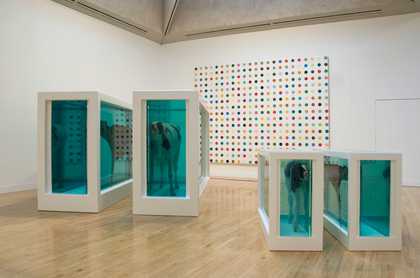

The first Turner Prize I ever saw, as a tremulous teenager day-tripping from Yorkshire, was the 1992 edition. It wasn’t quite a changing-of-the-guard affair, but it was close. Damien Hirst, the show’s obvious star, lost to Grenville Davey in what was, in Turner terms, virtually the last hurrah for the Lisson Gallery’s stable of sculptors, who’d had both the prize and the London art world in a headlock for the previous five years. (The Prize welcomes second chances, though. Its juries gave Richard Long three-consecutive cracks at winning until he finally did so in 1989, while Hirst eventually hoisted the award in 1995. There is precedent aplenty for this year’s shortlist featuring two previous entrants.) What the 1992 Turner Prize first clarified for me was this: besides being a bellweather of contemporary British art practice, it’s a genteel brawl between shape-shifting forces. And refereeing it is a necessarily approximate science.

Seemingly, it always was. Go back to 1987, when the Turner, set up in conscious emulation of the Booker Prize, was three years old. Routinely criticised for comparing apples and oranges, it was at this point gladly welcoming kumquats and bananas too. Were there two more dissimilar painters then working in the UK than Thérèse Oulton and Patrick Caulfield? To complicate matters further, the later was shortlisted for an exhibition he’d curated; thus he might be better compared with Declan McGonagle, nominated for his running of the Orchard Gallery, Dublin. (Up until that year the Turner was not limited to artists, though no non-artist ever won.) Representing new British sculpture, Richard Deacon wiped the laurels; two decades on, this seems like another world. Nevertheless, in freeze-framing a scattering of mavericks being trounced by an ascendant aesthetic tendency, the 1987 list appears in retrospect – to return to the gastronomic metaphor – like a convincing snapshot of the state of the fruit bowl.

As does the list from a decade later, although in the interim everything had changed. In 1997, the year of Sensation, the shortlist, all female, was also 100 per cent YBA. Outside of this, certain international trends were alluded to: the judges’ choice of Gillian Wearing as winner confirmed that video art was now “institutionally correct”, as Colin Gleadell put it in the Daily Telegraph. The shortlist’s inclusion of Angela Bulloch, meanwhile, was a well-timed nod to the emerging continental tendency towards artworks with which the audience actively engaged, as theorised by Nicolas Bourriaud in his influential 1998 book Relational Aesthetics. As Claire Bishop notes in her preface to Virginia Button’s book The Turner Prize, that hasn’t been much repeatedaccentuates the fact that, despite the increasingly global outlook of recent British art, the Turner Prize isn’t necessarily a barometer of how trends outside the UK impact on national practice. An exception might be the (predominantly market-driven) resurgence of painting on the international stage. But even so, where the medium has reappeared in recent shortlists – Gillian Carnegie in 2005 and prize-winner Tomma Abts in 2006 – the emphasis has been on modest, difficult but rewarding work.

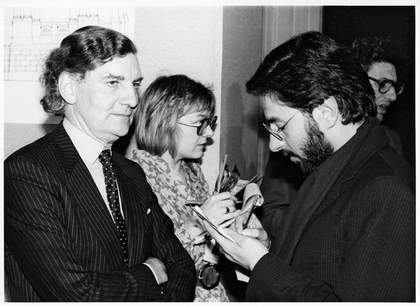

Alan Bowness and Waldemar Januszczak 1984

© Tate archive

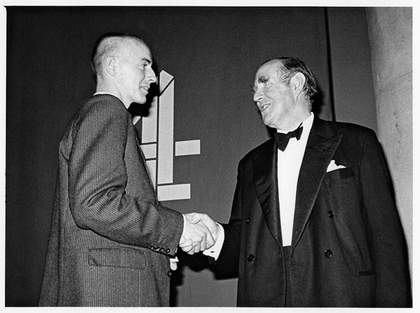

Grenville Davey and Peter Brooke MP 1992

© Tate archive

If certain aversions remain apparent today, particularly with regard to difficult formats such as performance and the increasing turn towards social interventionism, one could hardly accuse the jurors of being hidebound. It’s a long way from 1985 winner Howard Hodgkin’s delicate painterly reveries to the sharp shock of 2001 winner Martin Creed’s notorious installation Work No 227: The lights going on and off, which seesawed an empty room between bright light and relative darkness. And photography, while it has featured on shortlists since the mid-1990s, was recognised as an ascendant medium in 2000 when Wolfgang Tillmans took the prize.

Tracey Emin

My Bed 1999

Photo: Mark Heathcote, Tate Photography

This year’s shortlist, too, feels convincingly of the moment: veined with geopolitics, stylistically heterogeneous and comfortably reflecting the ethnic diversity and globe-trotting tendencies of British artists. (Compare this with the furore over ex-pat Malcolm Morley winning the inaugural prize in 1984 and refusing to travel from the US to receive it). And its exhibition at Tate Liverpool can’t help but tactitly reflect the extent to which British art is no longer rigidly London-centric. Liverpool, after all, is home to the country’s leading contemporary art biennale, and the nation is now freckled with sleek kunsthalle-type spaces for contemporary art. The list is also, in a manner that has increasingly characterised recent years, a relatively sober affair, notably light on media-friendly dramatics.

As such, it’s another sign that at age 23 (or perhaps 22, given that there was no prize in 1990) the Turner Prize is increasingly comfortable in the spotlight. In the past, it has sometimes appeared anxious, aware of being judge itself: in 1989 all four entrants were in their forties at least, whereas when the prize was relaunched in 1991 with a new media sponsor, Channel 4, all except winner Anish Kapoor were in their roaring twenties. Was it happenstance, meanwhile, that following the all-female shortlist in 1997 (previously only one female artist, Rachel Whiteread in 1993, had won, and clearly something had to be done) the number of women shortlisted in the next four years was, in chronological order, three, two, one, zero? An onlooker can nurse paranoia about this, and some self-scrutiny apparently subsists: in the past decade the prize has never been awarded to two artists working in the same medium for two consecutive years, and since there’s no painter in the shortlist this year, that remains unchanged.

But one can also overstate the importance of this apparently unappeasable tinkering. First, because the Turner Prize is a perpetual work in progress, twitchily tracking both an evolving culture and itself. And secondly, because without the klieg light of publicity – which demands endless renovation and attention to surfaces – the prize’s greatest legacy thus far wouldn’t exist. That legacy, of art in Britain, and the range of artistry was midwifed. It was glimmering there in the genteel brawl of 1992, encoded in Hirst’s retinue of fishes in formaldehyde. If we are now somewhere more secure, less flashily pursuant of attention, hospitable to subtlety and diversity, the Turner Prize has not only traced the steps along the way; it has also played no small part in getting us there.