Two bodies of work by Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980) first brought this multi-talented Brazilian artist to my attention: his Bólides and Parangolés, both from the late 1960s. The first are small three-dimensional pieces, often handmade painted boxes, that include brightly coloured pigment and other elemental materials. The latter were a kind of life-art that came out of a time when Oiticica went to live with inhabitants of the Mangueira favela, or shanty town, in Rio de Janeiro, creating personalised versions of carnival dance rituals and costumes to go with them. Both related to other artists’ work of that time, but also retained a personal and very Brazilian flavour. The titles themselves are particular: bólide means fireball, while parangolé is a hard-to-define word in Rio slang for the devious behaviour associated with the malandro figure – a well-dressed ne’er-do-well who lives off women, his style and wits. Oiticica wrote extensively about his artistic theories and strategies, and created or appropriated emotive terms for his work. One that he invented – Tropicália – became an elastic keyword for a group of musicians he knew, Caetano Veloso and Torquato Neto among them.

Hélio Oiticica

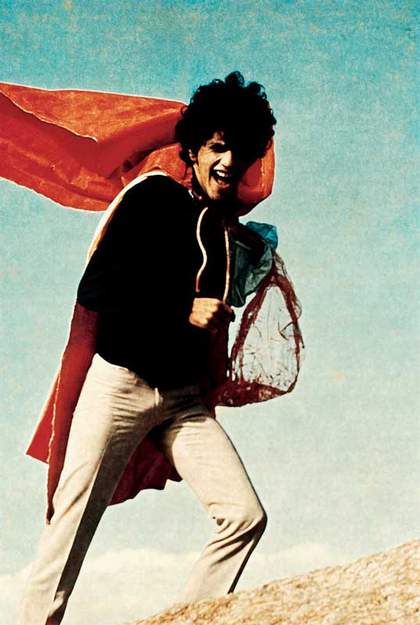

P 04 Parangolé Cape 01 1964

Singer and composer Caetano Veloso wearing the cape in 1968

Photo: Andreas Valentim © Projeto Hélio Oiticica

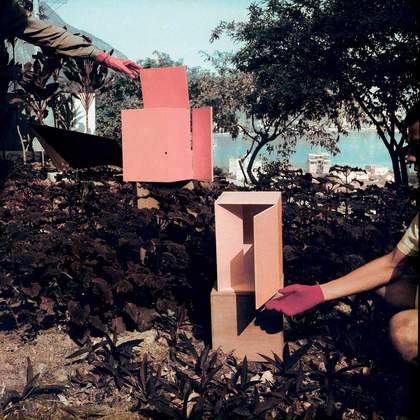

Hélio Oiticica

B1 Box Bólide 1 Cartesiano 1963 and B2 Box Bólide 2 Platónico 1963

Photo: Claudio Oiticica © Projeto Hélio Oiticica

While not a household name, Oiticica has, over the past ten years or so, gained recognition as a premier artist of Brazil’s late Modernist phase. Like many of his contemporaries in the country’s avant-garde, he made work that, by its nature, would not be accepted by mainstream institutions. Since his death in 1980 he has had solo gallery shows and been included in important group exhibitions. Now a major museum exhibition, Hélio Oiticica: The Body of Colour, organised by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is coming to Tate Modern, providing an unparalleled opportunity to examine the production of this mercurial artist during the crucial years in which he transformed himself from the precocious Neo-Constructivist acolyte of the 1950s into the revolutionary barrier-smasher of the 1960s. His later work, partially done in New York during the 1970s, will be the subject of a future Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, show.

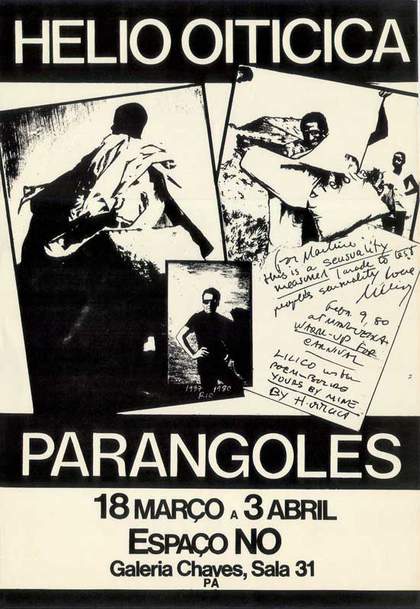

Poster for Oiticica’s exhibition of Parangolés at the Galeria Chaves, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1972

© Projeto Hélio Oiticica

Mari Carmen Ramirez, who curated the exhibition, is the curator of Latin American art at the museum and director of its International Centre for the Arts of the Americas. Among the latter’s ambitious collaborations is its work with the Projeto Hélio Oiticica, which includes not only the current showwith its 400-plus-page catalogue and the future exhibition, but also a projected seven volume catalogue raisonné of the artist’s entire oeuvre.

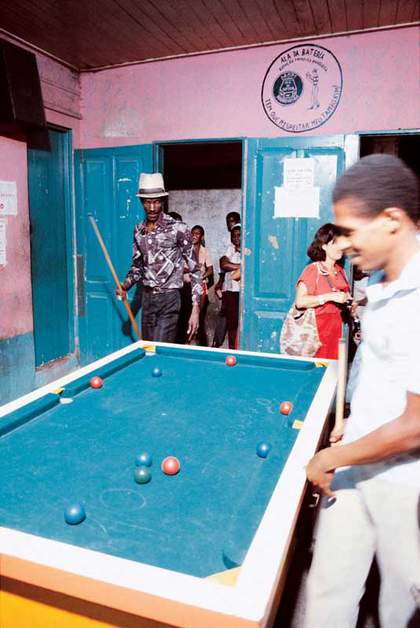

Snooker room in the Mangueira favela during shooting of the film HO by Ivan Cardoso, 1979

Photo: Andreas Valentim

Oiticica, who was born in 1937, grew up in an educated household in Rio. His father was an engineer, maths teacher and entomologist, but encouraged his sons to study art and even worked on assignments with them. Hélio and his two younger brothers, César and Claudio, studied with the Neo-Constructivist artist Ivan Serpa at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio, beginning in 1954. The first pieces in the exhibition are gouaches in muted, dark tonalities that show a remarkable grasp of both colour and form. The tones are subtle and richly textured, while the edges dividing shapes are assured but not rigid. The artist considered this work juvenilia and did not exhibit it later in his life. It was an inspired decision by Ramirez to include it, as it demonstrates how early he developed his technical skills, and also how directly it forms the basis for his next group of work.

Reproduction of Oiticica’s 1968 flag Be an Outlaw, Be a Hero, inspired by the death of Cara de Cavalo, a famous Rio bandit and friend of the artist

© Courtesy Galeria Nara Roesler

Oiticica attended the second São Paulo Biennial in 1953, where he saw works by Picasso, Calder, Mondrian and Klee. Mondrian was the key artist for the Brazilian Modernists of the 1950s, and Oiticica was an ardent admirer, as his writings show. The influence of Paul Klee is also evident in his early work, introducing an element that can take things away from the Constructivist arena. A Klee oil such as Fire in the Evening 1929 gives a clear idea of what was appealing to the young Brazilian: a system-based approach that includes the vitality and unpredictability of natural elements.

Children playing underneath Hélio Oiticica’s NC 1 Small Nucleus no 01 1960

5 pieces

© Projeto Hélio Oiticica

The arts in Brazil in the 1950s flourished – something that had its roots in the country’s Modernist movement of the 1920s. Led by writers Oswald de Andrade and Mário de Andrade and painters Tarsila do Amaral and Anita Malfatti, among others, Brazil established itself as an important centre for generating Modernist ideas. Inspired by a stay in Paris and the discovery of Cubism and Futurism, Oswald de Andrade published his Manifesto of Poetry Pau Brasil in 1924, the same year Breton produced his Surrealist Manifesto. He also helped to organise the historic Modern Art Week in São Paulo, which first exhibited the work of Brazilian Modernist artists. The violent break with academic art that these artists encouraged embraced the incorporation of indigenous, folk and African-based traditions. They are still seen as heroic figures, but in the 1950s their folk tendencies were to a great extent supplanted by the embrace of geometric abstraction, although the underlying principle – that modern art should flee the conventional – remained. Art based in part on Neo- Plasticism and poetry that saw words as objects, as opposed to vehicles for self-expression, became popular in Rio and São Paulo. In 1956 the National Exhibition of Concrete Art at the Museum of Modern Art in São Paulo featured poets and artists from both cities, including Lygia Clark, Hélio and César Oiticica, Lygia Pape, Ferreira Gullar, Augusto de Campos, Haroldo de Campos and Décio Pignatari.

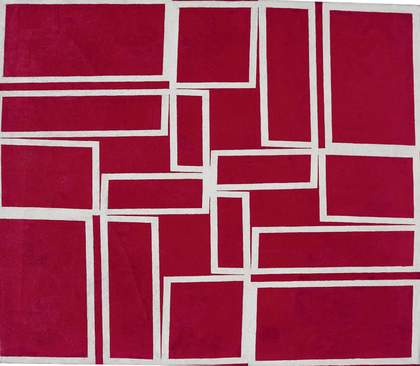

Ivan Serpa

Untitled 1954

Oil on canvas

116.5 x 89.5 cm

Photo: Mark Morosse © Courtesy Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection, Caracas

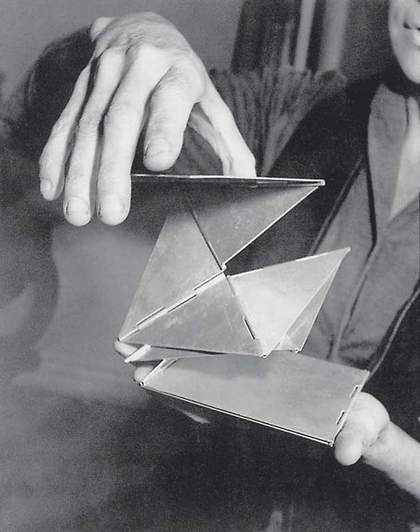

Oiticica briefly joined Serpa’s Grupo Frente, and, influenced by his teacher and by Klee, made Neo-Constructivist works with playful overtones. The group included Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape, who would become internationally known. Clark’s work provides an interesting parallel to Oiticica’s. After making folding geometric pieces in various metals, she, like Oiticica, became involved in performative transformations. Geometric works that give the illusion of space, Oiticica’s early gouaches evidence the precision of his painting, the complexity of his tones and, more importantly, an individual sense of colour – the theme of the Houston and Tate exhibition. In 1955’s Sem Titulo (Untitled) they are natural colours, conjuring flowers and plants, not candy or the colours of man-made plasticity. This sensation of an undefined natural referent is present in all Oiticica’s Grupo Frente pieces.

He was not satisfied with this work, however, and attempted to empty his art of any illusionistic elements. He proceeded to the Sêcos 1956, gouaches on cardboard, in which the unpainted surface emphasises a bland, straightforward quality the artist was aiming for. By now, we can recognise Oiticica’s expert technique, and while this body of work is in the tradition of El Lissitzky, it does not look like a copy of the Russian master. The geometric patterns are those of a unique, though young, voice.

Lygia Clark

Bicho de Bolso 1966

Aluminium

12 x 13 cm

© Courtesy Maria Cristina Burlamaqui Collection

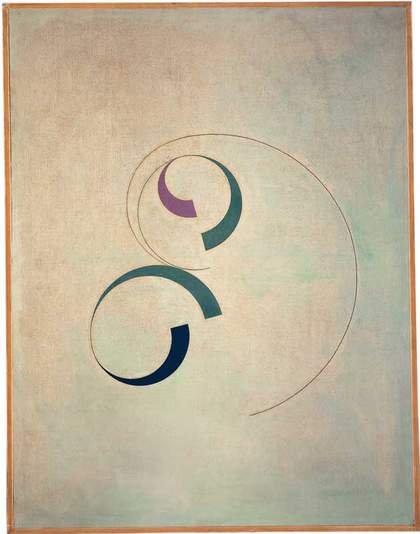

The artist hit his mature stride with the Metaesquemas 1957–8, often painted in gouache on cardboard, again partaking of the surface’s mundanity, but with a graphic punch that is on an entirely different level. Where the Sêcos’ designs feel randomly placed on the cardboard support, the Metaesquemas evolve to full incorporation of the scale of the cardboard sheet. These works are wonderfully balanced experiments in offbeat decoration.

The Houston show, installed in the mezzanine of the museum’s Mies van der Rohe building, allowed the viewer to see work in groups, but also to discern how one group led to the next, revealing surprising continuities throughout the artist’s career. This was useful in stressing the exhibition’s emphasis on colour, but it also clearly displayed Oiticica’s continuing explosion of form. When a transition occurred in his art between Modernism and Postmodernism, it was not the traumatic experience of a nervous breakdown, but rather a heroic act of self-fulfilment. Examining the Metaesquemas together, the viewer could see the artist’s particular use of colour in action. Each is painted in blue or red, but the blues and reds are subtly varied, as are the precise shapes, which just manage to avoid collision or else delicately rub up against one another. They turn from geometric shapes to off-shapes, from rectangles to forms that are like two rectangles slightly skewed and pushed together.

Hélio Oiticica

Metaesquema – Red going through White 1958

Oil on canvas

52 x 60 cm

Courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston © Projeto Hélio Oiticica.

Part of the White Series 1958–9 is not completely white, as it depends on defining black lines to give it its drama. This is similar to graphic letter work by Al Held. Another part does involve pure white canvases. The series brings to mind Robert Rauschenberg’s white paintings from 1951. While quite different in terms of technique, they are similar in aesthetic goals. Both artists, in the 1950s and 1960s, wanted to move into areas where life and art could be interchangeable. The Bilaterals 1959 are Oiticica’s first foray away from the rectangular base. In varied formats, some hung from the ceiling, the artist was experimenting with integrating his work into the viewer’s space, which would become more and more a central aspect of his work.

At this point, he is still rooted in the geometric, Neo-Plastic sense of things. With one bridge, that approach would soon change – a bridge in both colour and shape. In the meantime, in his two-tone horizontal White Series pieces, he creates surrogates for horizon lines. Oiticica is working with casein emulsion mixed with oil, giving the surfaces a non-classical feeling. His painting skill is exciting – the lines that divide one area from another are tantalising, not strictly drawn, but rather painted with a sensitive appreciation of separation, giving them the feeling of natural divisions between sky and sea. Likewise, the painted areas themselves are not monochromatic, but rather pulsating spaces into which the eye can endlessly travel.

The Spatial Reliefs 1960 are part of the bridge to the future. Like the Bilaterals, they are geometric forms suspended in space. Unlike them, they partake of colour – specifically, warm southern colours, reminiscent of Oiticica’s Grupo Frente work, but more fully realised. He is tuning in to his colours, or the colours of his time – endless variations of reds, yellows and oranges. From this vantage point in the Houston installation, one could see these colours ramifying – into the Bólides and beyond that into the pulsating, relaxed forms of the Parangolés. Interestingly, the exhibition included some maquettes for the Spatial Reliefs, and one could see how Oiticica refined and determined his forms in the finished pieces.

There are two other bodies of bridging work - the Nuclei Series 1960–3, in which rectangular bands of colour are modified from a central tone, and the Inventions 1959–62, oil and resin mixtures on wood fibreboard, in which the artist worked in colour on identically sized square panels. The Nuclei were installed floating over a shaped cut in a large rectangular bed of small white stones, giving the impression of a suspension over a pool. One could feel very clearly the interactive element, the suggestion that people and other things were meant to be circulating in and among the nuclei. This idea was expanded in the Penetrables, large-scale shaped areas, in which people were meant to walk or socialise. The Inventions on the opposite wall, in three horizontal rows of twelve pieces each, were not monochromatic, and they were much more than chromatic experiments. Although very close in tone – Oiticica loved to work within a limited range of hot, earthy tones – each is a particular meditation on pigment and its own individual statement. As the poet Haroldo de Campos observed, a Cartesian organisational ability co-existed in Oiticica with a Rimbaudian desire for delirium.

Between the Inventions and the Nuclei on the open mezzanine rested the Bólides – and here the revolution began in earnest. For the first time, Oiticica left Modernism completely behind and fully crossed the bridge into Postmodernism. He was now willing to let real life take an active role in his work, not in the sense of found objects, but in a deliberate attempt to create art that exists on an equal plane to life and can suggest direct interaction with it. The Bólides that are the most evocative are those that make use of pigment, fabrics, earth, or shells. These have a rich quality, as though the materials were bursting out of a Modernist context. Not only are they non-formal, they are also approaching Oiticica’s idea of anti-art. This goal, however, would be more closely approximated in the Parangolés. When he began to frequent the Mangueira favela, the lived experiences in which his art was incorporated became as important as the objects themselves, which are like artifacts. Just as African ritual dance masks or spirit figures retain aesthetic and cultural significance even when separated from their original contexts, so the capes and structures from Oiticica’s interventions impress us with their materials, colour combinations and the gracefully unpredictable ways colours and forms meet and overlap.

The Parangolés 1964–8 are made of a mixture of materials, including polyvinyl acetate emulsion, canvas, cord, nylon mesh, cotton fabric, newsprint and burlap, randomly stitched together, so far from the precision of the early works, yet maintaining the same delicate approach. Even if, on one level, he always stuck to avant-garde principles, his particular take on the life-art nexus was quite different from, say, Duchamp’s. In place of mute, everyday objects, Oiticica quested for the spiritual, the transformational. He also, like the early Brazilian Modernists and Tropicalists, loved himself to be alive to the vital Brazilian popular culture. He transformed his materials into a vivencia, to use the artist’s own word – an interaction with living life.