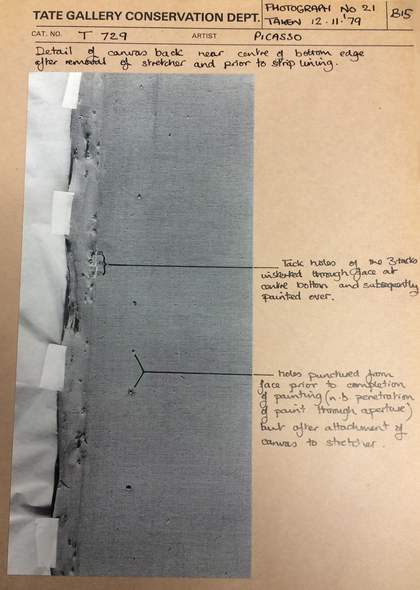

Fig.5

Detail of the reverse in 1979, removed from the strainer and before restretching on a new stretcher, extracted from the conservation record.

Photo © Tate

Fig.6

Detail of the lower edge in 1979 showing triple tack holes in the foldover edge, extracted from the conservation record

Photo © Tate

The groups of three tack-holes along the top edge (fig.5) are very close to the foldover crease. Similar groups of three tack-holes are visible in a black and white photograph of the lower edge of the painting. Unfortunately there is no photograph of the whole of the reverse with the foldover edges pulled back to show whether these tack holes in triplicate are local to these areas, or present all around the edges. The photograph in the conservation report from 1979 (fig.6) also shows holes in the body of the canvas where tacks were driven through the front and painted over, like the three tacks through the front at the bottom edge. It is very unusual for tacks to be applied through the front of a painting, which makes one speculate whether these were residual attachments from a former scheme, with the canvas attached to a flat surface or a temporary strainer from the front. As well as damage at the edges, there are also many losses to the priming, which supports the theory that the edges were handled and restretched, sustaining characteristic wear and damage.

The canvas would appear to have been primed before stretching, as three edges are cut and the priming goes all the way to these cut edges, as is typical for a commercially primed canvas. Only the top edge has a border of bare canvas, but there are no selvedges.22 The canvas is middle weight, with 17 warp threads per centimetre and 18 weft threads per centimetre, a single piece of linen fabric, primed with a grey ground found to contain lead white with bone black in a drying oil, with extensive lead soap aggregate formation from an in situ chemical reaction between the lead white and the oil.23 This was applied to a glue-sized canvas. The size is thick and was likely applied cold.

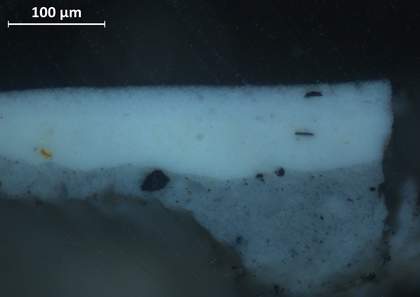

Fig.7a

Detail of right foldover edge, with good colour rendering, showing the grey ground and a dark red brushstroke, which ran onto the side of the stretcher

Photo © Tate

Fig.7b

Micrograph of right edge, with good colour rendering, showing the grey ground to the right and a white paint layer to the left

Photo © Tate

Fig.7c

Detail of reverse at top, with rather poor colour rendering, showing grey ground and cut canvas on foldover edge, with a paler border of added canvas strip lining

Photo © Tate

The grey ground can be seen on all edges (figs.7a–b) and on the reverse foldover (fig.7c). The top reverse foldover edge shows the sort of damage caused by the fabric being gathered and crushed, as would happen if the pre-primed canvas were stretched onto a new support. There also seems to be slight cusping (distortion) in the edges of the fabric, which suggests former stretching, unrelated to this strainer, and interestingly also unrelated to the triple tack holes shown in fig.6, which lie further into the body of the canvas. The edges have been trimmed and there are characteristic losses all around the edges. This begs the questions: if the painting had been in Picasso’s possession all this time, why was it restretched and was it done by Picasso himself? It must have been done with his knowledge, but what was its former function? Sadly, this does not seem to have been discussed with Penrose and remains unanswered.

Fig.8a

Micrograph of the lower border of the breast seen in profile, central figure, showing the grey ground where the black, pink and white colours met wet-in-wet to create a marbled effect

Photo © Tate

Fig.8b

Micrograph of the border of the floor and the panel on the right side, showing the grey priming not fully covered

Photo © Tate

Fig.8c

Micrograph showing the grey ground visible in between brushstrokes for the window casement

Photo © Tate

Fig.8d

Detail showing the grey ground incompletely covered by paint for the yellow floor tiles

Photo © Tate

Fig.9a

Detail showing the diamond shape around the wrists of the clasped hands at the centre of the painting, with grey priming visible

Photo © Tate

Fig.9b

Photomicrograph of the centre of fig.9a, showing the exposed grey ground

Photo © Tate

The grey ground played an important role in the early stages of development of this painting. It appears to have been a conscious choice to leave the grey of the ground exposed at the very centre of the painting (fig.8a) and elsewhere (figs.8b–d). Where the clasped hands meet (figs.9a–b), he left visible a small area of grey ground in the midst of the surrounding impasto. The transmitted light image (fig.10) taken with the canvas lit from behind is somewhat compromised by the fabric of the loose lining behind the painting, but the areas of the painting where the paint is thinnest still glow pink/red. The small area of ground within the clasped hands is very clearly illuminated, as is the exposed ground between the floor and wall panels. Cracks and incised lines in the painting are also rendered brightly.

Fig.10

The Three Dancers 1925 in transmitted light

Photo © Tate

The grey ground possibly played the role of background colour in the first concept, therefore this first painting may have been a composition painted in grisaille. White appears in all losses and cross-sections to be the first layer of paint on top of the grey ground. In the upper-right corner, between the second and third black lines, which can be read as fingers in the raised hand of this figure, the white paint is fragile and has cracked, creating losses down to the canvas threads (fig.11a). It is interesting to note that the paint build-up here is very simple (fig.11b): the grey ground and a layer of white, which seems to have been applied up to and in places over the black at the top. This might be explained by the fact that there are two layers of white (fig.11c), one before the black ‘fingers’ were applied and one after, the latter including some zinc white. There are further splashes of black on top of the white.

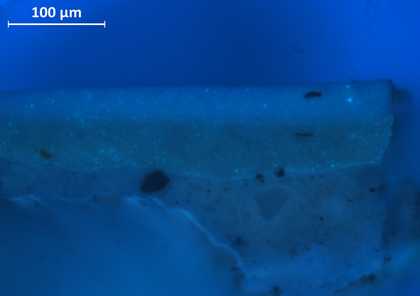

Fig.11a

Micrograph showing losses in the white paint between the second and third fingers

Photo © Tate

Fig.11b

Cross-section of paint taken from loss, viewed under visible light, showing grey ground and white layers on top

Photo © Tate

Fig.11c

Cross-section of paint taken from loss, viewed under ultraviolet light, showing two distinct layers of white, with the bright spots in the upper layer indicating zinc white

Photo © Tate

Fig.12

Detail of breast contour in right figure

Photo © Tate

Visible in a gap in the paint beneath the brown and white paint border, the line of the breast is a simple black line, again on the grey ground with no other adornment (fig.12). It is likely from these glimpses that this figure began as a simple grisaille design; the figure outlined with black contours and the body is then fleshed out with white.

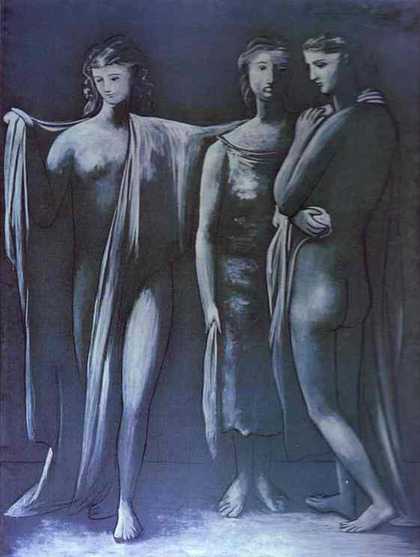

Fig.13

Pablo Picasso

The Three Graces 1923

Oil paint and charcoal on canvas

200 x 150 cm

© Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso. Photograph Marc Domage. All rights reserved.

© Succession Picasso/DACS London 2017

Paintings in grisaille by Picasso from this period include The Three Graces 1923 (fig.13), similar in size to The Three Dancers. Although the figures are very different and were not depicted as nudes, there are possibly similarities in execution. Grisaille paintings are mentioned by Picasso scholar John Richardson in his biography of the artist in connection with Count Étienne de Beaumont, who had asked Picasso to design costumes for The Discovered Statue, a short composition for organ and trumpet by Erik Satie.24 Commissioned as a danced pièce d’occasion, it was originally set to a scenario by Jean Cocteau with choreography by Léonide Massine. It was premiered at a costumed ball held by the Count and Countess de Beaumont in Paris on 30 May 1923.

Picasso had been commissioned to paint four decorative panels on classical subjects for the music room of the de Beaumont’s hôtel particulier. In a letter to the artist on 15 February 1923 de Beaumont wrote:

Here are the measurements for the panels. Would you like me to get the stretchers made? This idea pleases me so much that I would like to see it realised as soon as possible – especially as financially it would be easier for us at the moment thanks to an unexpected windfall.

Would you like to send me your fee for these panels? I would like to say it doesn’t matter how much but alas the buffet is limited … you could see the salon again … if you prefer to make the canvases in situ, nothing simpler than to hand over the room to you for a time – where you would be as if in your own home. You know you have all my affection and admiration – I would like to give you further proof …

Dear friend,

Here are the verified measurements. Nothing could please me more than your idea – I am very excited and I would like to know when you are in possession of the stretchers.

Thank you,

Etienne1. Right hand side (large panel) 2 m 13 cm high x 1 m 78 cm wide

2. Left side (large panel) 2 m 11 1/2 cm x 1 m 78 cm

3. Right side (small panel). 2 m 12 cm high x 1 m 31 1/2 cm wide

4. Left side (small panel). 2 m 12 cm x 1 m 41 1/2 cm wide.25

On 2 March 1923 de Beaumont wrote again: ‘And I look forward to having the panels. Telephone me when I can come and see our projects’.26

The idea that pleased de Beaumont so much is thought to have been Picasso’s vision of grisaille paintings.27 Richardson states that Picasso ‘began with an elegant Three Graces, which the sculptor Apel-les Fenosa recalled seeing in the rue de la Boétie studio in late May’.28 It is not known if this was the painting in fig.13 or whether it could have been the beginnings of another grisaille on this canvas. From this correspondence we can deduce that Picasso chose to work in his studio rather than in situ. However, it seems that this project did not reach completion and Picasso was under pressure from his dealer, Paul Rosenberg, ‘to turn down commissions that entailed a lot of work, little compensation for the artist and no profit whatsoever for the dealer’.29 Nonetheless, the success of the costumed ball and ballet event inspired Étienne de Beaumont to become an impresario like Sergei Diaghilev, who created the Ballets Russes. The following year de Beaumont launched his short-lived Soirées de Paris theatre company and produced several original ballets, the most important of which was the Picasso-Satie-Massine collaboration Mercure in 1924, which seems to have had an important influence on the second phase of The Three Dancers.

In summary, beneath The Three Dancers there is indisputably a grey ground and there would seem to be black outlines, which are only weakly rendered in the X-radiograph (as will be discussed later) but can be glimpsed through gaps in the upper paint. It would also seem from the cut canvas edges with unrelated cusping and perhaps even the oddity of the triplicate tack holes, with tack heads remaining in the surface of the painting, that this canvas was on a different support, possibly even on the wall of Picasso’s studio, and has been restretched, possibly more than once. The canvas may well have been altered in size to fit onto the current strainer. The size of The Three Dancers today (2153 x 1422 mm) is not dissimilar to the grisaille mentioned by Richardson (2000 x 1500 mm) or the dimensions of the panels given by de Beaumont. The Three Dancers might have been conceived as a large grisaille with a more classical rendition of dancing figures. It is different in conception to The Three Graces in fig.13, but perhaps was similar in technique and appearance. It is thus possible that Picasso began painting on this canvas as early as two years before The Three Dancers was finished.

Stage 2: The addition of colour and the relationship between The Three Dancers and The Dance 1923

Fig.14

The Three Dancers 1925 viewed under raking light from the left

Photo © Tate

The second stage of painting is very difficult, if not impossible, to date through technical examination alone. When viewed in raking light (fig.14), the varied texture of the paint is accentuated, and changes to the composition before Picasso arrived at the surface we see today are clear. When looking closely at the textured surface, various pentimenti become visible, such as the contours of more rounded limbs around the legs and feet and a round head above the mask-like face on the left-hand side. The extraordinary texture of the paint is highlighted, as is the uneven paint application from the heavy impasto on the left to the thinner, less heavily worked paint on the right side of the painting.

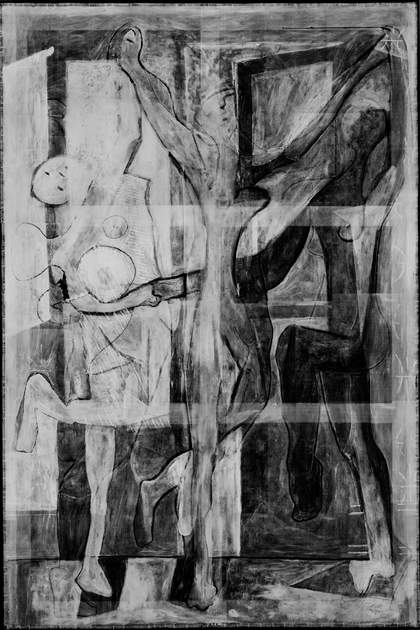

Fig.15a

Film-based partial X-radiograph made in 1973 at the National Gallery, London

Photo © Tate

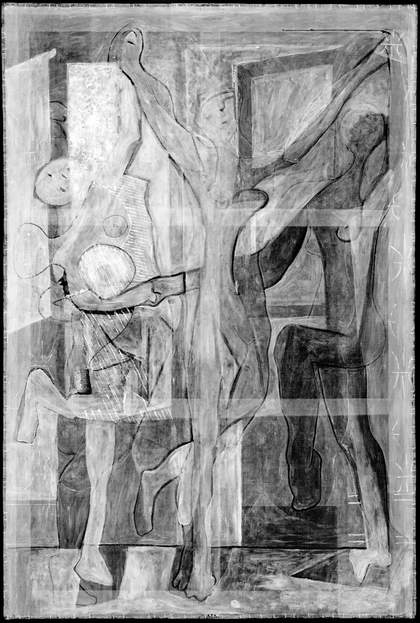

Fig.15b

Film-based X-radiograph made in 2012 at Tate

Photo © Tate

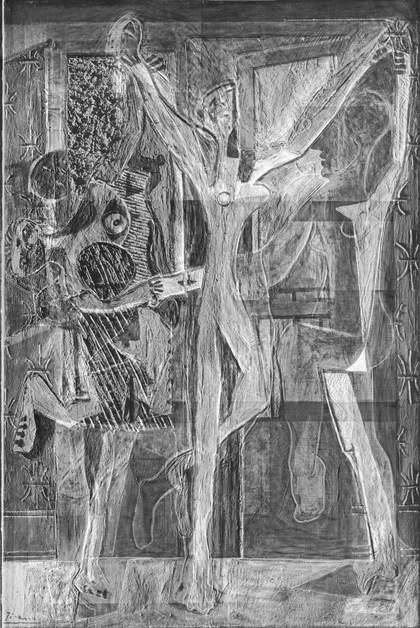

Fig.15c

Digital X-radiograph made in 2015 at Tate

Photo © Tate

In X-radiographs (fig.15a–c) these changes become visible as three dancers of a completely different character. The painting has been X-rayed three times – in 1973, 2012 and 2015 – and each image is slightly different in contrast, but conveys similar information. However, the most recent digital X-radiograph presents the most subtlety.

Fig.16

Short-wave infrared (SWIR) image of The Three Dancers 1925 (1500–1700nm)

Image: John Delaney and Kate Dooley, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The short-wave infrared (SWIR) image in isolation (fig.16) was less helpful in rendering the underlayers than had been hoped, due partly to the thickness of the paint and to the infrared absorption of the pigments in the upper layer. The grey ground also hinders contrast in the infrared image between the black outlines and the substrate.

In order to exploit the full range of information from these images, the black and white areas were inverted to give a white and black positive image, which shows the modelling in the paint more clearly (the thinnest areas of paint then appear white, while the thickest areas of paint appear dark). This was then overlaid with the colour image (fig.17a) in order to localise the area in question relative to the upper surface, and it was also overlaid with the raking light image (fig.17b) to highlight texture and its relation to underlayers. The three figures shown in these images are more rounded, classical nudes in rather stately balletic poses. They have sharp outlines, probably in black paint, and have been ‘fleshed out’ with thinly applied paint. The figure on the right is the most clearly defined by this means, because the paint applied over it is thinnest, whereas the figure on the left has received a much heavier secondary application of paint, which largely obscures its underlayers.

Fig.17a

White and black image from the 2012 X-radiograph layered with the coloured, visible light image

Photo © Tate

Image: Rod Tidnam

Fig.17b

White and black image from the 2012 X-radiograph layered with the raking light image from left

Photo © Tate

Image: Rod Tidnam

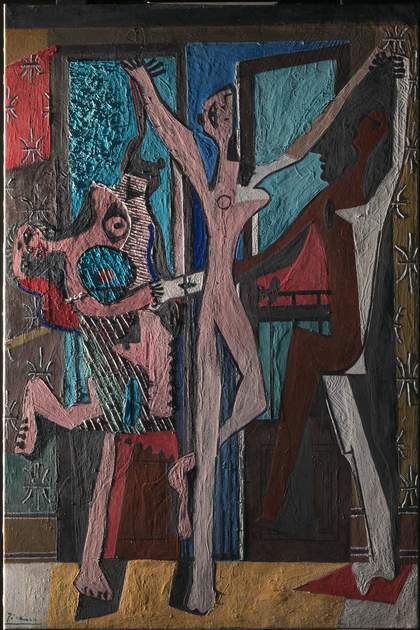

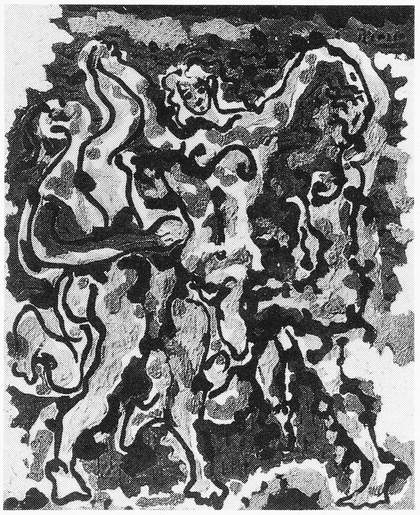

Fig.18

Pablo Picasso

The Dance 1923

Oil paint on canvas

27 x 22 cm

© Succession Picasso/DACS London 2017

Photograph originally published in Christian Zervos, Pablo Picasso: Catalogue of Works, 1895–1972, 33 vols, Paris 1932, vol.5, no.148.

The painting above was compared by Tate curator Ronald Alley to a small oil sketch called The Dance 1923, now lost but published in the catalogue raisonné by Zervos and in Alley’s book on The Three Dancers (fig.18).30 This illustration provides an invaluable guide to what may have existed as the second image on the canvas, before the final image was created in June 1925.

Close comparison of The Dance and the inverted X-radiograph overlaid with colour (fig.17a) yield some interesting similarities, particularly in the lowest section of the painting, which had been missing from the 1973 X-radiograph. The feet of the dancers are a study of three different positions from three different vantage points, depicted as (from left figure to right figure), tip-toe from behind, tip-toe from the front and tip-toe viewed from the side. The details of weight-bearing feet from The Dance, are remarkably similar to those of The Three Dancers. They are not dissimilar in execution either: the feet in The Dance seem mainly defined by thick black outlines and are less finished, while those in The Three Dancers are more neatly rendered and seem to have some modelling within their outlines. Each figure was examined in detail to test whether the similarities extend to the rest of the painting.

The left figure

The dancer on the left is the one which underwent the most dramatic changes in the revision of the painting in 1925. The line of the shapely leg up to the buttock and the arched back also bear a close resemblance to The Dance. The round head in The Dance seems to be looking back over her shoulder to confront the viewer and one can see only the profile of her right breast. Picasso incised the line of the back of the first figure and the outline of the breast in profile, so they are accentuated in the X-radiograph and are rendered as white outlines in fig.17a. They consequently also appear in profile on the reverse of the canvas, as noted earlier. He also incised a circular breast in this figure, which appears on the reverse, but this would appear to belong to the later painting, The Three Dancers. Picasso painted over it with pink and thick black outlines, reassembling an extra sightless eye. The figure beneath also appears to be a nude of simple outline and voluptuous limbs, but this is difficult to verify fully because the paint in the upper layers is so thick as to conceal large areas. There is a very long and impossibly curved left arm extending to meet the hand of the central figure, which was revised and shortened in the later version. Above the head, there are unexplained and unresolved black outlines in the X-radiograph, which recede beneath the thick paint of the surface and cannot be ‘read’. The round head, thrown back and staring out above the existing head, has a simply painted face, with eyes, nose and mouth little more than black dots and dashes. This contrasts with the features of the face in The Dance, which although hard to decipher definitively, resemble a monstrous mask in contrast to the other two, which appear to be depicted as more conventionally attractive and feminine. In The Dance Picasso seemed to be playing with the idea of a dancer’s body with a mask-like face, which does not appear in what can be seen of this first version of The Three Dancers, but he returned to it with alacrity when The Three Dancers burst into existence in mid-1925.

The central figure

The central figure of The Three Dancers can equally be teased out by comparing with the middle dancer in The Dance. This figure in The Dance, also nude, stands on one foot facing the viewer almost head on. She has a halo of long flowing hair framing her pretty round face and has a timid expression, abbreviated to a few dots. In the white and black X-radiograph of The Three Dancers there at first seems to be no similarity with the head of this figure. However, a very faint outline, unidentifiable on its own, begins to take the shape of the head of the central dancer in The Dance when they are viewed together. Note the wavy line at the left of the head, the circular shape above the head, the window frame, the ear and the line of the neck to the right of the head, and even the possibility of eyes and a mouth within the face. The horizontal S-shaped breast formation of The Dance is also echoed in The Three Dancers. The torso of the central figure emerges when compared to the example of The Dance. The body is facing the viewer almost square on and the outline of the hips, the crease of the unaccentuated sex and even a belly button becomes clear. In The Three Dancers the figure has been twisted to the side, showing one breast in profile, and the figure has an impossibly waspish waist.

The right figure

Fig.19

Detail from black and white photograph taken in 1979 of The Three Dancers under raking light from below, showing multiple heads for the right-hand figure

Photo © Tate

Despite obvious deviations in the style of the two paintings, there are some resonances in the design of the right figure. The feet and legs are in similar positions, while both have rounded haunches. The breasts are in roughly the same position and the right breast has the same curled line which defines it. The most interesting part is the head. In The Dance it is the black linear outline of a beautiful classical profile, quite hard to see as it does not follow the white impasto area of paint within it. Strands of black hair are delineated flowing out behind the head. In The Three Dancers, one can at first see three different heads: the large black shadowy figure in profile, a round, ball-like head and a smaller rounded head in profile within it. However, on close inspection there is a very faint profile of a classical face similar to that in The Dance, and there are some unexplained wavy lines above the head, which could represent flowing hair. This classical profile with flowing wavy hair resembles many of Picasso’s drawings of classical heads from 1923. That this face is barely detectable in the X-radiograph suggests it is either painted very thinly or in pigments which are largely transparent to X-rays – perhaps mainly in a carbon-based black such as lamp black. This makes it very difficult to see at first, and without the clue of the head in The Dance it might not be discernible at all. However, it can be detected in raking light (fig.19). This suggests that the figure began life as a simple profile, possibly a black line on the grey ground, which would support the idea of a grisaille.

Fig.20

Photograph of costumes and set by Picasso for ballet Mercure, 1924

© Succession Picasso/DACS London 2017

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso, Paris)

Fig.21

Pablo Picasso

Study for Mercure 1924

Graphite on paper

27 x 21 cm

© Succession Picasso/DACS London 2017

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso, Paris)

The ballet Mercure may provide a crucial link between 1923 and 1925.31 The ballet consisted of three scenes of dancers in poses plastiques in front of scenery designed by Picasso. The scenes appear to have consisted of solid black outlines, possibly made of wire, propped at some distance from areas of colour on a backcloth, and casting shadows (fig.20). The pencil drawing in fig.21 is not dissimilar to the shapes and lines formed in the small 1923 painting The Dance. Picasso seems to have drawn the figures in a few continuous sweeps of the pencil. The wavy lines for the hair and the S-shaped outline of the breasts are similar to the earlier design. Paintings made as studies for Mercure feature similar dark contours and islands of what looks like impasto colour which do not correspond closely to the outlines but provide a lively background for the figures.

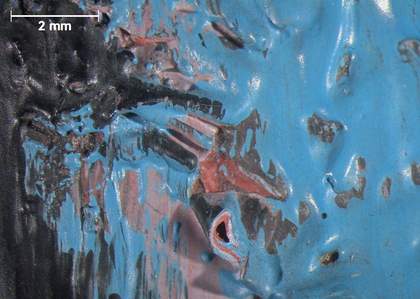

Fig.22a

Detail of loss at top left corner

Photo © Tate

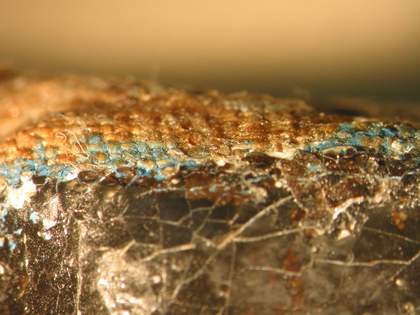

Fig.22b

Micrograph of incised line around head of left figure, showing blue paint in underlying layers

Photo © Tate

Fig.22c

Micrograph of upper left corner of the window on the right, showing three types of blue: one in the underlayer and two on top

Photo © Tate

The Dance 1923 was photographed only in black and white. However, beneath the final painting of The Three Dancers there are areas of colour, some vibrant, unrelated to that image and lying on top of the grey background, possibly providing islands of colour around the figures as is presumed to be the case for The Dance. A study of the surface using a light microscope is helpful to determine which layers might belong to which campaign of painting. There is a dried blue layer of paint beneath the top painting and this appears around the edges, in gaps in the paint and in incisions throughout the painting (figs.22a–b). This would seem to relate to an interim background colour, distinct from the two types of blue used in The Three Dancers (fig.22c).

In addition to the blue there are many other colours visible between the surface cracks. Penrose noted in his conversations with Picasso that the artist was aware of and liked the drying cracks that had appeared in The Three Dancers:

I examined closely the cracks in the painting on the left side, specially round the head of the dancer. Noticing my interest P. said, ‘The paint is solid enough and will not flake off. Some people might want to touch them out but I think they add to the painting. On the face you see how they reveal the eye that was painted underneath’. I said I thought it much better to leave them as they are, and he agreed emphatically. We agreed that the painting was in splendid condition.32

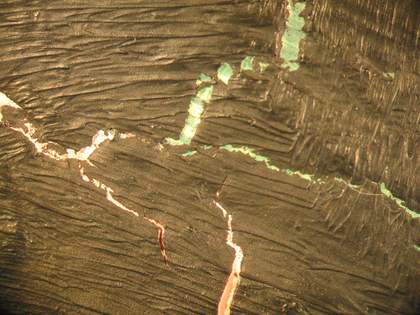

These drying cracks do indeed provide information about the composition of the under layers of the painting before Picasso completely changed it. The black areas seem to have been added at the end of painting and define large areas of the composition, not least the brooding presence in the right-hand side of the painting. Picasso also seems to have struggled with the final form of the left figure, changing the length of the curved arm and the shape of the head. These seem to have been resolved by creating the black shadows around her head. Black oil paint is notoriously slow to dry and on top of layers of dry paint, it would have formed a skin on the surface while the body of the paint remained soft. As the lower portion of the paint film dried, the tight top skin would have contracted and caused these tears or drying cracks in the paint.

Fig.23a

Detail from the left figure, showing green marbled with yellow paint in the layer beneath the black

Photo © Tate

Fig.23b

Detail near fig.23a, showing where pink paint meets earlier green paint

Photo © Tate

Fig.23c

Raised arm of the left figure, showing earlier pink and red paint

Photo © Tate

Fig.23d

Detail from 2012 X-radiograph showing same area as fig.23c

Photo © Tate

There is green mingled with yellow bordering an area of pink in the section beneath the bulbous black silhouette of the left figure (figs.23a–c). From the 2012 black and white X-radiograph of this area (fig.23d) we can see that the pink probably belonged to the former arm of the figure underneath, but there is not much visual information providing clues about the background. Similarly in the other areas around this figure there are incongruous colours beneath the drying cracks in the upper layer. Details at the face of the left figure (figs.24a–b) show the expected pink and white for an earlier realistic face, but there are also traces of brown, blue, black and yellow, although the area of brown wallpaper does not seem to be the same as the brown of the surface. A close-up detail of the eye in the shadowy figure on the right (figs.25a–b) reveals that it was created by subtraction rather than the addition of paint, with brown over white visible beneath the pink of a possible earlier face.

Fig.24a

Micrograph of area between red and blue planes showing brown, yellow and blue paint beneath

Photo © Tate

Fig.24b

Micrograph of the area around the mask-like face of the left figure, below the mouth in the black area, showing pink, brown and black paint beneath

Photo © Tate

Figs.25a–b

The dark head on the right and micrograph showing the eye

Photo © Tate

Not much information could be obtained about the shapes and colours of the background to the earlier painting with the examination methods available, but the complexity of layers and colours which lie underneath is obvious. It would seem from the underlying colours that the scene was not enclosed in an interior space initially and may have resembled more closely the slightly abstract plein air scene of The Dance 1923.

Stage 3: Work before March 1925, after May 1925, and until completion in June

The final form of the painting has given rise to much speculation among scholars as to when it was painted and what it might mean. As mentioned above, the black figure at the right of the painting has been said to be the profile of Pichot. Picasso scholar Marilyn McCully argues that as well as being inspired by the tragic death of his friend, Picasso may have been influenced by the poses struck by the ballet dancers seen during his visit to Monte Carlo as well as the ballet Zephire et Flore in 1925, citing a particularly striking photograph of Serge Lifar and Alice Nikitina dancing in that same ballet.33 Their poses could have been the inspiration for the figures at the right and left of The Three Dancers. McCully writes:

Another way of interpreting the role of the male figure in The Three Dancers is that Picasso was actually inspired by something he had seen in the ballet. If this is the case, the male figure could simply be a dancer rather than a spectre of death or the devil in the scene. When Roland Penrose discussed the painting with Picasso in 1965, Penrose noted that the composition had ‘nothing to do with the ballet’. However, this does not take into account the genesis of the painting, in which the first stage clearly reveals that the poses of the three dancers are inspired by the ballet … This suggestion is made not to deny that Picasso was thinking about Pichot when he added the male profile, but to raise the possibility that there was a more direct source of inspiration in the ballet that he saw in Monte Carlo, before the reworking of the canvas on his return to his Paris studio.34

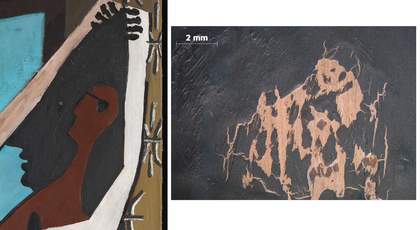

Fig.26

Detail of the left figure

Photo © Tate

The most dramatic changes in the painting were made to the left figure of The Three Dancers. Nikitina dancing Zephire et Flore does indeed have similarities to the pose of the dancer on the left, but from the rather benign, attractive nude figure suggested in the X-radiographs, subject to the admiring male gaze, she turned into a hideous and threatening maenadic figure with widely spaced teeth between vampish red lips (fig.26). The face looks like a skull, with dark hollows for eyes and a nose, just one eye illuminated by a demonic white light from within. The mouth looks like a vagina dentata, which is echoed by the jagged shapes further down her body. The teeth are widely spaced and ugly and the red lips repellant and dangerous. There is also a strange shape on her forehead, which looks like a distorted crescent moon. Picasso obviously played with the outlines of this head as there is pink beneath the black showing through the drying cracks, and the neckline and outline of the head was reduced with additional black paint, cinching it in at the neck and removing half of her oval face.

Fig.27

Examples of Ekoi masks

© Trustees of the British Museum

This face has often been associated with African masks, and it has been suggested that it most resembles a mask from the Ekoi-speaking people from the Cross River State of the Nigeria and Cameroon borders (figs.27a–b).35 These masks were made of wood and then coated with skin, formerly the human skin of slaves, but latterly of antelopes, stretched over the wooden base and stained with colours made from leaves and bark. The eyes were made of metal with solid wooden dark eyeballs, and metal teeth were inserted into the open jaws.

Art historian Elizabeth Cowling writes of Picasso’s imagery in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907 that he ‘did not imitate masks from any particular tribe, however, for he did not want to play the ethnographer but to create an aura of “savagery”’.36 This insight is also applicable to The Three Dancers, where the monstrous face of the dancer on the left is placed on a very modern-looking body with the bright red lips of a very Western femme fatale. Picasso’s use of African masks is not literal, but it is perhaps relevant to his fears and superstitions. A description of Picasso’s first encounter with African art was afforded by his partner Françoise Gilot in her memoirs. In 1946 Picasso is reported to have said:

When I went for the first time, at Derain’s urging, to the Trocadero museum the smell of dampness and rot there stuck in my throat. It depressed me so much I wanted to get out fast, but I stayed and studied. Men had made those masks and other objects for a sacred purpose, a magic purpose, as a kind of mediation between themselves and the unknown hostile forces that surrounded them, in order to overcome their fear and horror by giving it a form and an image. At the moment I realized that this was what painting was all about. Painting isn’t an aesthetic operation; it’s a form of magic designed as a mediator between this strange, hostile world and us, a way of seizing power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires. When I came to that realization, I knew I had found my way.37

Picasso described Les Demoiselles d’Avignon as his first ‘exorcising’ painting. Perhaps he reverted to this form of exorcism in The Three Dancers as a way of dealing with the death of his friend.

The painting materials

Fig.28

The Three Dancers 1925 in ultraviolet light (UV)

Photo © Tate

Just as the meaning of the final version of this painting is difficult to grasp, it is extremely difficult to ascertain the layer structure from surface examination. One of the aims of this study was to look at cross-sections through the paint, to examine not only the order of paint application throughout the whole depth of the painting but also to see whether the time between paint applications could be estimated by the degree of drying between paint applications.

Picasso seems to have used at least two different blues in this final stage of painting, possibly three, as can be seen in the ultraviolet (UV) image (fig.28) and by close examination (fig.22c). Prussian blue and ultramarine mixed with white (which is a warmer, more purple-hued blue), were identified. The UV image shows that the blue of what is presumably open sky between the windows differs from the blue of the windows themselves. It also renders visible some zinc white-based paint which fluoresces with a slightly green tinge in the right-hand figure, the chemise and stripy skirt of the left figure, and the details of the wallpaper. Significantly, the ready recognition of so many different fluorescent materials in the UV image implies there is no overall varnish on the painting, which was borne out by surface examination. The play of matte and gloss paint is important in this painting and was exploited to the full by Picasso.

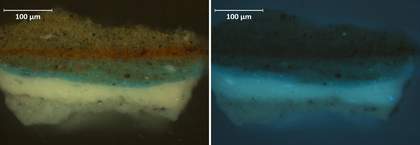

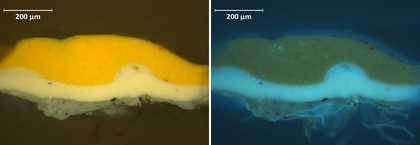

Figs.29a–b

Cross-section showing grey ground, white then blue under browns of window embrasure, in visible light and ultraviolet light

Cross-section made by Fotini Koussiaki

Image: Joyce H. Townsend

Photo © Tate

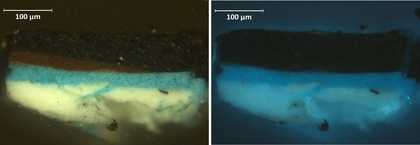

Figs.29c–d

Cross-section showing white, blue flowing into cracks, brown of window and black of ceiling, in visible light and ultraviolet light. The grey ground is missing from this sample.

Cross-section made by Fotini Koussiaki

Image: Joyce H. Townsend

Photo © Tate

Blue plays an important role in the painting immediately beneath the final version. The first colour applied to the grey ground discernible in the cross-sections is lead white (figs.29a–d). There are small glimpses of black outlines applied directly to the grey ground, as mentioned earlier in the examination of the right-hand figure. These are both commensurate with the idea of a grisaille painting as the first campaign. The grey ground and the white paint are both discrete layers which seem to have dried thoroughly before the blue was applied. The blue paint shown in fig.29d even flowed into an existing crack in the white paint. This sample was taken from the area around the tear and the concomitant radiating cracks, which would explain why a relatively young paint film was already cracked ‒ and implies the tear or cut was made to the grisaille image.

The blue layer here was possibly still soft when the final layers were applied. In fig.29a in particular, the blue still seems to have been soft when the brown was applied over it, and there is some mingling of the colours at the border of paint layers. This suggests that the final brown layers were applied not long after these areas of blue. One hypothesis is that Picasso had begun adding colour to an outdoor scene in early 1925, when the death of Pichot prompted him to change direction completely and enclose the scene in a claustrophobic interior, also changing the dancers into the gruesome figures they are today. The blue paint is a mixture of lead white with some zinc white, and Prussian blue, and the browns are a mixture of Mars yellow and Mars orange, which are both brightly coloured synthetic versions of the traditional earth pigments based on iron oxides.

If Picasso returned to the painting immediately upon his return from Monte Carlo, this might explain the softness of the underlying blue paint when the upper layers were applied. The blue does not seem to have been fresh, as there is no mingling of the colour in the surface of the painting, but it was also not completely dried, in contrast to the grey and the white layers. A gap of a month or so could be reflected in the partial drying of the area of blue sampled, after which a skin on the surface of the paint could still be disturbed by the vigorous working of a brush.

Fig.30a

Detail showing the impasto with broken tips

Image: Annette King

Photo © Tate

Fig.30b

Micrograph showing multi-coloured paint beneath the blue

Image: Annette King

Photo © Tate

The most intriguing area of underlying colour is in the textured blue of the left window. Here Picasso seems to have very deliberately laid in multi-coloured paint with a lumpy texture within the window frame. This texture on the left of the painting is perhaps designed to imitate the flash of the sun on glass. Picasso used multi-coloured lumps of semi-dried paint which have held their form and have not mixed with the upper blue paint, but formed a broken impasto peak folded over on itself, with layers within of pink, white and black (fig.30a). The extraordinary stripy detail (fig.30b) above peeks out from the unctuous blue layer brushed thickly over it. Could these lumps be palette scrapings, semi-dried and applied with a spatula, or just swirls of paint, applied thickly with some sort of drying agent to make them dry quickly before receiving the upper blue? The upper blue has been brushed on, retaining the directional brushmarks and skipping the valleys of the textured underlayer. In the brushmarks of the surface, the blue has separated slightly, showing a darker and lighter blue combined. Analysis indicates that the upper blue consists of lead white and Prussian blue. The multi-coloured paint beneath could not be sampled and so has not been analysed, since it would be difficult to isolate the separate colours.

Fig.31

Micrograph showing paint loss in the straight leg of the left figure, showing a layer structure including pink flesh colour

Image: Annette King

Photo © Tate

A small loss in the flesh of the straight leg of the left figure (fig.31) is revealing, as it shows the layer structure of the paint right down to the canvas. The grey ground of the very lowest layer can be seen, and this is covered with white. There is then what appears to be a black layer, covered with a dark pink before the upper paler pink is applied. This represents the three separate campaigns of painting, from grisaille to the flesh of the first figure and finally the pink of the upper surface. Samples from the central figure included lead white, chalk, barytes, magnesium carbonate and drying oil, a combination which suggests the use of Winsor & Newton paints, a highly-regarded British supplier whose exported paints would have been readily available in Paris. The pink pigment could not be identified.

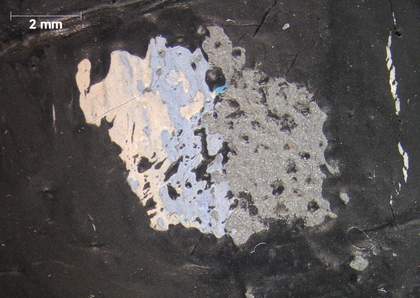

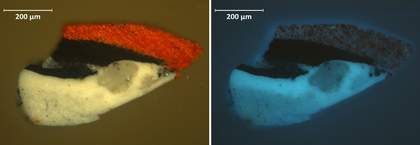

Figs.32a–b

Cross-section from yellow floor tiles, showing canvas threads with glue size, grey ground, white layer, different white/pale grey and yellow as top layer, in visible light and ultraviolet light

Cross-section made by Fotini Koussiaki

Image: Joyce H. Townsend

Photo © Tate

Figs.33a–b

Cross-section from red area beneath the head of the left figure, showing grey ground, white with lead soap aggregates, black, white, black and red, in visible light and ultraviolet light

Cross-section made by Fotini Koussiaki

Image: Joyce H. Townsend

Photo © Tate

The pigments identified in the yellow floor tiles (figs.32a–b) were found to include lead white, chalk and zinc white. The yellow pigment was not fully identified, yet Indian yellow is suggested in the ultraviolet cross-section. This is a light-sensitive pigment rarely used by this date, and the area is quite a low-key yellow today. The sample taken from the area beneath the head of the left figure (figs.33a–b) consists of the grey ground, lead white, bone black, a lead white pentimento then further bone black and finally vermilion red. The recent analytical results for these samples suggest artists’ oil tube paint. A sample of white paint on the surface taken in 1982 (location of sample not recorded) was found to be in poppy oil, therefore it is most probably an artists’ tube colour.38

Fig.34

Detail showing dark blue paint of line beneath red area, and mint green of stripes in skirt

Photo © Tate

Fig.35

Signature at lower left corner added by Picasso in 1964

Photo © Tate

There is no analytical evidence that suggests Picasso employed house paints for The Three Dancers, nor any indicators from the cross-sections that he used anything other than artists’ tube paints for the earlier compositions. A glossy dark blue, a stripe of which is located under the head of the left figure (fig.34), is possibly the only candidate for an identifiable Ripolin house paint called Bleu Outremer 13.

The paint of the green signature (fig.35) applied in 1964 consists of zinc yellow, Prussian blue and barium sulphate, possibly with some zinc white, which also suggests artists’ quality tube paint.

Conclusion

This examination has led to many new insights into the development of this complex painting. There is evidence that this canvas was begun as a grisaille painting, at a similar time as the abandoned grisaille paintings which were intended to adorn the de Beaumont Music Room in autumn 1923. The ground is grey and the first layers were white and black, which had both dried thoroughly before colourful paint was added. The grisaille painting may have been attached to a different support, possibly a wall or a larger strainer, and the canvas was cut down in size for subsequent images. The cut to the upper edge of the canvas occurred to the painting at an early stage, and represents an early, abandoned attempt to remove the grisaille from its initial support.

The small lost painting, The Dance 1923, is thought to have been executed in autumn 1923. This composition was possibly inspired by Picasso’s earlier ideas for the de Beaumont panels in grisaille. Picasso is not known to have made sketches, but the poses of the figures in The Dance are very similar to those revealed by X-radiography beneath The Three Dancers. It is possible that Picasso worked out the figures in a large grisaille before he painted The Dance as a further exploration of the theme, or that inspiration for the larger painting was taken from this small, freely executed painting. There is no indication that the earliest figures now forming the underlayers of The Three Dancers were radically different in position from those discernible in the X-radiographs. Picasso then painted a large scene of three rather classical nude dancers, depicted in quite a three-dimensional manner: their flesh was a greyish dark pink colour, assuming the visible colour at one small loss in the flesh of the left figure was consistent across all the figures. There are numerous colours in the background which can be seen through the drying cracks in the upper painting, possibly forming an abstract plein air setting for the dancers. Further colours were added on top of the lower blue while it was still soft such as the brown layers of the architectural setting. It is known that Pichot died on 1 March 1925, the event avowed by Picasso to be the stimulus for the dramatic changes to the painting. He was in Monte Carlo from 9 April until mid-May when he returned to Paris. The Three Dancers was finished by early June. From the new findings in this study, our conclusion is that the painting was worked on by the artist before his trip to Monte Carlo, and then again upon his return, into still-drying paint, completely changing the different aspects of the composition in dramatic and inexplicable ways.

Picasso’s manipulation of texture, gloss and colour, and the speed of execution for the upper painting, are remarkable. He was also at pains to leave exposed tiny areas of the grey ground beneath, perhaps reminiscent (to him at least) of its beginnings. He seems to have liked the way the paint aged, celebrating the way the drying cracks exposed what lay beneath.

Picasso juxtaposed the looming, black shadowy figure, blending it into dark straight architectural lines, which seem to suck light out of the painting to create a lowering, imprisoning space, while bright unmodified blues of various hues flood the picture with dazzling glare. The writer Georges Bataille described the effect of this painting as ‘horror emanating from a brilliant arc lamp’, or the ‘blinding, maddening sight of the actual noonday sun’.39 The smooth surfaces and decorative wallpaper of a harmless interior are undermined by jarring colours, jagged impasto and mysterious multi-coloured lumps of textured paint. The whole painting is on edge, the window opening inwards and entering the viewer’s space, while all the figures are teetering on tip-toe on one foot, about to come tumbling out of the confined interior.

From the evolution of The Three Dancers, it seems that it was only when moved by extraordinary events that Picasso was finally able to overcome indecision and create something entirely out of the ordinary. That the artist worked on this canvas in three different painting campaigns and that it represented an emotional struggle for him, may go some way to explaining why he was so loath to part with it, even decades later.