I first saw a picture of David Smith’s Wagon II in the mid 1960s. At the time I was working as Henry Moore’s assistant, so I was drawn to Smith’s absurdly heroic looking piece as a talisman against the English pastoralism of the time.

I went to Bolton Landing – Smith’s studio, near Lake George in upstate New York – in April 1975. Even though he had died almost ten years previously, I had the strong sense of being allowed into someone else’s life. There was an American ‘can-do’ pioneer-meets-inventor feel about the place. There were a lot of his sculptures and offcuts lying around, covered in snow, which looked like the bits of material that you would find in any blacksmith’s yard. I liked the matter-of-factness of them. Against the snow they showed the sense of calligraphy in the landscape – definitive David Smith; not really an indoors sort of sculpture. I was living in New York (which had just gone bankrupt) and had just discovered Walker Evans’s photographs – someone who also has a magnificent sense of the calligraphic object. At the time I was making things from what I had bought or found on Canal Street; things that were intentionally tentative, that looked as if they would fall apart. I have never really been drawn to material uniformity in sculpture, but I share Smith’s sense of the provisional. The trouble is, once you weld something that precarious feeling gets frozen solid.

On the streets boys used to make those bricolaged box cars. Smith, though, is a bigger boy, and I like the fact that Wagon II was made from an assemblage of huge discarded steel forgings which he brought back from Italy after the time he spent making sculptures in Spoleto. How did he do it? What kind of suitcase did he have? I bring back all sorts of stuff too, from the orphaned objects of the Caledonian Road in North London to Moroccan street sweepings, but never on his scale. And the result makes the work feel very inevitable. I look at it and think: ‘Oh yes, they’ve always made hundreds of those.’ We already know what it is, we have seen it before – but it took him to make it to allow us to find that out.

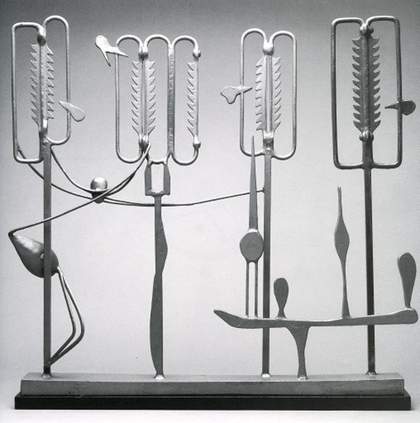

Smith, like Picasso, understood his materials and how they behaved. When you look at Picasso’s sculpture, you feel that the components are very honourably themselves – the bread basket, a toy car, a bicycle seat and handlebars. They all hold together. And Smith clearly knew all that language very well. There is a good pace and balance in the composition in Wagon II. It is like reading a well-formed sentence. For example, the central upright of the sculpture is like a haiku. The form has a rather Matisse-like shape: two curves and a counter curve. But running right through the whole thing is a vertical, nearly straight line. And that’s what holds it there and stops it feeling like it’s going to fall over. But we all know that to stop it falling over it’s got a great big forest of welding at the bottom.

There is one excessively big wheel, much bigger than its three siblings. On the inner face he welded that rectangular plate – perhaps originally a technical thing, but its shape is typically Smith making that circle feel much more like a circle. It resembles a Suprematist drawing.

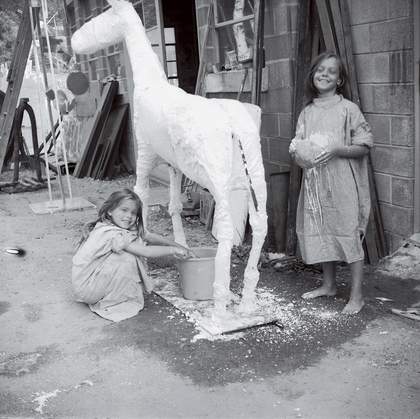

You can see from Wagon II that he’s obviously gone through a lot to get to that stage. You can see him struggling, and troubling over the process. Smith wanted his work to be argumentative, and here is a piece that comes with a noise of its own making in a really physical way. You can hear the grinding. You can hear the welding. And you can hear the blows of the hammer. (My ideal sculpture exhibition would let you see the process of making the works – one in which you could watch their birth into the world. You get as much of that in Barry Flanagan’s Baby Elephant as in Robert Smithson’s Asphalt Rundown.)

Smith was definitely in a romantic relationship with the rawness of American ‘stuff’. He had a sense of wonder about the beefiness of US manufacturing and industrial product. He was the sort of person that was drawn to great chunks of metal from foundries – scraps from the heavy end of engineering. That is how he saw his culture, and Wagon II comes out of that. (His approach is miles away from what I do. I have never worked with hot forged steel.) But there is tenderness in his work too. People think of welding as being a bit blokey, but there’s something very gentle about the way he brings the details of the sculpture into play. On the outer surface of the large wheel he has inscribed the words ‘Hi Candida’, a message to one of his daughters, along with the date, April 16th 1964, when it was made.

Seeing Wagon II in Tate Modern is a very different experience from being at Bolton Landing. The chocolate-brown patina on it is beginning to feel toffeeish. I don’t think Smith would have approved of that – it starts to look like art. And it would be good to skew it, so that it doesn’t sit so obediently parallel to the walls. It shouldn’t be garaged. It would also be great to see it in another room, rather than alongside Rothko, Krasner and Pollock, as you can’t pigeonhole Smith as an Abstract Expressionist artist.

I remember someone writing about Smith’s work saying that people took exception to his contemporary Robert Motherwell because he read Cahiers d’Art in French, whereas Smith just looked at the pictures. So Smith’s vision of European art was seen through crappy reproductions. There is an endearing innocence to that – a bit like mishearing someone’s words down a bad telephone line. Culture is always about Chinese whispers, full of poor translations. I like the possibility for misinterpretation. It means that, however well ‘designed’ his work, and however ugly it might look, or how clunky some of the joins are, it is never, unlike, say, a Robert Morris sculpture, too stylish.