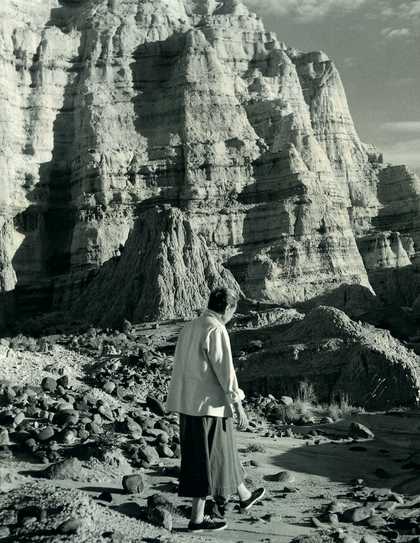

Georgia O’Keeffe walking at the White Place, New Mexico, 1957, photographed by Todd Webb

© Estate of Todd Webb, Portland, Maine, USA

‘It takes a kind of nerve… and a lot of hard, hard work.’ So said Georgia O’Keeffe at the age of 90 when asked for an explanation of her success. From an early age O’Keeffe had decided that she wasn’t going to spend her life, as she put it, ‘doing what had already been done’. And it worked. She has become one of the best-loved American artists of the 20th century. From her radical debut in 1916 to her late landscapes inspired by her international travels, she produced works for more than 70 years that oscillated between figuration and abstraction.

Born the second of seven children, Georgia Totto O’Keeffe grew up on a farm near Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, and studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League of New York. Her style and thinking shifted dramatically in 1912 when she studied the revolutionary ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow, whose focus on design and composition opened up new avenues for her art. This led to a series of abstract charcoal drawings in 1915 that represented a major break with tradition and made O’Keeffe one of the very first American artists to explore abstraction, even if her work was rooted in observed landscape. These drawings were shown to art dealer, photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, who was the first to exhibit her work in 1916. (He later became her husband.)

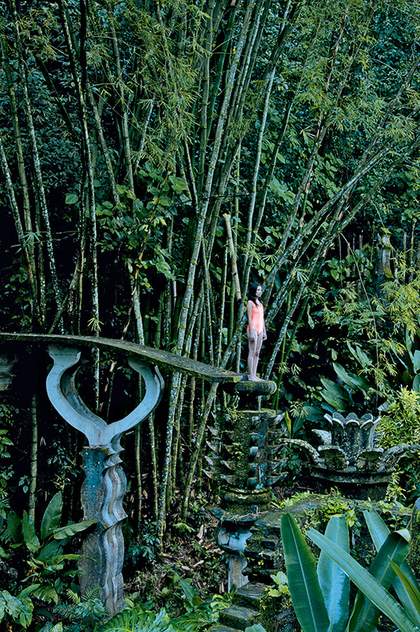

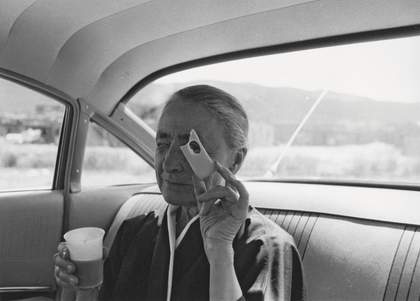

Tony Vaccaro, Georgia O’Keeffe, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico 1960, gelatin silver print on paper, 16.7 x 23.5 cm

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA; photo courtesy Michael A. Vaccaro Studios

In the summer of 1929 O’Keeffe made the first of many trips to northern New Mexico. The tough, dry landscape and its particular regional style of adobe architecture and indigenous art inspired another new direction. Bones, empty landscapes, wooden crosses, the sky, her studio door – all became her subject matter to which she would repeatedly return.

Over the next 20 years she spent part of most years living and working in New Mexico (first at Ghost Ranch and then Abiquiu), making it her permanent home in 1949, three years after Stieglitz’s death. In the 1950s O’Keeffe started to travel across the globe, and would subsequently make paintings that evoked some of the many places she visited, including parts of the Middle East, Asia and Latin America. During her later years she would continue introducing new subjects, most notably her series of cloud paintings. A degenerative eye condition slowed down her activity, and she completed her last oil painting without the help of a studio assistant in 1972. She died in Santa Fe on 6 March 1986, aged 98.

O’Keeffe became an important figure for female artists, particularly during the 1970s, and her influence continues today.

Georgia O’Keeffe in her own words

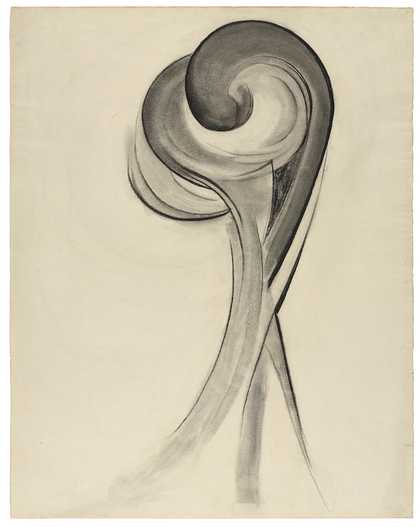

Georgia O’Keeffe, No.12 Special 1916, charcoal on paper, 61 x 48.3 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, photo © 2015 Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

I decided I was going to begin to make drawings. I thought, well, I have a few things in my head that I never thought of putting down, that nobody else taught me, and I was going to begin with charcoal, and I wasn’t going to use any colour until I couldn’t do what I wanted to do with the charcoal or black paint.1

Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue I 1916, watercolour on paper, 78.4 x 56.5 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, photo © 2007 Christie’s Images Limited

I was busy in the daytime and I made most of these drawings at night. I sat on the floor and worked against the closet door. Eyes can see shapes. It’s as if my mind creates shapes that I don’t know about. I get this shape in my head and sometimes I know what it comes from and sometimes I don’t. And I think with myself that there are a few shapes that I have repeated a number of times during my life and I haven’t known I was repeating them until after I had done it.1

Georgia O’Keeffe, Sunrise, 1916, watercolour on paper, 22.5 x 30.2 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Barney Ebsworth collection

The Texas country that I know is the plains. It was land like the ocean all the way around. Hardly anybody liked it, but I loved it. The wind blew too hard, the dust flew, and we had heavy dust storms. I’ve come in many times when I’d be the colour of the road. At night you could drive away from the town, right out into space. You didn’t have to drive on the road, and when the sunset was gone, you turned around and went back, lighted by the light of the town.1

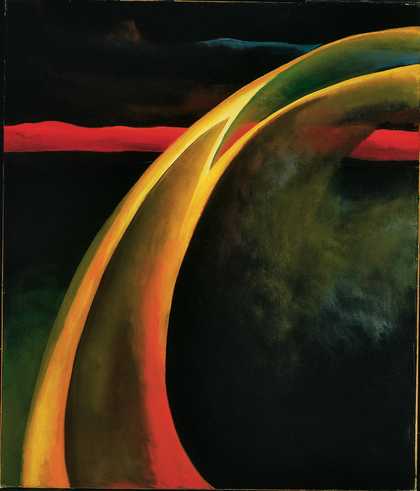

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red and Orange Streak 1919, oil on canvas, 68.6 x 58.4 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe for the Alfred Stieglitz Collection

All the earth colours of the painter’s palette are out there in the many miles of bad lands. The light Naples yellow through the ochres – orange and red and purple earth – even the soft earth greens.2

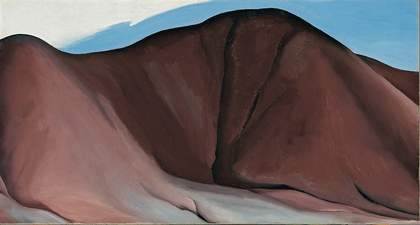

Georgia O’Keeffe, Rust Red Hills 1930, oil on canvas, 40.6 x 76.2 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Brauer Museum of Art, Valparaiso University

When I got to New Mexico, that was mine. As soon as I saw it, that was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me exactly. It’s something that’s in the air, it’s just different. The sky is different, the stars are different, the wind is different.1

I feel at home here – I feel quiet – my skin feels close to the earth when I walk out into the red hills…3

Georgia O’Keeffe, Purple Hills 1935, oil on canvas, 40.6 x 76.2 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy San Diego Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Norton S. Walbridge, 1976

I seemed to be hunting for something of myself out there, something in myself that will give me a symbol for all this, a symbol for the sense of life I get out here.4

I used to get right up in the morning and start out and stay out all day. I’d start off around seven and not get back till around five. It was terribly hot and in the afternoon about four o’clock, the bees would try to get into the car, so you’d have to close the windows. It was hot. The Model A was wonderful. You could take the back seat out. I could sit on the driver’s seat when I turned it around to work on the back seat. And the windows were large enough so it was very good. I could use a great big canvas…1

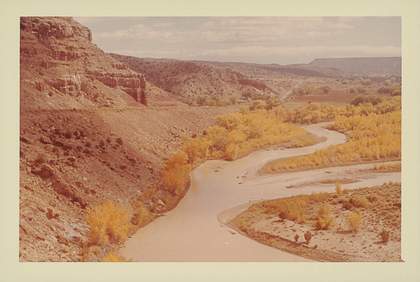

Photograph of the Chama River, New Mexico, taken by Georgia O’Keeffe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016

The Black Place is about one hundred and fifty miles from Ghost Ranch and as you come to it over a hill, it looks like a mile of elephants – grey hills all about the same size with almost white sand at their feet. When you get into the hills you find that all the surfaces are evenly crackled so walking and climbing are easy…

I don’t remember what I painted on my first trip over there. I have gone so many times. I always went prepared to camp. There was a fine little spot quite far off the road with thick old cedar trees with handsome trunks – not very tall but making good spots of shade…

Such a beautiful, untouched lonely-feeling place – part of what I call the Far Away.5

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Place Green 1949, oil on canvas, 94.6 x 117.5 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, collection of Jane Lombard

The first year I was out here I began picking up bones because there were no flowers. I wanted to take something home, something to work on… When it was time to go home I felt as if I hadn’t even started on the country and I wondered what I could take home that I could continue what I felt about the country and I couldn’t think of anything to take home but a barrel of bones. So when I got home with my barrel of bones to Lake George I stayed up there quite a while that fall and painted them. That’s where I painted my first skulls, from this barrel of bones.1

Georgia O’Keeffe, Pelvis Series 1947, oil on canvas, 101.6 x 121.9 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Eykyn Maclean

The bones seem to cut sharply to the centre of something that is keenly alive on the desert even though it is vast and empty and untouchable – and knows no kindness with all its beauty.6

I was the sort of child that ate around the raisin on the cookie and ate around the hole in the doughnut saving either the raisin or the hole for the last and best. So probably – not having changed much – when I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes in the bones – what I saw through them – particularly the blue from holding them up in the sun against the sky as one is apt to do when one seems to have more sky than earth in one’s world… They were most wonderful against the Blue – that Blue that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.5

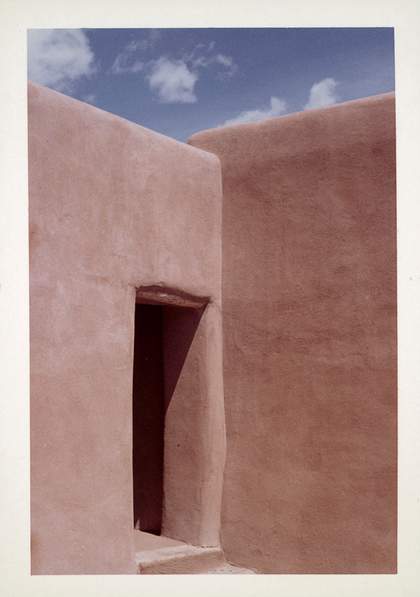

Photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Abiquiu house, New Mexico

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, gift of the Barnett Foundation

When I first saw the Abiquiu house it was a ruin with an adobe wall around the garden broken in a couple of places by falling trees. As I climbed and walked about in the ruin I found a patio with a very pretty well house and bucket to draw up water. It was a good- sized patio with a long wall with a door on one side. That wall with a door in it was something I had to have. It took me ten years to get – three more years to fix the house so I could live in it – and after that the wall with a door was painted many times.5

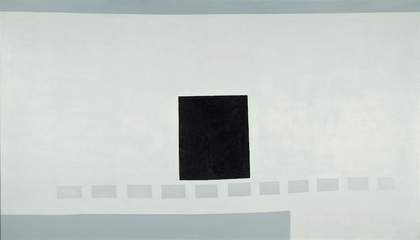

Georgia O’Keeffe, My Last Door 1952–4, oil on canvas, 122.5 x 213.8 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, gift of the Barnett Foundation

Those little squares in the door paintings are tiles in front of the door; they’re really there, so you see the painting is not abstract. It’s quite realistic. I’m always trying to paint that door – I never quite get it… It’s a curse – the way I feel I must continually go on with that door. Once I had the idea of making the door larger and the picture smaller, but then the wall, the whole surface of that wonderful wall, would have been lost.7

I would rather come here than any place I know. It is a way of life for me to live very comfortably at the tail end of the earth so far away that hardly anyone will ever come to see me and I like it.8

The unexplainable thing in nature that makes me feel the world is big far beyond my understanding – to understand maybe by trying to put it into form. To find the feeling of infinity on the horizon line or just over the next hill.5