I think that one of the things that people tend to look for too much in art is meaning. And they tend to project meaning much faster than I would like them to. If I was a dictator, an art dictator, I would tie them up and say: ‘Here, look at this. And look at it again, and look at it again’. Vija Celmins in conversation with Robert Gober, 2004

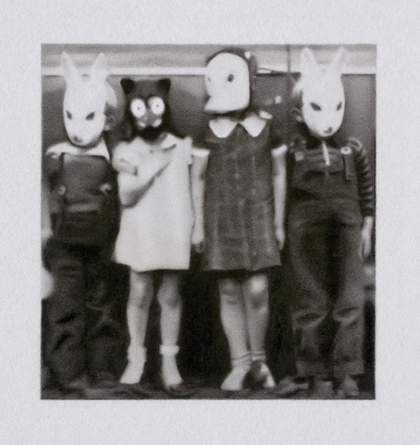

Paul Chiappe

Untitled 48 2010

Pencil on paper

3.6 × 3.4 cm

© John K.McGregor, courtesy Paul Chiappe and Madder 139

The rapid flow of imagery from television, cinema and the internet is now accepted as a dominant source of contemporary visual culture, yet an increasing number of artists today are offering forms of resistance to the fleeting experience of images. Although working mainly with figurative motifs, they are less concerned with traditional notions of resemblance or objective truth than with taking images, often found photographs or reproductions, out of this incessant flow, and reworking them to create a sense of visual intrigue and material presence that entices the viewer to stop and look at the work slowly and carefully.

They do this by deploying the deliberately unremarkable properties of drawing, attracted by its economy of means and fluidity as a medium that allows each artist to reinvent it. This doesn’t mean that they limit themselves exclusively to drawing. In fact, all of the artists included here – Vija Celmins, Anna Barriball, Trisha Donnelly, David Musgrave, Peter Peri, Paul Sietsema and Lucy Skaer – also work in painting, sculpture or film and show their work in configurations that are not determined by medium. They may not constitute anything like a cohesive group, but they are all using drawing to reinvigorate representation and image-making, producing resolved and carefully worked pieces. They share a disregard for clichéd ideas of drawing as being best suited to tentative gestures of immediacy and spontaneity, instead investing time, skill and preparation into the production of their art.

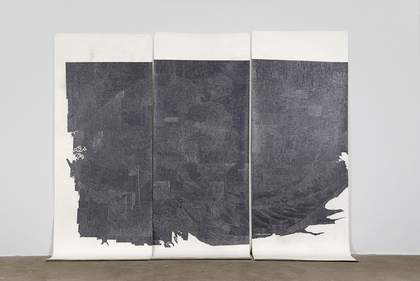

Lucy Skaer

The Great Wave (Expanded) 2007

Permanent marker and pencil on paper

Three panels, 150 × 141cm each

© Lucy Skaer, Courtesy Doggerfisher

Dove Allouche

4 248 m (Chutes de Séracs) 2011

Lead pencil and ink on paper

© Dove Allouche, courtesy Gaudel de Stampa, Paris

Nowadays, there is no longer a question over whether drawing is a primary rather than secondary or preparatory discipline. Back in the 1960s artists such as Sol LeWitt and Mel Bochner showed how drawing in its widest sense moved to the heart of their quest to redefine the very terms of art practice. Its currency was later confirmed by the resurgence of interest in drawing-based work during the 1990s. At this time, William Kentridge, Raymond Pettibon and a host of younger artists brought the medium to the forefront of contemporary practice with work that followed in the wake of a revived interest in expressionism and narrative. More than a decade later, the artists discussed here are also creating figurative images on a variety of themes, but are not interested in telling a story, or trying to offer a window on to the world, or indeed in making expressive gestures. They portray the objects and images with which they choose to surround themselves, rather than bear witness to a constantly evolving interior or exterior world.

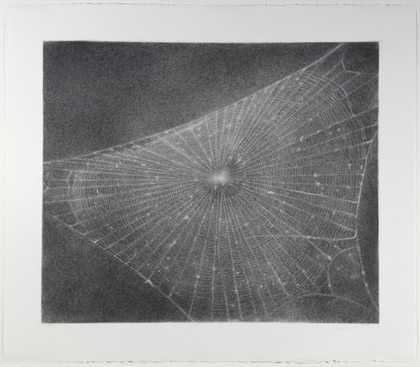

Vija Celmins

Web #1 (1999)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Continuing a line of enquiry that artists such as Vija Celmins, Jasper Johns or Ed Ruscha were exploring in the 1960s, they set out to re-engage with notions of representation, and in so doing overthrow Greenbergian concerns with only the formal, abstract properties of painting and sculpture. In contrast to her peers, Celmins’s highly distinct work has only received the international attention it merits in the past fifteen years or so. Yet younger artists have always admired her paintings and drawings depicting desert scenes, star-filled night skies and oceans. British artist David Musgrave included her work in Living Dust, an exhibition he curated in 2004, and in the catalogue describes her drawings as ‘objects as much as views, and the kind of looking they imply is both intimate and impersonal, an afterglow of the operations of non-human mechanisms. The subjects of the images, while they share the quality of suggesting vastness, a resistance to framing, are not the point – a photograph could convey that far more efficiently. It’s rather the narrow but infinite gap between immaterial perception and its material recording that is their enduring content.’ Celmins’s route to her subjects is always mediated through a photograph, but can be understood as a desire to paint and draw what she saw in the immediate environment of her Los Angeles studio.

She went on to concentrate exclusively on drawing for a sustained period, eschewing the discipline of painting in which she was trained. She put this shift in focus down to a ‘realisation that the image and the support could unify, and the way to do it was through pencil’, spending the next fifteen years exploring the simple materiality of graphite and charcoal on paper to create some of her best-known works. Celmins has repeatedly returned to the same images, which recently include spiders’ webs, as they ultimately offer a familiar vehicle for interrogating the subtle differences in pencil, in her own mood and in her handling of space. She holds the viewer’s gaze by evoking infinite depth in her images, and yet they constantly remind the eye of their inescapable flatness, being nothing more than monochromatic graphite sitting on the surface of the paper.

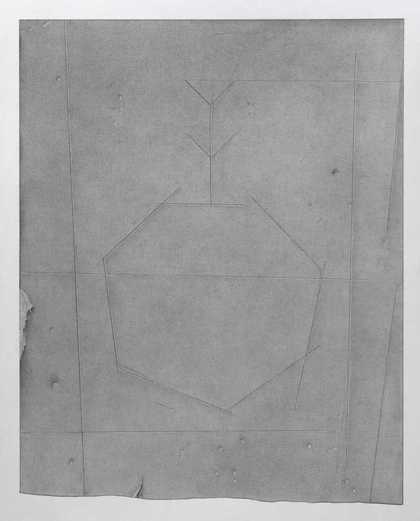

David Musgrave

Plane with inverted figure 2007

Graphite on paper

630 x 503 mm

© David Musgrave

Robert Gober

Untitled 2003

Pencil on notebook paper

15.2 × 24.1cm

© Robert Gober, courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York/SCALA Archives

Musgrave’s own drawings, like his sculptures, instil seemingly throwaway images with a gravity, complexity and subtle presence that make the viewer look more carefully. Like Celmins, he works with a limited range of pictorial motifs. His recurrent subject is that of the stick figure, or a Golem, which in Jewish mythology was a clay figure brought to life through the evocation of a sacred symbol. Most of his drawings commence with a pre-made source image that Musgrave has created, for example an upside-down stick figure, apparently quickly scrawled on card for Plane with Inverted Figure 2007 and resulting in a lightly toned drawing depicting the card, its distressed surface and embedded image in meticulous detail. Other works start with slight figures made from scraps of paper, or masking tape, that test the limits of recognition as a means of slowing down the usual instantaneity of identifying the human form. As writer and curator Kate Macfarlane comments: ‘His imagery resembles archeological fragments or graffiti incised into stone.’ And their trompe l’oeil effect recalls the perplexing still-life paintings of Edward Collier (active 1662–1708), exemplified in A Trompe l’Oeil of Newspapers, Letters and Writing Implements on a Wooden Board c.1699. Musgrave’s drawings imbue fictional compositions with a compelling veracity.

Peter Peri

Detail of Morning Bell (Triptych) 2004

Graphite on Paper

Detail 25 x 33 cm (25 x 87 cm)

© Peter Peri, Courtesy Bortolami Gallery

Although the drawings of fellow British artist Peter Peri differ in subject and style from Musgrave’s, they share an uncanny ability to be captivating as representative images, while at the same time reminding the viewer that they are merely pencil marks on paper. His graphite drawings on unbleached paper of strange figurative objects or unspecified architectural locations can seem both confusing and intriguing. Like his paintings, they evoke the language of an earlier era in art, and yet they have a presence that locates them in the here and now. Batchelors 2008 features tower-like sculptural forms that appear monumental but give no indication of scale. They seem to be made up of organic life forms or tiny hairs that defiantly escape the imagined outlines of the objects depicted as if they have a life of their own. On closer inspection, the falling shadows ignore perspectival logic and the sides of the structures sit at odds with each other, disrupting the spatial illusion.Head 10 2008 portrays a three-dimensional structure reminiscent of a modernist sculptural bust on a plinth. Yet the legibility of the image breaks down as the eye is drawn to the detail of the delicate lines that make up the forms. The viewer is pulled between the spatial depth of the image depicted, then back to the surface of the paper by the detail of the pencil line – an action that one critic has described as oscillating between the ‘microscopic and the macroscopic’

The way in which these artists and their peers in the United States are testing the limits of how drawing can reinvent ideas of representation is perhaps reflective of a growing number of artists concerned with the specific material qualities of their chosen discipline. (Examples of this can be found across several art forms, such as Tacita Dean’s dedicated investigation of the unique qualities of 16 mm film.)

Paul Sietsema

Ship drawing (diptych) 2009

Ink on paper

129 × 356 cm

© Paul Sietsema, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

LA-based Paul Sietsema’s drawings and films reveal a forensic interest in both the materiality of the objects he shows and the media he uses to portray them – alongside a concern for the legacies of past episodes of art history and their artefacts. The photo-perfect quality of his drawings offers a visual fascination that demands intense study. This is particularly seen in his diptych ink drawings of sea vessels, Ship drawing and Boat drawing, both 2010, which each faithfully reproduces both sides of a photographic image, including every dent, rip and aged yellow mark. He describes his desire ‘to extend the possibilities of the medium whilst forcing the medium itself to become more apparent’, often using film as another means by which the representation of an object can be both material and image. For Sietsema, the hours spent building up the drawing layer after layer reflects the layers of its history:

So it’s a boat captured in the ocean, captured in a photograph, the photograph captured in photographic paper, and the photographic paper captured in the paper of the drawing… I like the way the antiquated layers intersect with the antiquated image of sea travel. On the boat, one of the figures is waving – perhaps in farewell to photography.

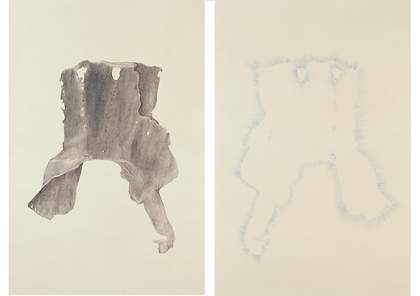

Trisha Donnelly

Untitled (diptych) 2004

Ink on paper

42× 29.7cm each

© Trisha Donnelly, courtesy Casey Kaplan Gallery, New York

Fellow West Coast artist Trisha Donnelly (who, like Celmins, now lives in New York) suggests her drawings, as well as sculptures, photographs and films, have a live charge that extends the viewer’s experience of her work beyond mere looking. She often adds an aural component or mystical narrative – if we are willing to suspend our disbelief. Curator Laura Hoptman describes her drawings as ‘portals’, and Donnelly assigns to them almost talisman-like properties, describing making them as being like a mechanical task assigned to her. ‘Drawings can be a more intense version of presence I think. They can act as actions. They are worse. More horrible. More distant.’ For example, the artist claims that the first part of Untitled (diptych) 200), a drawing depicting what could be a solidified mass of space or an indecipherable organic form, has penetrated the gallery wall on which it is hung, resulting in a second more ethereal, inverse version of the same image to appear of its own accord on the other side. The investment in the material nature of drawing, in particular using graphite on paper, in the work of these artists is not a nostalgic return to modernist notions of ‘truth to materials’, as it is tempered by a multidisciplinary approach and an adherence to an intellectual pursuit of how images carry meaning. The palpable physical presence and visually active surfaces of Lucy Skaer’s enormous black drawings also ‘prolong and interrogate the act of looking’, not least because their scale means it is impossible for the eye to take in the image as a whole. In drawings such as Death 2006, she constructs an image from tiny patterning in graphite or black marker pen, using grey and black spirals to both depict and disrupt her pictorial motif, in this case that of a whale skeleton. She is interested in disturbing and making irrational the traditional act of representation, by creating drawings that in their disorientating size and material density demand the same physical presence as sculpture.

Anna Barriball

Untitled

Installation view at MK Gallery, 2011

Marker pen on windbreaks, metal poles

© Anne Barriball, courtesy MK Gallery, Milton Keynes

Another five-metre-wide drawing titled The Deluge 2008 takes as its starting point Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing, Deluge with rocks, floods and a tree c.1516, but abstracts the image in a systematic matrix of dense patterning. The experience of looking at this work constantly shifts between the macro scale of the object and the micro detail of the mark, which optically intrigues and at times overwhelms the viewer in its intensity. Anna Barriball’s works, such as Untitled 2009, bring together the parallel practices of sculpture and drawing to create pieces that sit somewhere between a flat image and a three-dimensional object. Created through the simple act of rubbing her pencil on paper across an object selected from her everyday environment, a work such as Brick Wall 2005 emphasises both the physical substance of the original subject and its subsequent representation as an image. The metallic graphite sheen of the drawn surface gives the piece a visual density, an opacity that prolongs the act of recognition. Like the works of all the artists discussed here, some of Barriball’s drawings require a huge amount of time and labour to execute, although other pieces result from instant, ephemeral acts of production.

While process itself does not motivate or interest Barriball or the others, the time invested perhaps lengthens the pace at which the viewer encounters the work. As Musgrave comments on his own drawings: ‘All those irrecoverable hours seem to me to hover in a ghostly way around the work… I hope this slows down the rate at which it’s possible to digest the work.’