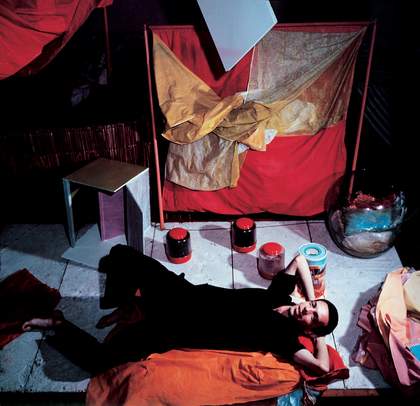

Hélio Oiticica near The Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1969

© Projeto Hélio Oiticica

I arrived in London in October 1969 and lived there until January 1972. It’s true that the display of a work of Hélio Oiticica’s at one of our concerts was a factor in our harassment by the military dictatorship, which eventually forced us to leave Brazil. That particular work consisted of a flag showing a picture of a notorious outlaw from Rio lying on the ground, shot dead by the police, and the words “Seja marginal, seja herói” (“Be an outlaw, be a hero”). Gilberto Gil, Os Mutantes and I displayed it on stage. Left-wing artists, students and journalists would boo us for being too receptive to rock sounds, while right-wing supporters of the government wouldn’t accept popular musicians who presented their songs underlined by such provocative visual elements. One evening somebody in the audience – we heard it was an attorney or a judge – left the night club where we were playing, assuring whoever could hear him that we were going to be punished. A few days later the club was forbidden from opening its doors. Eventually, we were put in jail: the authorities had heard we had disrespected the Brazilian flag. The word flag reached our inquisitors’ ears in a distorted story, but the fact is that Hélio’s rebellious attitude echoed in everything we did.

The first thing I remember about London was getting on a red bus (on my first day in town) with Hélio and his friends Jill Drower and Josephine Rankin, two beautiful, stylish and very British girls. Of course, I wanted to sit on the upper deck – and found it wonderful to see the streets from that height and be able to smoke up there. A few days later I was amazed to find out that one could also smoke in movie houses and theatres. Hélio always seemed to be above those little anthropological discoveries I was making. He was very impatient. Still, he was the one who made everything feel lively.

I saw him almost every day while he was in London. I heard about Hélio’s exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery from other people: Jill, Paul Keeler, Edward Pope. But Hélio himself talked about things he was beginning to think about, and very little about those he had done. I knew his work was very bold, and considered it important that London art people and critics should get to know it.

In 1967 I had composed a song whose lyric sounded like a strange portrait of Brazil. It was already recorded, but had no title. The film photographer and producer Luiz Carlos Barreto – who was the cinematographer for Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Vidas Secas and Glauber Rocha’s Terra em Transe – heard me singing it at a mutual acquaintance’s house in São Paulo, with just my guitar, and immediately told me I should name it Tropicália. He said it felt exactly like the environmental work he had just seen in Rio by this young artist named Oiticica. I didn’t want to use someone else’s work’s title: the artist might not like my song. Besides, being “tropical” didn’t seem to me the most relevant of the aspects of Brazil I wanted to depict.

But the title stuck to the song. And when Hélio heard it, he liked the whole story – he already knew what I had been doing, and approved of it. Admiring Godard and The Beatles, I belonged to a group of Bahian musicians who wanted to refer to rock’n’roll, Hollywood, raw samba from the favelas (shanty towns), crude north-eastern rural flutes, Argentinian tangos, Mexican boleros and Brazilian low-level commercial music. Such a mixture took us near to what was beginning to be known as counter-culture. To us it also meant a more effective response to the violent situation of living under a military dictatorship. Hélio’s experimentation in art, although not romantic in its origins (he came from a Constructivist, Mondrianesque tradition of radical confrontation of visual forms), led him to sympathise with our movement.

I originally met him through a mutual friend, the journalist Marisa Alvarez Lima. I found him wildly intelligent and very funny. I could see he was also very rigorous when it came to his work and his artistic ideas. We immediately became friends. In fact, more than friends: companions on a mission. I soon understood he was the most inventive follower of Lygia Clark. She and he were the two most important creators of the so-called Neo-Concrete group, a continuation of and opposition to the São Paulo Concrete movement. Their beyond-geometry experiments eventually led them to environmental art, clothes and therapy.When he made Tropicália, he had just touched the Pop area of art creation, without making Pop Art at all. The very presence of a television set at the end of a labyrinth punctuated with tropical stereotypes (but also made of very real tropical materials – organic and inorganic – that could be touched) encapsulated our ironic view of, criticism of, blind love for and freedom from the subject matter in Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup paintings and Lichtenstein’s comic-book scenes. So it seemed perfectly natural that Oiticica liked our TV appearances, our interviews, statements and clothes. His Parangolés, transcendental robes and coats, were the most sublime anti-fashion clothes design: quasi-impossible to wear, they at first seemed to be nothing, then you would try them on and, in the process, you’d discover multiple meanings. You’d get over-excited with myriad suggestions: they produced thoughts, feelings, inspirations. Hélio liked to ask young guys from Mangueira – the Rio favela in which the greatest number of geniuses of samba dancing, singing and songwriting lived – to wear them. He also used to say that Mangueira people inspired him to invent the Parangolés – just as the narrow alleys between the houses in the favela inspired him to create the Tropicália labyrinth. Still, he was as opposed to the nationalistic defence of our popular culture as I was. And I loved Mangueira samba people as much as he did.

Now I miss his demanding, almost intolerant critical views, his enthusiasm, his crude sense of humour. He left us a treasure of colours and ideas. We are stronger because of his audacity. Before he died he seemed to be not only less interested in my musical work, but also a bit impatient with what might have appeared to him as a lazy attitude on my part. I understood none of us could feel love at first sight again and again. But I took his demanding view seriously and kept on trying to live up to it.