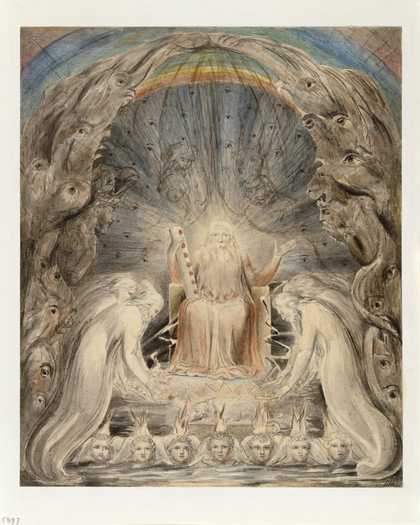

Today the myths of William Blake precede his art and writing. Forgotten for decades after his death in 1827, it was only from the mid-nineteenth century onwards that he was rediscovered by subsequent generations of artist groups and writers, each of whom celebrated characteristics that suited their own interests – for the Pre-Raphaelites he was a fellow medievalist and Romatic, whereas for the early twentieth-century Bloomsbury group he was a true Modernist.

The notion of an eccentric visionary lost in his own fantasy world has, to a certain extent, overly romanticised Blake, for he was also a working craftsman who was fully engaged with the political and philosophical issues of his time. Yet his intellectual and artistic stance was deliberately at odds with his contemporaries, and it is this independent thinking and defiant, obsessive belief in his own creativity that continues to inspire living artists.

Blake’s determination to pursue his own path is emphasised by the declaration from his alter ego Los: “I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Mans.” And here five artists who create their own highly imaginary and allegorical worlds mark the 250th anniversary of Blake’s birth.

html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40/loose.dtd"

Ernesto Caivano

For many years Ernesto Caivano’s intricate ink drawings have described an epic love story, titled After the Woods, as depicted through the flora and fauna of an alternative reality. A contemporary fairy tale, the underlying narrative is that of a knight who becomes a tree and a princess who transforms into a spaceship, yet a single 11 ft (3.35 m) drawing can focus on the exquisite detailing of a plant. Together these numerous studies become an exhaustive exploration and evolution of an alternative universe and eco-system. Caivano says: “The only thing I really admire about Blake’s endeavour is how he was able to build a self-enclosed system of meaning in such a poetic way – I think that is why people keep going back to him… Stories are the way that people relate to the world and anchor meaning, and I think of Blake as someone who spent his entire life building narratives… Blake is trying to unravel a master narrative of his universe – culturally, politically, psychologically, personally, autobiographically and romantically.”

Charles Avery

Charles Avery admits being rather put off by Blake’s drawings at first sight, finding his style to be an acquired taste. Avery’s elegant large-scale pencil drawings, models and texts together represent his singular vision for an imaginary island that is inhabited by a number of iconic characters, such as a platypus monster called Mr Impossible, an aged bather and a large number two. Rooted in modern philosophy, his ongoing Islanders project, which will take more than ten years to complete, takes as its premise the very subject of artistic and philosophical enquiry. For Avery there are two types of artists, those who define arts as “object”, believing what they create is art, and those who define it as “quality”, believing that it is the idea which is the art: “It is to this second class that Blake belongs, as do I… What I feel I have most in common with Blake is that his work was a means of exploring his mind, rather than making artwork… Artists have a unique privilege, which is that of solitude and the opportunity to imagine. In being a visionary one channels that into the work in a very direct way. Artists and philosophers, both naturally and metaphysically, have a common idea: that there is an ultimate identifiable truth, which is their destination.”

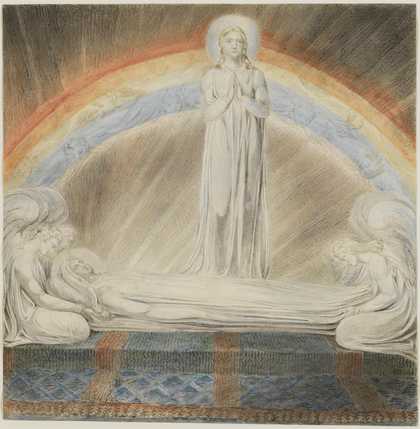

Kerstin Kartscher

Kerstin Kartscher encountered Blake’s poetry before his drawings and illustrations, and for her his “vision is important, and it’s important that it’s more than what is visible”. In her own coloured marker-pen drawings and sculptural installations, she has often focused on the image of a solitary female protagonist in an elegant dress, as if transported from the past and set within a dramatic and expansive imaginary landscape. Like Blake, Kartscher draws from historic, literary sources and more recently the figure has become implied rather than stated in works such as Die Sabinerin, titled after the ancient tribe whose women the Romans abducted to populate their newly built city.

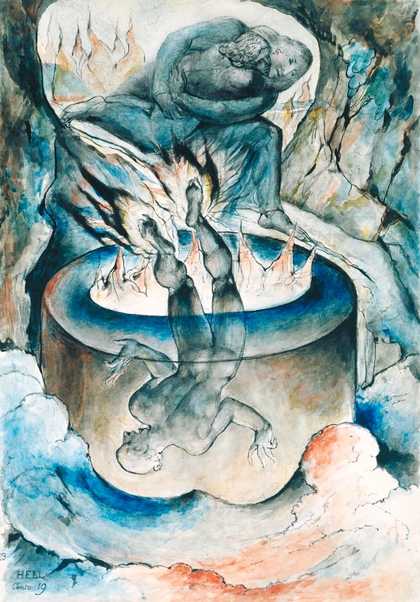

Heiko Blankenstein

Heiko Blankenstein also considers that Blake has had an influence on his own practice, since “he broke with conventions of that time by adopting mysticism rather than straightforward religious doctrines, but also rebelling against a purely scientific way of approaching the world”. Blankenstein sets about creating his own systems for his complex graphic compositions that draw upon the aesthetics of medieval printmaking and combine sources such as the history of alchemy, Far Eastern rules of perspective and chaos theory. Ultimately, like Blake, he is interested in what happens beyond the realms of rational thought.

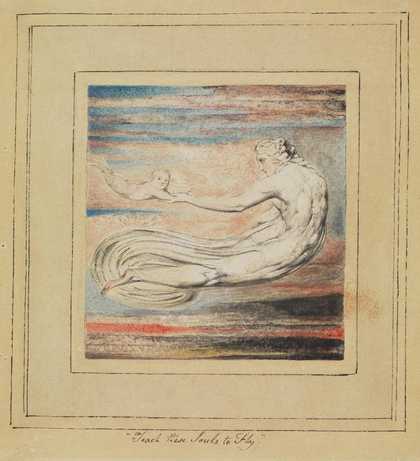

Dirk Bell

Dirk Bell was immediately impressed by William Blake’s illustrations, which he encountered at a young age, finding them to be “urgent, powerful and loaded with the drama of life. Every picture I know by Blake looks as if it needed to be painted, as if it needs to be seen”. Bell’s watercolours, drawings and sculptures have a mesmerising visceral presence – akin to a quality he describes in Blake’s work as “anti-luxurious, like a sign hanging, or a bell banging”. His images of shadowy figures placed alongside found photographs or customised domestic objects offer a darkly romantic vision of a sensuous, dreamlike world.