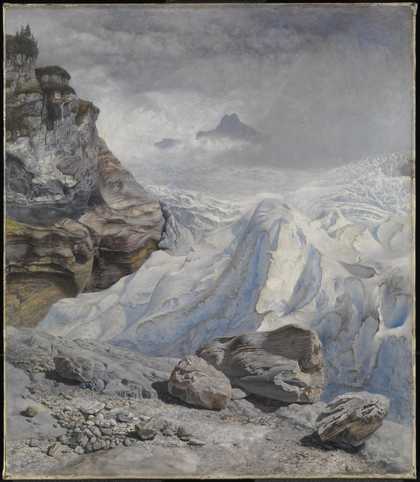

John Brett

Glacier of Rosenlaui (1856)

Tate

In 1884, the influential artist and critic, John Ruskin, gave a lecture in which he sounded the alarm about the cost of England’s rapid industrialisation. There was ‘something wrong with the sky’, he said. In all his years of observing the natural world (faithfully recorded in 50 years of sketchbooks and diaries), he had never seen anything like it. He went on to describe what he called ‘The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century’:

It looks partly as if it were made of poisonous smoke; very possibly it may be: there are at least two hundred furnace chimneys in a square of two miles on every side of me. But mere smoke would not blow to and fro in that wild way ... By the plague-wind every breath of air you draw is polluted, half round the world.

His talk was greeted with derision at the time. One wag went as far as to deem it a ‘jeremiad on modern clouds’. And yet, in this present era of increasingly violent weather, Ruskin’s warning has come to seem remarkably prescient. There are atmospheric consequences to our actions. We watch the sky uneasily, just as he did.

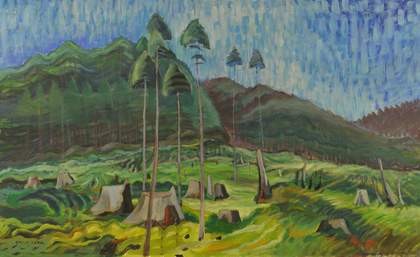

Emily Carr

Odds and Ends 1939, oil paint on canvas, 67.4 × 109.5 cm

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

The price of progress was a theme that made its way across the Atlantic as well. Artists such as Thomas Cole, a founder of the Hudson River School, set out to capture the promise of America’s seemingly inexhaustible wilderness in his paintings. In early works, such as Sunrise in the Catskills 1826, Cole sought to follow Ruskin’s injunction to ‘study nature carefully and reproduce her wonders accurately’, but, before long, the forests he painted were logged as industry and tourism expanded into the Catskills. In his five-part series, The Course of Empire 1833–6, Cole allegorically depicts the hubris of mankind’s attempts to tame nature. The paintings begin with a vision of untouched wilderness that becomes a cultivated countryside, which is transformed, in turn, to a gleaming cityscape, then a land ravaged by war. The final work in the series shows the ruins of the city overtaken by green again, an alluringly peaceful sight after all the human drama that has come before it.

This search for transcendence, shot through with moments of dread, appears again in the work of the Canadian artist, Emily Carr, who took as her lifelong subject the majestic forests of British Columbia. In her dull early paintings, there is a dutiful attention to detail that seems to hammer out any of the landscape’s depths. But her mature work is startlingly alive and strange. In her travels, she had come across the totem poles and dwellings of the land’s indigenous people, and, influenced by their intricate handiwork, her painting style evolved into more mysterious, mystical territory. The solitary trees seen in Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky 1935 and Odds and Ends 1939 are made ghostly by the implied presence of their vanished forests.

Sir Henry Rushbury

The Forest of Brotonne (1920)

Tate

The notes Carr made just before she began this work attest to a dark memory of violence that belies the tenderness of her painting:

There’s a torn and splintered ridge across the stumps I call the ‘screamers’. These are the unsawn last bits, the cry of the tree’s heart, wrenching and tearing apart just before she gives that sway and the dreadful groan of falling, that dreadful pause while her executioners step back with their saws and axes resting and watch. It’s a horrible sight to see a tree felled, even now, though the stumps are grey and rotting. As you pass among them you see their screamers sticking up out of their own tombstones, as it were. They are their own tombstones and their own mourners.

Ruskin, Cole and Carr all found themselves uncomfortably ahead of their time in their understanding of the damage caused by industrial societies, but, as the scope of destruction grew, a few visionary artists heeded their call for radical new ways of thinking and living.

Agnes Denes stands in Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan 1982

© Agnes Denes, courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York, photo: John McGrail

In 1959, the German artist, Gustav Metzger, wrote a manifesto announcing the need for ‘auto-destructive’ art: things expressly built not to last, featuring materials that were easily damaged or destroyed. This planned obsolescence would make them a suitable public monument for what Metzger called ‘the obscene present’ of a world threatened by nuclear war and environmental degradation. The artist demonstrated how this might work by setting up sheets of nylon in Central London, then throwing acid over them. In less than half an hour, they had disintegrated completely. ‘The important thing about burning a hole in that sheet was that it opened up a new view across the Thames’, Metzger later said. He soon turned to less abstract demonstrations of how man-made things obstruct and harm nature. In 1970, he had a customised car, Mobbile, drive through London and Vienna. On its roof was a transparent box filled with plants, which the car’s exhaust pipe was funneled directly into. As the car moved through the city, the plants were asphyxiated by the fumes.

Gustav Metzger’s Mobbile on the streets of Vienna, 1970

© Estate of Gustav Metzger. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020

Not long before this, Joseph Beuys, another ecologically minded prophet, began to create a shapeshifting body of work that ranged from performance art and installation pieces to a community-based art he deemed ‘social sculpture’. One of his first entanglements with nature was his piece called How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, performed for the first time in 1965. For this, he sat behind the window of a locked gallery, his face covered in honey and gold leaf, tenderly holding and speaking to the carcass of a hare, as if it might be resurrected by this act of radical attention. He went on to practice other examples of what the critic Suzi Gablik has called ‘connective aesthetics’, most famously in his piece 7000 Oaks, which proposed the planting of said trees around the city of Kassel, Germany. Beuys began this project in 1982 in the hope that it would spark widespread environmental awareness and change.

Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Oaks on the lawn in front of the Fridericianum in Kassel for Documenta 7, 1982

© DACS 2020

That same year, the Hungarian-born artist, Agnes Denes, launched an ambitious project called Wheatfield – A Confrontation, which also engaged with the possibilities of art as a reparative process. The work entailed repurposing a Battery Park landfill in Manhattan as an improvised farm. Denes and her collaborators planted an acre and a half of wheat there, and the subsequent exhibition featured an iconic picture of the artist walking through the field of wheat, the World Trade Center behind her. The bucolic image effaced the enormous labour that had gone into creating the field on such unwelcoming land. Denes claimed she had to beg her helpers again and again to come back, and was able to pay them only in sandwiches. The vision of the piece was to represent ‘food, energy, commerce, world trade, economics ... mismanagement and world hunger’, she said. Despite the loftiness of these ideas, the artist took care to include meticulously catalogued photographs of the insects that had made their home in the new field.

This focus on both the macro and micro elements of our world has proven a potent example of environmental engagement in this time of ecological anxiety. One of the enduring difficulties of addressing the current climate emergency, and its attendant losses, is that the vastness and complexity of the affected systems overwhelm our usual ways of registering and responding to danger. Contemporary artists such as Olafur Eliasson, Gabriel Orozco, Pinar Yoldas, Jerry Buhari, Aviva Rahmani and Margaret and Christine Wertheim are continuing the difficult work that John Ruskin began when he unveiled his apocalyptic observations to a skeptical audience. The power of these artists’ work lies in their ability to make visible the damage our species has done. Only then can we imagine the possibility of repair.

Jenny Offill is a novelist whose latest book is Weather, published by Granta.