Monty Don in Longmeadow, his garden in Herefordshire

Photo © Marsha Arnold

SIMON GRANT How did you first get involved with gardening?

MONTY DON I began gardening at the age of about seven, as part of the household chores rather than as a creative exercise in introducing a child to botany or horticulture. But, by the time I was 17 I had been gardening for about 10 years, almost without knowing that this is what I had been doing. I would come home from school and do half an hour’s gardening each day. I understood the rhythms of the garden. I remember on one spring day, when I was working the warm soil and sowing carrots, having a feeling of ecstatic nowness – a sense of being entirely where I wanted to be, and aware of an absence of desire, because I already had everything I wanted. It was that combination of handling the soil, growing something, and doing something that I knew how to do that made for a very profound experience. That night, I dreamt that my fingers grew as roots into the ground. I woke the next day with a deep sense of wellbeing. Thereafter, I have always gone to the garden for everything I want – a sense of wellness, peace and stimulation. There is practically nothing I would rather do.

SG Since then, you have built up a career as a gardener, both on television and with your books. Aside from the ever-popular Gardeners’ World, you recently did a TV series on French gardens, which included an episode called ‘The Artistic Garden’, featuring Paul Cézanne and Claude Monet. Have artists been a part of your journey as a gardener over the years?

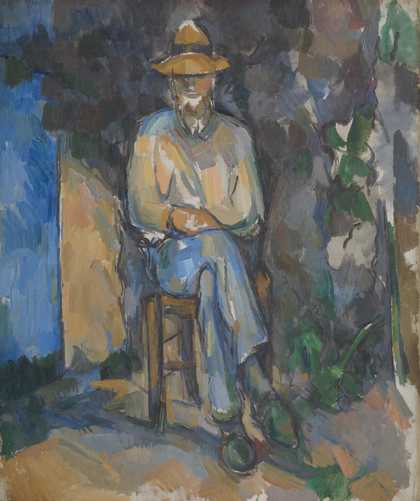

MD Yes, absolutely. Cézanne was incredibly important to me and he was one of the artists whose work I adored when growing up. I painted and drew all the time from a young age – I did O and A Level Art – and used to paint mainly in oils but also with acrylic and watercolours. My grandfather took my brothers and sisters and me to a different London art gallery each school holidays, so I got into the habit of going to galleries at a young age and in my teens particularly fell in love with the post-impressionists. I travelled to the South of France to see for myself the light in which Cézanne had painted. I spent eight months in Aix-en-Provence, living and working in a little village called Le Tholonet. While there, I would climb Montagne Sainte-Victoire, the mountain he had painted so often. At that time, the whole idea of breathing the air that he had breathed was really important and profound to me. I revere Cézanne even more now than I did then. He is one of the truly great masters.

Paul Cezanne

The Gardener Vallier (c.1906)

Tate

SG Cézanne painted the landscape of the area in which he lived, while Monet stayed closer to home, painting the garden he created in Giverny. How did they approach their local environments differently?

MD Cézanne was all about the light and shapes of the landscape of Provence, whereas Giverny was established quite specifically as a garden for Monet to paint. There is certainly a lot to admire at Giverny – there are the fabulous collections of irises for example. Being there at 5am on a May morning to see all the flowers in bloom is an extraordinary thing, and a great privilege, but Monet was no gardener. For example, his pond is, horticulturally, not very interesting. I have been to Giverny about six times, but the more I go, the less I like it as a garden. The right attitude to take, however, is that this was a garden he made for himself, exactly as he wanted it. We know from his letters that he specified exactly the shade of petal he desired, and would get people to hunt for seeds. As such, he was a plantsman and a very good one. But it was all about how he could use them in his paintings. There is a difference between gardens as art and gardens for art. I think the latter are completely subjective, and the problem with somewhere like Giverny, with its hordes of people pouring in, is the inevitable hagiography that goes on, because we recognise there the scenes from his pictures. What we have to ask ourselves is: if there were no paintings, would we visit this garden? It’s not terribly meaningful, because it’s Monet that we are really interested in: we want to see the cup that he drank his coffee from, and to stand on the bridge that he painted.

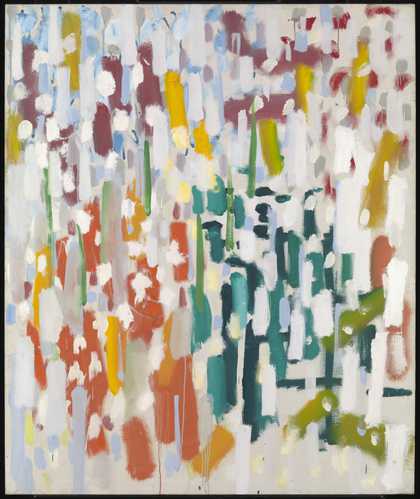

Patrick Heron

Azalea Garden : May 1956 (1956)

Tate

SG Closer to home, there were a number of artists who were interested in plants or who took inspiration from their gardens, such as Cedric Morris at Benton End in Suffolk, Patrick Heron at Eagles Nest in Cornwall, and Ivon Hitchens at Greenleaves in West Sussex.

MD Well, it’s different with someone like Hitchens, who is a painter I love. He endlessly painted his garden, which was filled with poppies, sunflowers and dahlias, as well as the surrounding acres of silver birch, rhododendrons and bracken. I imagine it wasn’t the most remarkable garden (I’ve not been there), but with Hitchens you get a sense of internal illumination, which comes from his relationship with whatever he was painting. The same could be said of some of Samuel Palmer and Stanley Spencer’s pictures too. In these cases, it doesn’t matter what the settings are like as gardens – it’s all about the art. Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage at Dungeness, on the other hand, is a very good example of a garden as art. It works because Jarman responded exquisitely to the landscape around the garden. (The identical garden in a Cotswold village would not work in the same way). Jarman took an unlikely setting for a garden and made something really extraordinary out of it.

SG You might say that about your own garden, Longmeadow in Herefordshire, where Gardeners’ World is filmed...

MD Well, that garden works because it was designed from scratch as a domestic garden that related to its setting – a modest Tudor hall house, which became a farmhouse set in the countryside. From the start, we were clear that we didn’t want to have lawns to play on: no-one was going to kick a football in our garden, even though we had three small children, but there were lots of other things they could do. We wanted to grow lots of vegetables and fruit, and we wanted to play with colour everywhere. But there are lots of things we didn’t do, and if I was to do it now, I would do it differently.

Stanley Spencer

Laburnum 1936

© The estate of Stanley Spencer / Bridgeman Images

SG There is a belief that great art can emerge out of difficult times. The current situation is making people think more closely about the people around them, hopefully in a way that will lead to better community relations. Do you think that the idea of community garden projects can work?

MD Personally, I think community gardens work best when they focus on the people that use them and fulfil a particular need – whether that is company, a skill or kindness. In those cases, they can work really well, but the scope should be limited and essentially modest. So, for example, I was involved in a community garden project in Herefordshire for drug addicts, and that was very specifically about growing food. And there are marvellous gardens that do things for people with Parkinson’s disease, for depression, or for people with learning difficulties. The ones that work least well are the catch-all ones for ‘the community’ – with the idea that somehow these are good, because they intend to do good. But more often they’re not. Community gardens are really complicated, because they’re so loaded with good intentions, which are, in themselves, complicated. Good intentions don’t make good horticulture, but a gardening scheme with a clear purpose behind it can be beneficial.

SG Do you think that gardens and gardening, whether done as part of a community or individually, can help with mental health and wellbeing?

MD Yes, they do help hugely. All the evidence so far is that they help enormously with soothing anxiety and depression. I suspect that this is because you are engaging with the rhythms of the Earth and its seasons, which are much bigger than you, but which you can very quickly and easily be part of. Personally, I would say that the physical connection with the earth, and the contract you make between the process of planting a seed and its growth, really does have a significance. The fact that you get to see the weather change, the light change and the seasons change... and the fact that you did, you planted and you are part of it and will see that change, is hugely empowering and enriching. We all know that looking after something – anything – is very beneficial. And a garden is something that can be looked after in ways both subtle and dramatic. The range and the depth of care is almost infinite. There is lots of evidence to suggest that gardening helps mental health. I get masses of correspondence about this, and have done for years – about grief, loneliness, depression. But there is actually very little research on why gardening helps with mental health. However, there is a big project that is currently being set up at Oxford University aimed at doing just that – on the basis that if you can figure out how gardening helps, you can then prescribe it properly. There is actually a lot of good discussion about getting doctors to prescribe gardening. There is a huge amount of work to be done, of which gardening could be an important part.

SG What is a garden to you? Is there a word that sums it up?

MD No. There is no single word. When travelling around the world, I have always asked people what their idea of a garden is. The best response I ever heard was from the Chilean garden designer Juan Grimm, who said: ‘A clearing in a wood is a glade, and a circular clearing in a wood is a garden’. So, it’s about that relationship between controlling nature, but also having to work with it – that’s the line you walk. A railway siding is not a garden, but it is a very good place for wildlife, whereas a wildlife garden is probably not as suitable for wildlife as a railway siding, but it is a garden. It’s the relationship between shaping and deliberately triggering a garden, and what happens in that garden without you: you are not doing the growing, you are not the weather, you are not the birds that nest in the hedgerow. It is this combination that I find endlessly intoxicating.

Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage was recently saved for the nation. The artist’s archives from the cottage will be placed on long-term loan to Tate Archive, where they will be made publicly available for the first time.

Monty Don is a garden writer and broadcaster living in Herefordshire. He was talking to Simon Grant, Editor of Tate Etc.