Editors’ note

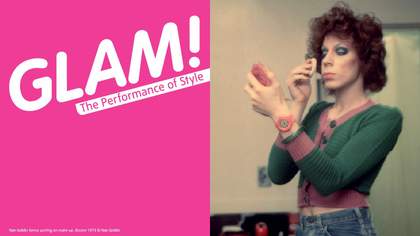

Over a few months in 1972 three songs appeared that would define a new era: T Rex’s Metal Guru, David Bowie’s Starman and Roxy Music’s Virginia Plain. Their self-conscious yet confident and poised style that became collectively known as Glam rock (though some hated this label) erupted from the hippy generation that preceded it. As Jon Savage writes, they ‘crashed the barriers between high and low culture, fine art and street style’. The key characters of this period in art, music and film from both Europe and the USA appear in Tate Liverpool’s Glam! The Performance of Style, the first exhibition of its kind on this subject.

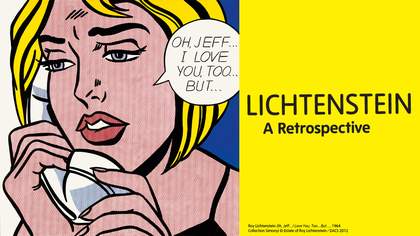

A decade earlier there was a different kind of watershed moment, when American Pop art fully entered the minds of British artists. For Allen Jones, his ‘creative imagination was set free’ after seeing reproductions (in black and white) of Roy Lichtenstein’s work in 1962. He recalls the ‘culture shock’ that liberated his generation of artists (including fellow Europeans, as John-Paul Stonard explores), to explore ‘a new pictorial language consonant with our times’. These early works and many others will be on view in Tate Modern’s Lichtenstein retrospective.

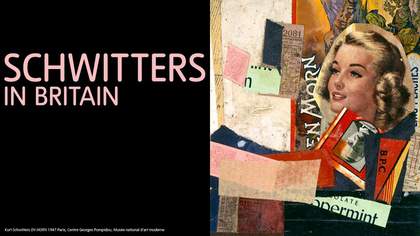

One wonders if the residents of the Lake District would have experienced a comparative sense of revelation (or perhaps bafflement) on entering Kurt Schwitters’s Merz barn, the third of his Merzbau constructions, unfinished at the time of his death in 1948. Paul Farley, in his evocative celebration of the artist’s final decade spent in England, to coincide with Tate Britain’s ground-breaking exhibition Schwitters in Britain, likens entering the ruins of the barn to ‘coming across the image of a semiconductor on a cave wall’. Schwitters cast a long and influential shadow over the decades that followed. As Farley notes, there is a whole history of his impact on British culture, from the art school bands of the 1960s and 1970s to the look of Punk packaging. And the 1980s were ‘pure Schwitters, a sound collage’.

The German’s legacy continues across the globe. In Melanie Smith’s video work Xilitla (which entered Tate’s collection last year and is now on display), she subtly interweaves part of Schwitters’s Ursonate into her Mexican narrative, while Adam Chodzko and Laure Prouvost present two new commissioned works inspired by Schwitters which you can see in the Tate show.

Bice Curiger and Simon Grant