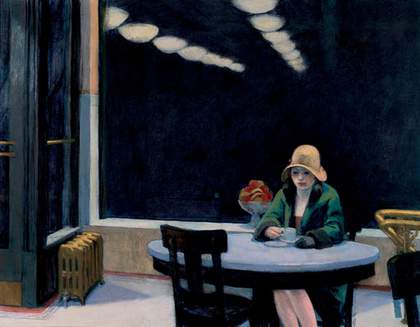

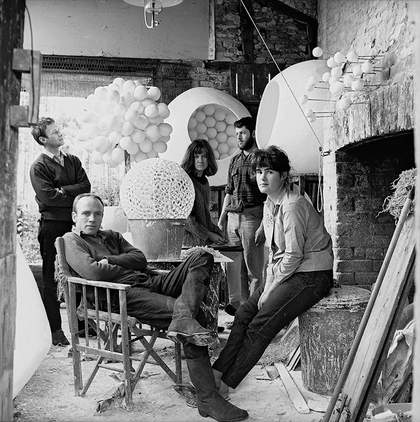

Patrick Caulfield and friends photographed by Peter Ward in 1961

© Peter Ward; courtesy Peter Ward

Patrick Caulfield (1936–2005) is known for his vibrant paintings of modern life that reinvigorated traditional artistic genres such as the still life. His work came to prominence in the mid-1960s after studying at the Royal College of Art, where fellow students included David Hockney. Through his participation in The New Generation exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1964, he became associated with Pop Art – a label he resisted throughout his career. Caulfield preferred to see himself as a ‘formal artist’ and an inheritor of European painting traditions from modern masters such as Georges Braque, Juan Gris and Fernand Léger, who influenced his composition and choice of subject matter.

The 1960s was a period of radical and far-reaching change in Western culture, perhaps the key historical turning point of the twentieth century. London’s skyline was transformed by new buildings such as the Hilton on Park Lane and the South Bank Centre and Millbank Tower on the Thames. While the government continued to stimulate commercial redevelopment, art was considered to be a vital part of social change. Film, television and magazines created an interest in the wider world as well as serving as a showcase for consumer goods, and by 1960 transatlantic air travel was no longer the preserve of the elite, opening up new horizons to all. The turn of the decade was characterised by optimism that corresponded to increased affluence, but also to altering concepts of class, taste and status, and to new forms of social aspiration in Britain. A new generation of artists that included Caulfield developed ways of dealing with modernity in their work that was radically innovative. Their engagement with the world secured an unprecedented position for art, and for many of the artists themselves, in the eyes of the public.

Prior to taking up his place as a student at the Royal College of Art, Caulfield spent the summer of 1960 travelling in Europe. With seven fellow students, including Pauline Boty, he went by train to Greece, later hitch-hiking his way back to London through Italy and France. It was his first trip abroad. He collected postcards including pictures of Minoan frescos because he ‘liked the simplicity and directness’ of the images. At the time he didn’t realise that the black lines had been added by the printer, ‘but these cards struck me as being very amusing and quite strong imagery. So I thought about using lines around my own work’. Caulfield appreciated their exotic, decorative qualities, which were to inspire the composition of early works such as Still Life with Dagger 1963, where the Mughal (Indian) dagger with a horse’s head and scabbard were drawn in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Still Life with Necklace 1964 – a complex arrangement of Turkish pots, jewelled knives and a necklace patterned with a filigree of fine lines set against a stark, geometric background.

Patrick Caulfield

Still Life with Dagger 1963

Oil on board, 121.5 x 122 cm

© Estate of Patrick Caulfield, all rights reserved, DACS 2013, Tate Collection

Both of these works are characteristic of Caulfield’s approach to painting in the 1960s. Early on in his career he rejected gestural brush strokes for the more anonymous technique of signwriter and developed his own flat description of three-dimensional form. In the two paintings, images of objects are paired with angular geometric shapes, isolated against vivid areas of flat colour, which highlight his use of gloss paint on board and his hard, linear technique. They make direct reference to the still lifes of the Cubist painter Juan Gris, who was to prove so influential to him. Caulfield’s admiration for Gris’s work gave him the excuse to paint Portrait of Juan Gris 1963, one of the very few images of a figure he made. As he explained:

What I like about Juan Gris’s work is not that he’s dealing with different viewpoints, it’s the way he does it. It’s very strong, formally, and decorative.

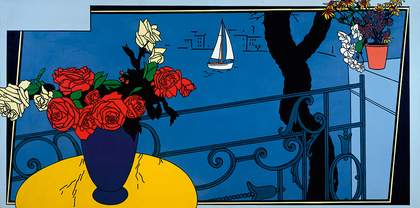

While Caulfield’s imagery is rooted in daily experience or in images that are equally familiar through postcards, French recipe cards, advertisements or travel brochures, they are often underpinned by a sense of the exotic. This is reflected in a work such as Santa Margherita Ligure 1964 with its picture-postcard prettiness. It is the first of many paintings based on a Mediterranean theme, and in the context of his experience of the austere post-war world, the artist’s fascination with this seems an understandable response.

The terms ‘exotic’ or ‘exoticism’ are today often treated as synonymous with orientalism and other colonialising discourses, perhaps best exemplified by the Great Exhibition of 1851, where artefacts of the British Empire were displayed as a spectacle for the crowds. In contrast, the Festival of Britain, which took place in 1951 when Caulfield was a teenager growing up in Acton, west London, celebrated the country’s recovery after the Second World War. Billed as ‘a tonic for the nation’, it was a showcase of Britain’s finest architecture, design, fashion, science, arts, manufacturing and creative industries. Everyday life was still drab and grey, with many things continuing to be rationed: the everyday exotic was just out of reach for the majority. The festival aimed to convince everyone that they were entering the age of modernity. While it took pride in Britain’s past, most of the exhibits looked to the future, and science and technology featured strongly. Indeed, in one of the pavilions many Londoners saw their first ever television pictures. Thus, at this time the modern could be seen to be both exotic and everyday. The sense of the exotic in Britain in the post-war period was not so much an exoticism of the tropics, of oriental luxury and distant horizons, but rather a rediscovery of a European and American otherness, exotic yet within easy reach, well-illustrated by the impact of cookery writer Elizabeth David’s A Book of Mediterranean Food 1950, with its cover designed by John Minton, which is typical of a particular sense of the exotic that Caulfield was to react to.

Patrick Caulfield

Santa Margherita Ligure 1964

Oil on board, 122 x 244 cm

© Estate of Patrick Caulfield, all rights reserved, DACS 2013, courtesy The Bridgeman Art Library, private collection

French recipe postcard used as source material for Santa Margherita Ligure 1964

However, as the art historian Anne Seymour wrote in 1969, Caulfield ‘never felt the romantic interest in America which affected so many artists’. He had less of a celebratory attitude to the modern world, even though he was fascinated by style. His subject matter can also be understood as being grounded in European culture and the tradition of still life painting. He was interested in art history and how images are used to construct a visual language. For example, much of the source material for his paintings follows that of the Cubist still life, which deals principally with the café. And yet, in the whirl of new experiences and their mediation by mass media, Caulfield remained distanced.

This distance was not just playful but a melancholy, romantic irony, perhaps best highlighted by his architectural pictures and interiors of the 1970s and 1980s that directly engage with the contemporary social landscape and the representation of modern life. There is a recurrence of images of drinking and eating in bar and restaurant interiors which have a sense of the new, post-war world, tinged with an abiding melancholy. As Caulfield wrote in 1970: ‘The subjects are imaginary, so that they are particular yet stereotyped images.’ In After Lunch 1975 the scene takes place in the afternoon when the lights have been turned off and a waiter surveys the empty restaurant. The variation of tone contributes to the atmosphere by suggesting a shadow thrown across the imaginary space that is reminiscent of Edward Hopper’s treatment of light and shade and the frozen time quality of his interiors – an artist he also greatly admired.

Caulfield’s ability to animate interior spaces, to elicit an atmosphere, or to suggest a sense of place shot through with emotional resonance is present in the majority of his work. With extreme subtlety and finesse, he explored paradoxes of presence and absence, transience and permanence and the uncanny mix of pleasure and unease encountered in modern life. The character of contemporary living is captured in the paintings Foyer 1973 and Café Interior: Afternoon 1973, both of which focus on the subject of the interior, updated and reconfigured in Caulfield’s trademark style, and in Springtime: Face a la Mer 1974, which like the earlier Santa Margherita Ligure contains suggestions of continental holidays. Likewise, Dining Recess 1972 takes its imagery from books on interior design published in the 1960s. The entire work is in sombre grey except for the blue of the sky seen through a high window and the perfect sphere of a globe lamp in pale yellow positioned directly above Tulip chairs and table designed by Eero Saarinen. Elsewhere, Dining/Kitchen/Living 1980 highlights Caulfield’s experimentation with pictorial language where he inserts an element of trompe l’œil – in this instance his family’s casserole – to contrast with the rest of the picture. This combination of styles and subject matter (a key feature of his work of the mid-1970s and 1980s) mixes high art and low or kitsch art with a cool eye that refuses to either valorise or denigrate one element or the other. The lovingly detailed advertisement-style rendering of a chicken kiev or a bowl of mussels, the carefully reproduced William Morris wallpaper, the fondue dish, or office paraphernalia all reflect his interest in the mundane and the ordinary. There is no snobbishness in his choice. Just as in an early painting Sculpture in a Landscape 1966, which depicts a Barbara Hepworth-like sculpture placed in an anonymous landscape, a sense of irony towards the topic is often tempered by a sense of humour and affection. He neither uncritically champions popular culture as did some of his contemporaries, nor retreats to a high art position that could not truly represent the contemporary world. Caulfield thus remains true to his vocation as a painter of modern life; his pictures refuse judgment by revealing a concern with the everyday that makes visible its enigmatic core.