SIMON GRANT Can you remember when you saw your first Rothko in the flesh, as opposed to reproduced in art books?

BRICE MARDEN It was at the Sidney Janis gallery in New York in 1958. The paintings seemed huge because the gallery was small and divided into several rooms with low ceilings – these 9.5 ft works were literally covering the walls. When it is just you and several of these paintings in one room, it is an incredible experience. I remember one in particular, Browns 1957, which was white on top and blueish green on the bottom. I’ve not seen it since. When you stood in front of them you were just taken into a completely different world. At the time I was a student (at the Boston University School of Fine and Applied Arts) and immersed in a figuratively orientated conservative school, but my tendency, my leanings were towards Abstract Expressionism. At that time, I didn’t know much about it aside from what I was reading in ARTnews. So I would be standing in front of these paintings trying to figure them out, and I realised that what I liked about Abstract Expressionism was that it didn’t pay to get terribly analytical about it. It was better if you just went with the painting.

SIMON GRANT Did that response correspond to any notion of beauty, or was that an unfashionable thing to talk about at the time?

BRICE MARDEN I think we were discussing beauty at the time, yeah. We looked at a lot of beautiful painting – so beauty was not a verboten subject.

SIMON GRANT What was it about looking at the paintings that struck a chord?

BRICE MARDEN Well, I can tell you what kind of effect a Rothko can have. I had what you might call a transcendental experience in the early 1960s. I was driving in my car from San Francisco to Monterey in California and going through this area that’s known as the artichoke-growing capital of the world. They grow in long rows over gently sloping hills. I remember that there was a very peculiar light, and there was a storm approaching, and I felt I was in a Rothko painting. I remember the sensation very distinctly and made an etching about it soon after.

SIMON GRANT When you say like being in a Rothko, what do you mean?

BRICE MARDEN That you’re in a space – an indefinable space, but it is having an effect on you physically. You feel engulfed, totally surrounded by it. Last year I read that Rothko once said that the ideal distance from which to view his paintings is eighteen inches. So I do as he suggested whenever I am in front of one. And it makes a huge difference. You become much more conscious of every little nuance, which probably at some other time I had thought were just little accidents in his painting process. I realised how carefully they were painted.

SIMON GRANT Rothko had talked about wanting people to cry in front of his paintings. By asking us to be intimate with them, do you think he was interested in creating what Dore Ashton referred to as the sense of an epic drama?

BRICE MARDEN Yes, I totally believe that. Recently, I saw this exhibition of African sculpture from the New Orleans Museum of Art at Penn State University, and in the catalogue there was a passage about the Bambara Mask and how it is made: “Masks are carved in the bush and every sculptor has his own ‘recipe’ for investing a mask with Nyama. Herbal substances mixed with earth are applied to the mask which refers to no one animal but is a metaphor for all that is in the bush, the huge mouth may be that of a hyena.” Essentially, the writer is talking about how the individual artist is creating the spirit. For years I’ve been going around embarrassed by the fact that I believe there can be more to a painting than what’s there. I disagree with Frank Stella’s line that what you see is what’s there and have always supported the romantic notion within art. At the beginning of my career I thought it was a defence because I was a very non-intellectual painter, so I would go to the other extreme.

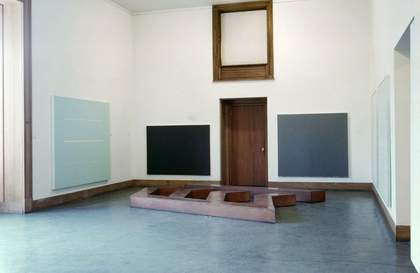

SIMON GRANT In some of your earlier exhibitions you were compared with a number of Minimalist artists, but you have said that you see yourself as more of an Abstract Expressionist. How about a Romantic Minimalist?

BRICE MARDEN Oh, definitely! In fact, in 1967 I was in a group show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia called ‘A Romantic Minimalism’, along with artists such as Carl Andre and Robert Mangold. You couldn’t paint the same way as the Abstract Expressionists painted because you couldn’t use that space or structure which they had developed from Cubism. So the next part of the process was to aim for a more minimalist space. But in my case, I never gave up on the whole idea of paint being part of the expressiveness of that space.

Brice Marden

A Romatic Minimalism 1967

Installation view Institute of Contemporary Art University of Pennsylvania

Courtesy Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania

SIMON GRANT Did that manifest itself in your materials and your painting process? Rothko, for example, used tinted washes for his paintings.

BRICE MARDEN Yes, it had to do with surface, with the application of the paint. In my case, and in Rothko’s, with the scratches and scrapes and the colours coming through from below, it might look like a monochromatic surface, but it really never is. There are real evidences of drawing. I remember being very conscious of how you spread the paint on the surface of a canvas, of how it got to the edge and how it went around the corners. How do you draw your way vertically and horizontally around a corner? These were issues one would consider. The issue of how you broach the outer edge of the painting was a big one for Rothko too. Sometimes he would put on these taped borders, then later he would take them off to leave a weird edge. It was a careful consideration about where the painting stopped in relation to the world. My earlier paintings, done with a mix of melted beeswax, were much more physical. They are still physical, but now I try to keep the layers very thin. Rothko was a physical painter, but the physicality goes into an atmosphere. Mine doesn’t. It becomes more a realist thing. Instead of going towards Rothko, it goes towards Jasper Johns.

SIMON GRANT Johns’s first retrospective at the Jewish Museum in 1964 made a big impression on you, as did a show around that time of Alberto Giacometti’s paintings in Paris. Then in 1966 you had your first New York exhibition at the Bykert gallery, where you showed some grey paintings, as well as horizontal ones that were white at the top and black at the bottom. These seem to predate Rothko’s late Black on Grey series…

BRICE MARDEN I didn’t know that Rothko was doing those at the time. Actually, a lot of artists were making grey works around then – Robert Mangold was making grey paintings, Robert Morris did a sculpture show at the Green Gallery where everything was painted grey. I was doing grey paintings because I was trying to get involved with colour ideas. I felt I didn’t know anything about it, so the way to do it was to get back to the basic thing and work up from that. Grey is a complex colour – it can be dealt with in terms of both neutrality and colour. A lot of the grey in Richter’s paintings is about its neutrality. For Cézanne it was about the ability of grey to be natural.

SIMON GRANT You have talked about colour as a way of arriving at light. How do you regard Rothko in this respect?

BRICE MARDEN He transforms colour. It stops being colour and it becomes a light. It didn’t seem to me he was trying to make the colour of a landscape that he knew.

SIMON GRANT So is that where your path with Rothko diverges?

BRICE MARDEN Well, I always felt that when it comes to colour and light, it has to do with some sort of landscape. Or a specific place that I know, be it in Hydra, the Caribbean or the Hudson River. It is not that I’m trying to depict it, it’s just that if you feel, if you’re really working, wherever you are, it gets into the painting. Some say that Rothko was very influenced by a Bonnard show and the painting changed after that, but there had always been this Milton Avery influence in the earlier paintings. Also, there’s a great intelligence to these paintings; you can tell the guy’s really smart, but he’s not trying to display it, it’s just built into the work. It is part of the resonance of the pieces.

SIMON GRANT Rothko has long been considered a modern master, but how do you think he is perceived today? Is he an artist that people can keep coming back to?

BRICE MARDEN Yes, I think so. There are certain times when his paintings just don’t look any good. I don’t know if that’s because they get dirty, or if some are losing their colour. Then a couple of years will go by and suddenly his work will look incredible again. In an auction last year I saw two fabulous late Rothkos – two Black on Grey paintings. They looked so powerful they killed everything else around them. I think his late paintings are the best ones. They are incredible. I believe he had allowed himself to go to some sort of extreme. I once saw a group of these all piled together at the Rothko Foundation and remember being awed by the activity, the breadth and the range that he demonstrated.

SIMON GRANT When you had your retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2007, did anybody mention your work in connection to Rothko?

BRICE MARDEN I can’t remember people bringing up Rothko at all, though I thought some of them looked very Rothko-esque to me, in particular the Grove Group paintings. And a painting such as Adriatic 1972–3, I don’t think I could have made that without Rothko. Even Rodeo 1971, although that is a much rawer painting than anything Rothko would be able to agree with. I go in and out of my relationship with colour. Sometimes I’m much more concerned about drawing, and when a lot of the drawing problems get solved, I get involved with colour. Those paintings were really involved with colour. There’s also the kind of landscape idea that you can associate with certain aspects of Rothko, although we never think of him as painting the landscape. But, then again, I think Rothko is the ultimate landscape painter.