Editor's Note

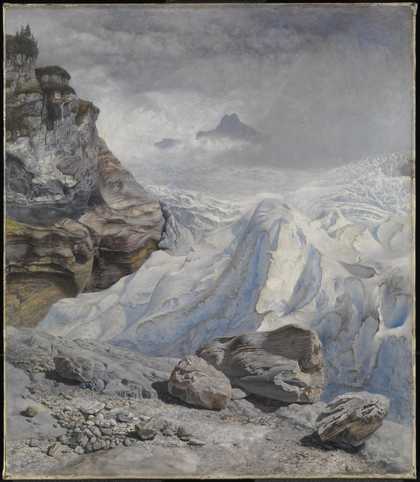

John Brett

The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs (1871)

Tate

I usually compose this editorial amid the busy throng of the Tate offices, but for this special issue, which takes the many treasures of the Tate Collection as its starting point, I am writing amid the sounds of my children playing and the chat of neighbours exchanging stories. If we have learnt anything from this global crisis, it is that we should value, with even greater focus, those we have around us.

I’m sure you’ll agree that this is nowhere more apparent than in the extraordinary demonstrations of kindness, bravery, support and community spirit found in all corners of society – from the smallest gesture to the tireless commitment of so many who are helping others.

With this in mind, we ask, what active role can art institutions such as Tate play? Is there a beneficial direction that museums can take, in order to connect ever more closely with their audiences – not only further developing the rich histories of our shared collections but also regarding them as places of care: of communities, audiences, artists and staff?

As a resident living locally to Tate Modern, Ismail Einashe has already experienced first-hand, through his participation with Tate Exchange, how an art institution can offer one kind of accessible model for fruitful, inclusive, collective approaches – through conversation, participation and collaboration with diverse groups.

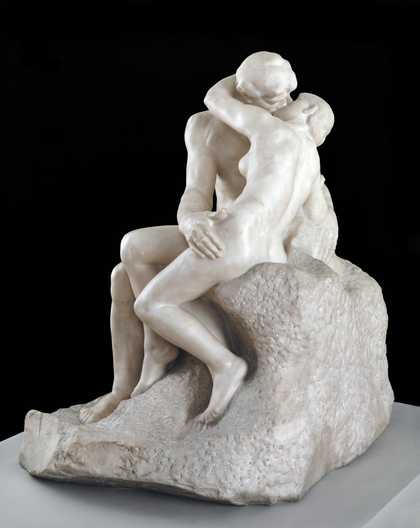

Of course, the transformative, and sometimes healing, power of art also takes place during our own intimate engagement with artworks, whether we experience them close up or on printed pages such as this – from the calming image of gardens in bloom created by artists who were deeply attached to their own spaces, to artworks inspired by love and devotion. While some artworks might offer pure visual escape into other worlds, they can also provide a portal to another way of thinking or feeling about ourselves and those around us.

You can find many examples of such works inside this issue, including our cover image, which features a detail from John Brett’s painting The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs, made after he sailed around the South West coast of Britain. When Brett first exhibited the work in 1871, several months after he finished it, the picture was roundly criticised for being too sparkly and unrealistic.

However, seen through today’s eyes, and during these times, it feels like a powerful image of hope, optimism and resilience, reflecting the spirit of the individuals and communities whom we have witnessed coming together. With this sentiment in mind, we hope that you enjoy this issue, and we look forward to welcoming you back into the galleries soon.