Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, devised a now legendary flow chart for his pioneering exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art 1935. Using an intricate network of straight and curved arrows, he created a genealogical tree for modern art in which Cubism was, of all the ‘isms’, by far the greatest progenitor. Seven arrows radiated from Cubism to spawn Futurism, Dada, Orphism, Purism, De Stijl, Suprematism, Constructivism – plus their various offshoots such as Surrealism.

Picasso and Modern British Art is a comparable attempt to chart the trans-Manche influence of the founder of Cubism. Here too, as it were, seven ‘arrows’ radiate from Picasso to seven of the British twentieth-century artists he influenced: Duncan Grant, Wyndham Lewis, Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, Graham Sutherland and David Hockney. A room will be dedicated to each artist, with the relevant fertilising Picassos alongside. These will alternate with rooms that document Picasso’s exhibitions in Britain, and the activities of his collectors and critics here.

The Spanish artist’s future biographer, collector and amanuensis, Roland Penrose, claimed that when Picasso first left his home country in 1900, his ultimate destination was going to be London rather than Paris, because of his anglophile father’s love of English furniture and clothes, and his own love of the Pre-Raphaelites and Edward Burne-Jones – as well as his obsession with the swashbuckling adventuress Lady Hester Stanhope. Picasso’s early genre scene, Science and Charity 1897, had been inspired by a Tate work, Luke Fildes’s The Doctor 1891, which he knew in reproduction. As he moved beyond sentiment and symbolism, however, he must have realised that Paris would be more congenial to his new artistic ideas.

Several British artists and critics came across Picasso’s work in Paris before 1914, but they were largely uncomprehending. Augustus John was one of the first to see Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907 when it was exhibited in the artist’s studio, but it had no impact on his work, and Picasso later dubbed him the ‘best bad painter in England’. His first visit to London took place only in 1919 with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, for whom he designed sets and costumes. He seized the opportunity to dismiss most English art as ‘sweet and pretty’.

Picasso would have been taking aim in particular at the Bloomsbury Group’s Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, and their Omega design workshops, though it was in fact the leading Bloomsbury critic Roger Fry who had first introduced him to British gallery-goers – to almost universal derision. Fry included his work in his two influential exhibitions of modern French art, which he dubbed Post-Impressionist, in 1910 and 1912–13. In the second show he charted Cubism’s progress with twelve paintings and three drawings, and then in 1914 exhibited photographs of Picasso’s revolutionary mixed media constructions. Fry never wrote about his collages or constructions, however, and the only Picasso he bought was a small work on paper, the Cubist Head of a Man 1913. The critic’s formalist interpretation of these works was to be hugely influential, especially in New York where he worked for a while as a museum curator. For Fry, Cubism was ‘a purely abstract language of form – a visual music’. This conception of Cubism as a harbinger of abstraction shaped Barr’s Cubism and Abstract Art, and the post-1940 art criticism of Clement Greenberg.

The future leader of the English Vorticists, Wyndham Lewis, encountered Picasso’s work while living in Paris from 1902 to 1908, and his take on Cubism was diametrically opposed to Fry’s formalism. The Theatre Manager 1909, a small drawing in ink and watercolour, is the first work by a British artist to be influenced by the Demoiselles. A rather beleaguered looking theatre manager sits before a desk poring over the text of a play. He is surrounded and dominated by a group of standing clothed men and – far too close for comfort – a nonchalantly naked woman. The style is gauchely schematic, with jagged lines and elongated ‘primitive’ faces. He was attracted to Cubism by what he took to be Picasso’s love of the ‘hideous and banal’, but this drawing already demonstrates Lewis’s lifelong penchant for caricature and social satire. He ultimately learned more from the Italian Futurists, who put Cubist forms at the service of dynamic narratives, than the more hermetic Picasso, whom he later criticised for his limited subject matter and for being (post-1914) too tasteful. In inimitable style, Lewis concluded that Picasso was ‘a gnome-like child’ – perhaps in part because of the small-scale of most of his Cubist work.

The golden age of British engagement with Picasso stretches from the 1930s to the 1960s. Various phases of his work were the key catalysts for the careers of Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson and Francis Bacon. Moore and Bacon were inspired by his most recent neo-classical and Surrealist works. The former’s petrification of Picasso’s lumbering beach figures is one of the best known episodes in modern art. It was, of course, a deliberate mistranslation, for Moore’s reclining nudes are more taciturn than anything by the Spaniard (whose figures look fidgety and fretful by comparison), and his mimicking of naturally worn stone evokes a damp pastoralism in contrast to Picasso’s sun-baked dryness. Bacon was to become one of the few English artists Picasso admired. Picasso’s eerily pantomimic Dinard Bathers 1928–32 were an early revelation, yet Bacon infused his own figures with an apocalyptic sublime that owed just as much to the visionary pyrotechnics of Blake and Turner. Nicholson, an aesthete in the Fry mould, was influenced by various phases of Cubism – though the watercoloury limpidness of his still-lifes, both painted and in low relief, is very much his own.

All three of these major British artists visited Paris (Moore famously observed that the price of a return train ticket to the French capital was much less than one to Yorkshire: plus ça change). Nicholson became a friend of Georges Braque, and though he met Picasso only a few times, he felt great affection, referring to him by the nicknames ‘Piccy’ and ‘Picz’. Whether the development of their art would have been significantly different if they had remained in England is a moot point. Ever-increasing numbers of Picassos were included in British exhibitions, and could also be seen in reproduction in books and magazines. Private collectors such as Penrose and Douglas Cooper, taking advantage of lower prices during the economic depression, were forming some of the best Picasso collections in the world. Weeping Woman 1937 is the most famous of Penrose’s Picassos to enter the national collection – in 1987 – and he also negotiated the purchase from Picasso in 1965 of The Three Dancers 1925, the key work of his Surrealist phase.

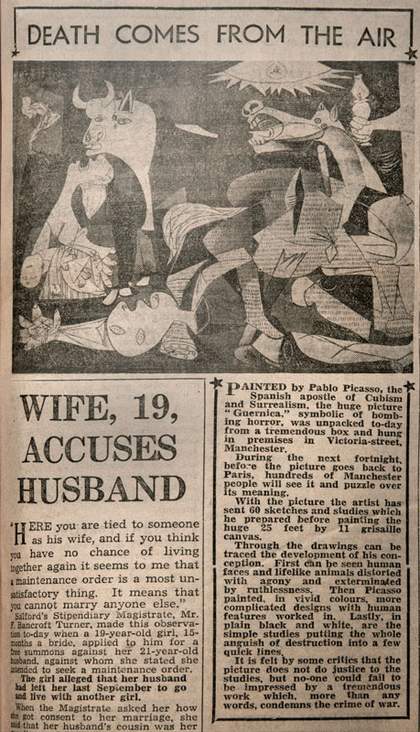

During the 1930s the critic Herbert Read, partly influenced by Freud and the French Surrealists, saw Picasso as an intuitive artist in whom conflict raged but was ultimately resolved into a higher unity. Conflict was indeed to be the subject of Picasso’s largest painting, Guernica 1937, and the artistic decade in Britain culminated with its exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery (as well as Oxford, Leeds and Manchester) in support of the Spanish Republicans. At the Whitechapel it was seen by 15,000 people, each of whom gave a pair of boots as the entrance fee. That it received a mixed rather than wholly hostile reception can be viewed as a sign of growing acceptance. In the post-war period, a successful exhibition was held of Picasso’s wartime paintings at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and a huge retrospective at Tate in 1960 was seen by half a million visitors. The Spaniard’s membership of the Communist Party, which he joined in 1944, did little to harm his prospects in this country during the Cold War.

One could easily mount several more exhibitions to chart Picasso’s influence on British art, and Tate Britain’s ‘magnificent seven’ are far from being the last word on this particular subject. The show is heavily biased in favour of figurative painting – which is in itself a rather English preference – and it culminates in the set designs of the ubiquitous David Hockney. Picasso’s British friend and biographer John Richardson is also symptomatic of this recent trend to treat the artist primarily as a figurative painter: for Richardson, even the most austere Cubist works are genre scenes with ‘hidden’ biographical messages about Picasso’s love life.

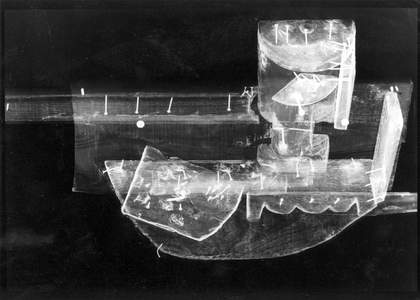

If a show on this same subject had been mounted 40 or 50 years ago, the post-war section would have been very different. We might have seen some collages by the Independent Group artists (collages are conspicuous by their absence here), and abstract reliefs by Victor Pasmore. A 1970 version of Picasso and Modern British Art would have culminated with the abstract constructed metal sculptures of Anthony Caro, who was hugely influenced by Picasso’s sculptures and collages.