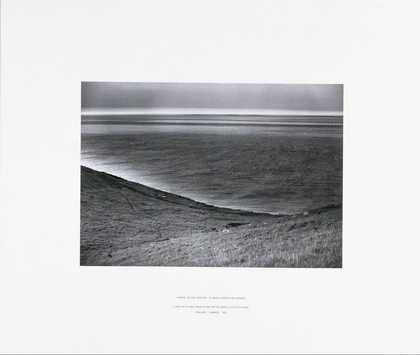

Sarah Martin on Hamish Fulton’s France on the Horizon 1975

Hamish Fulton

France on the Horizon (1975)

Tate

Living and working on the north Kent coast as I do, the horizon line is never far away, and it is easy to become obsessed with that narrow, constantly changing band of light and colour where sea dissolves into sky. I think that is partly why Hamish Fulton’s photograph and text work France on the Horizon resonates so powerfully with me. An arrestingly simple, almost abstract view over the English Channel around dawn, the photograph captures an instant in a landscape at once timeless and familiar as well as alien and unknowable. Like all of Fulton’s early photo works, it is the result of a moment’s pause on a solitary walk, in this case a one-day, 50-mile circular trek via Dover.

Walking for Fulton is all about a lived experience, and to take part in one of his group walks, as I have been lucky enough to do on a couple of occasions, is to commit to that experience, to see it through to the end despite the vicissitudes of the particular terrain or the weather. This isn’t walking as heroics, however, but rather about the meditative state that walking can induce. France on the Horizon encapsulates the spirit of that idea perfectly for me and, though I hesitate to quote Romantic poetry in relation to an artist as avowedly conceptual as Fulton, I can’t help thinking of the closing lines of my favourite Keats sonnet whenever I look at this image: ‘… on the shore/Of the wide world I stand alone, and think/Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.’

– France on the Horizon was bought in 1981. It has been loaned by Tate for Hamish Fulton’s exhibition Walk at Turner Contemporary, Margate, 17 January – 7 May 2012. Turner and the Elements, also at the gallery, includes works from the Tate Collection and runs from 28 January to 13 May 2012. Hamish Fulton: Walk is at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, 15 February – 22 April 2012. Turner Contemporary is a partner of Tate, and exchanges programmes, ideas and skills with the Plus Tate network of visual arts organisations across the UK.

– Sarah Martin is head of exhibitions at Turner Contemporary, Margate.

Simon Martin on Edward Burra’s Dancing Skeletons 1934

Edward Burra

Dancing Skeletons (1934)

Tate

As a Cancerian, I am supposed to be especially susceptible to the power of the moon. While I might not find myself affected by lunacy when there is a full moon, it is perhaps true to say that I have always been drawn to images of it. Moons abound in paintings and poetry. Romantic silvery moons, full harvest moons, but rarely are they like the kooky one in Edward Burra’s 1934 Dancing Skeletons, with its skeletal grin and socket-like eyes. Perhaps the idea of the ‘man in the moon’ is part of our collective need to humanise the unfamiliar, to give human emotions to a huge lump of rock in order to make outer space seem less threatening. But Burra was not interested in making comforting images. In his arthritis-ridden hands, watercolours of flowers could be imbued with an undercurrent of sinister energy, quite unlike any other artist. He once confided to a friend: ‘Everything looks menacing; I’m always expecting something calamitous to happen.’

This is no harvest moon looking down benignly on a pastoral scene. Instead Burra, that indefatigable chronicler of 1930s cafés, Parisian bars and Harlem nightclubs, has revealed the dark side of the night – for this moon grins down at a macabre troupe of dancing skeletons. You can’t help but smile, yet feel unnerved at Burra’s gallows humour. When I was reading his witty letters in the Tate archive while working on a new monograph and exhibition, his passion for the cinema came across strongly, particularly his relish for horror movies. It makes me wonder whether he had in mind the image of a spaceship landing in the moon’s eye in the 1902 French science-fiction film Le Voyage dans la Lune, or perhaps Disney’s Skeleton Dance cartoon. But, more than anything, Burra’s moon is the spitting image of Jack Skellington in Tim Burton’s 1993 animated film The Nightmare before Christmas. I wonder what he would have thought of his work inspiring a character in a Disney animation? He had, after all, designed the sets for the horror sequence of a little-known film called A Piece of Cake in 1948. Appropriately, a verse by Tim Burton encapsulates its macabre power: ‘I am the shadow on the moon at night/Filling your dreams to the brim with fright.’

– Dancing Skeletons 1934 is currently on loan to the exhibition Edward Burra at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester (until 19 February 2012). It was purchased in 1939.

– Simon Martin is the author of the new monograph on Edward Burra (Lund Humphries), and head of curatorial services at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester.

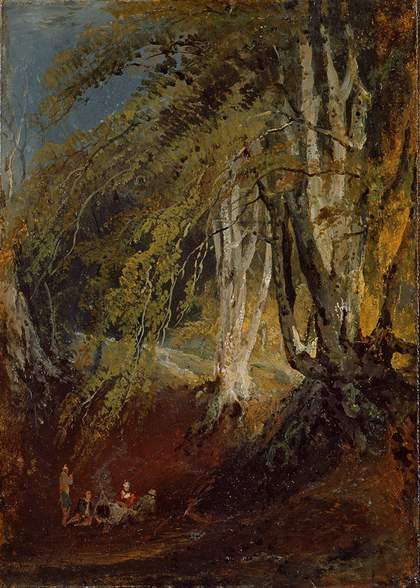

Brian Muelaner on J.M.W. Turner’s A Beech Wood with Gypsies round a Campfire 1799–1801

J.M.W. Turner

A Beech Wood with Gypsies round a Campfire 1799–1801

Oil on paper laid on panel

17× 19 cm

Courtesy Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

What intelligent or even interesting things could a simple tree specialist say about a great work of art, even if it were a tree-related image? I spend my working life looking at trees in great detail, trying to interpret their form, how each has reacted to external and internal forces shaping their unique identity. I imagined that – in writing this short piece – I would bring this same analytical approach to the trees in the painting.

But the more I looked at the picture, the more I saw, and the more I saw, the more I looked. Interpreting the form of the trees came naturally, instantly seeing two prominent beech trees which looked like they were last coppiced about 100 years previously. The one in the forefront could be at risk of tearing itself apart due to the physical stresses caused by its heavy limbs, and might also be in danger of slipping down the bank over time.

It wasn’t the trees which kept drawing me deeper into this painting, it was the way J.M.W. Turner dwarfs the small band of gypsies set within a hollow within the beech wood. This gives the impression they are in hiding and have a need for anonymity, however their relaxed postures around the campfire dispel the notion. They do not appear furtive; indeed, you can almost hear their jovial banter.

Is Turner actually depicting the gypsies’ position in society: outsiders, even outlaws, but with total acceptance of their position, maybe even revelling in it? How many others would feel this comfortable camping out in a dark damp forest of twisted old trees?

– A Beech Wood with Gypsies round a Campfire is on loan from the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. It is currently not on display.

– Brian Muelaner is ancient tree adviser for the National Trust.

Steven Claydon on Walter Sickert’s Queen Victoria and her great-grandson c.1936

Is this painting anachronistic? After all, its subject matter was nearly a half century out of date even at its time of manufacture. I see no anachronism; I see a fizzing, maudlin, technological, elegantly nihilistic and curiously futuristic painting. A purposely follyfilled attempt at the mechanical reclamation of an impossible and unattainable past, painted perhaps from the fictional perspective of a dissonant near future.

For me, Walter Sickert’s later works leapfrog avant-garde germinations and experimentation of the early twentieth century and embody a kind of default existentialism. More precisely, the self-reflective, existential science-fiction of Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape and prognostic introspection of Stanislaw Lem’s book Solaris.

Sickert subtitled certain of his later works Echoes, and I think they occupy the same shimmering retro-speculative territory conjured decades later by a new generation of artists and writers wrestling with the aftermath of near apocalypse. In particular, this painting reminds me of Beckett’s Film, made in the twilight of his career and featuring Buster Keaton.

These paintings were scaled up from one of countless press cuttings collated over decades (a mode of retrieval akin to the contemporary pursuit of scouring the internet for various manifestations of digital material), and transferred to a two-dimensional framework-gridmatrix-membrane. The transmission or transfiguration from the document via a grid transforms the act of painting into the construction of a loge or graph with cells or repositories that represent a portion of received information, or the sum and measure of their own production.

There is no concession here to the suspension of disbelief. As with the work of Bertolt Brecht, we are under no illusion that we are witnessing a fabrication, and I think these works contributed subtly to figurative painting’s abdication of validity right under the nose of the academy. Democratic but illusive, they defy traditional readings; they neuter sentiment and sap narrative. They are positively charged negative things. Augmented renderings of documents that suggest the emblematisation of collective memory and refigure our relationship to nostalgia via the questionable veracity of documentation.

The late works of Sickert are beautiful, curious things that for me invoke parallel dimensions somewhere very close to the surface of work, electric and almost palpable within the membrane, a concoction of ill-portent quicksilver and sentient sludge that emits obscure low wavelength signals…passive-aggressive psychic violence.

– Queen Victoria and her great-grandson is on loan from a private collection, but is not currently on display.

– Steven Claydon’s exhibition, Culpable Earth, is at Firstsite, Colchester, 4 February – 7 May 2012.