Michael McMillan’s installation The Front Room at Tate Britain, 2021.

© Michael McMillan. Photo © Tate (Jaiwana Monaghan) 2021

MICHAEL MCMILLAN My parents are both from St Vincent in the Caribbean and I was born here, so I grew up Black in the UK during the 1970s. The front room was the place where the family showed off who they wanted to be to the world, as a public space in the private home. It was a space that I almost rebelled against, because I felt it didn’t really reflect what it meant to be Black living in Britain – the sus laws, the racism on the streets. It was my mother’s room, and I was a bit ambivalent about it – I thought it was really kitsch. But later I began to realise it was part of who I am, and saw how important that was, because that room was a place of refuge for us. A space where you could at least feel safe, in the Black home, in the front room. I’m curious to know your responses to it. Dennis, we’re of a similar generation…

Neil Kenlock

Young Jamaican Lady Standing in her Mother’s Front Room in Brixton Hill 1973

Digital C-print on paper

34 × 34 cm

© 2021 Neil Kenlock

DENNIS MORRIS A front room for me was that place of sanctuary within the West Indian family. I remember that it was Sundays when we were allowed to go in there, because we’d come back from church and then our mother and father would escort their friends in. They’d walk in and they’d be like, ‘Mm, I see you got a new sofa, nice.’ One of the most important things in your front room was – for the man, anyway – the radiogram. If you had a Blue Spot (Blaupunkt), you were really happy. For the father, that was the most treasured piece. For the mother, it was the sofa. There would be a coffee table in the middle with the most elaborate plastic flowers – in some ways, they were probably preferred to real flowers. As you said, everything was covered with plastic, so as you sat down, you got that squelch. And then out would come the best china, and the conversation would begin.

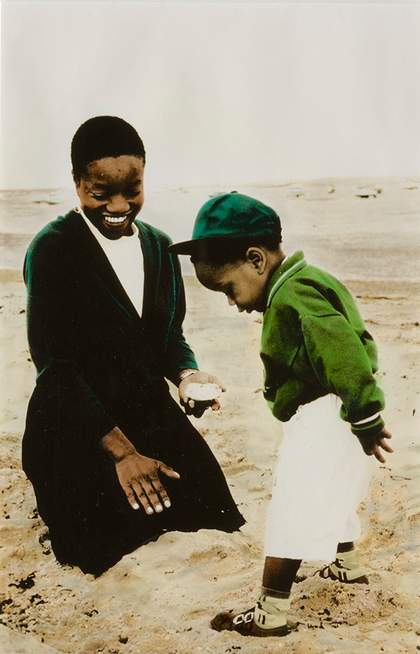

GRACE WALES BONNER Michael, I remember seeing your book, The Front Room: Migrant Aesthetics in the Home, while I was studying at Central Saint Martins and working on my graduate fashion collection. It was an important inspiration, feeling the familiarity of my granny’s home in Stockwell, where my dad now lives and I grew up, and coming to understand these unifying characteristics and materials: the crochet objects you mentioned and the plastic sofa protectors, or the floral carpets, which my granny has in Jamaica as well. To see that there’s actually a lot of common ground in an environment that might feel quite personal made me understand how materials can connect you to the idea of home, or to another landscape; that presence can be transported and reinforce a sense of identity and belonging, and a connection to home.

Photograph from Grace Wales Bonner Spring/ Summer 2015 lookbook

© Wales Bonner. Photo: Dexter Lander

DM One of the surprises for me, growing up, was going to one of my white schoolfriends’ houses, and when I walked in, to my shock, they had exactly the same thing: the plastic over the sofa and the plastic flowers. And I thought, maybe we’re not just on our own out here. I realised, as I grew up, it was really a working-class thing. Everything was preserved in case you had to resell it. One of the tragedies of us, the West Indians, is that we never kept anything – we always threw everything out.

MM These objects are now kind of vintage retro, so people of your generation, Grace, are really fascinated by them and would probably collect them as a sign of returning to a sense of authenticity and connection with the past. There are obviously certain aesthetics associated with the front room. Was there anything in particular that you were inspired by?

GWB I was really interested in the carpets – the floral designs imitating different vegetation. If I think about the grey streets of Stockwell, which is where my family were living, the front room was quite a contrast to that environment. I remember that really standing out.

DM I’ve always felt that Britain at the time of the Windrush generation was a very grey place. And what we brought to Britain was colour, because we came from the Caribbean and were used to vibrant colours. When we came to this cold country, we searched for colours, because we wanted to recreate that environment.

Armet Francis

Fashion Shoot, Brixton Market 1973

C-print on paper

19.1 × 29.2 cm

© Armet Francis. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2021

GWB Even people who hadn’t necessarily grown up in the Caribbean would show their connection to home in how they dressed, and in the materials and colours they chose for the home and to wear. The way that people represent their connections – a sense of belonging through style – is really interesting. But also, the way you integrate different codes, different parts of the wardrobe. A way of wearing clothes that maybe has a lot of layering, or cardigans, as though you’re integrating different elements. I always find this way of imagining putting things together, which feels quite incongruous, is a real expression of style. And for me, it’s also an expression of Black style – this almost improvised way of putting disparate ideas and elements together. It’s like a jazz musician or something, creating something new out of materials.

MM I remember, growing up, my parents talking about African migrants, and they would say, ‘Oh, they’re so colourful.’ They were even more colourful than we were from the Caribbean. So that is the source, in a sense, across the diaspora, of the colour and the layering and the drapery. And this idea of improvising.

DM Because we had to make it up as we went along. In fashion, art, music – improvisation is what we do.

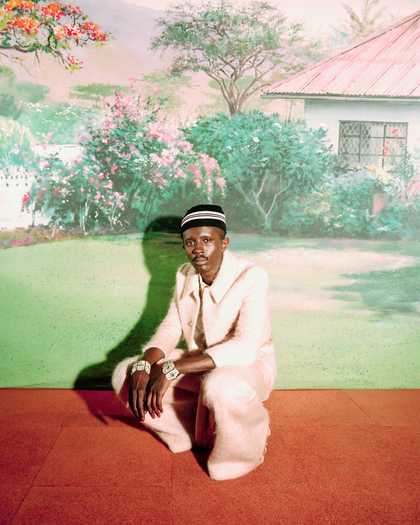

Photograph from Wales Bonner Spring/ Summer 2021 collection

Photo courtesy of Wales Bonner

MM I see in some of your designs, Grace, you bring in everything from Africa to the Caribbean to North America – it’s a kind of mishmash and assemblage of things. As you say, it’s improvised, things that shouldn’t really be together, but you push them together and they work. Do you think that’s also part of being on the outside? Because if you’re kind of marginal, you can do what you want really.

GWB I think in some ways, yes, I feel like I’m allowed to be irreverent. And to play with British codes of dress: what is sartorial or elegant or beautiful, and how can I disrupt that? How can I bring my sense of identity into that, and create something that’s a mix of those things?

I remember looking at photographs by John Goto or Vanley Burke, and seeing how people in Britain were dressed in the 1970s. But then also looking at photographs of people in Jamaica in the 1970s and seeing that they didn’t need to show their identity in such a strong way through their clothes. I also find it very interesting how clothes end up in different places. I remember looking at a photograph of the musician Augustus Pablo in which he’s wearing a very English shirt that looks quite like a Jermyn Street classic shirt, in Jamaica. But it means something else in the way he’s wearing it, with jeans. It’s like he’s giving it a new meaning.

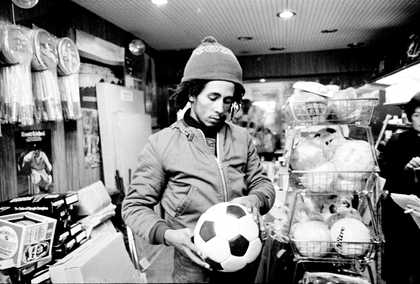

While working with Adidas, I was looking at pictures of Bob Marley wearing tracksuits or trainers. By wearing this performance clothing designed for football in a casual way, he actually created a whole new way of wearing sportswear in Jamaica. I think that’s the ingenuity of Black style; how you can take something out of context and create a whole new style.

Dennis Morris

Bob Marley, Shopping for Trench Town Kids, Leeds 1974

© Dennis Morris

MM Clarks probably never envisaged that their desert boots would be taken to Jamaica and worn in reggae dancehalls, with the sound systems playing artists like Augustus Pablo and Bob Marley. Dennis, one of your classic photos is of Count Shelly Sound System at the Four Aces Club in Dalston in 1973. Black music and sound have also been transformative in the British urban space, and ties in with Black style, of course.

DM Well, the sound system was vital to the West Indian community at the time. At the weekends, families and friends would meet and swap stories about their week at work, and, when they got letters, about what was happening in Jamaica. The people that were running the sound system were like the godfathers of the community. It was also a clever way for a lot of West Indians to be able to pay their mortgages: they kept the basement area of the house empty and held Blues parties there. They’d charge a small fee to come in, and if you were old enough, you’d get the cap of a whisky bottle. If you weren’t old enough, you weren’t allowed into the basement area. You’d stay with your parents, or there was a room where you would play with all the other children. In other rooms were the grandparents as well. Eventually, some plates of curried goat would come in – that was a big moment in the evening, the curried goat. Then, in the later hours, when the kids had gone home, the bad boys would come in. And that’s when the music changed as well – it became quite deep and heavy. That’s also when the heavy smoking started and stuff like that. So there was a rotation of age groups throughout the evening. The sound system was a vital connection between them all. And I think it’s deeply missed within the communities now.

Dennis Morris

Count Shelley Sound System, Dalston 1973

From the series Growing Up Black

Gelatin silver print on paper

50.8 × 61 cm

© Dennis Morris

MM I’m curious, Grace, that you use steel bands in your work, because for me they are carnival – the playing at Mas [carnival] and the Notting Hill Carnival – which is where sound systems also happen.

GWB I’m interested in the idea of processions and the movement of people – even funeral processions and graveside traditions. How things get passed down and how rhythm is so engrained in that passing down. The idea of a procession is, for me, also something that connects Black people in different places all over the world. I’ve been looking at Bob Marley’s funeral, for example – the procession of people there – or at civil rights marches in America, and thinking about the symbolism of people moving and migrating.

I’m also very interested in rhythm and how that can manifest as aesthetics. I’m often drawn to music, but I have a challenge as a designer: how do I translate something rhythmic into clothing? There are West African textiles that have a kind of polyrhythmic metre to how they’re woven, so there are ways of embedding that into a fabric, but it’s kind of an impossible task.

I think that’s also why I’m looking at archival imagery and what people were wearing around these sound systems or in musical contexts. For me, that feels like such a pure reflection of the sound. Seeing how people dressed, how people looked, how people were expressing themselves – there’s so much in that and that’s so valuable. Your photographs, Dennis, are such an important record for my generation, to see where we came from.

Charlie Phillips

Clinton at Cassidy’s Funeral, Kensal Rise 1972

© Charlie Phillips / www.nickyakehurst.com

DM Thank you. I think what Michael and I are doing is laying down a foundation and a blueprint for your generation, and you’re laying down a blueprint for the next generation.

MM Being part of a community where you can connect, and to realise that you’re part of a long tradition, is so important, particularly for younger Black artists emerging now.

John Goto

From the series Lovers' Rock 1977

Micro Piezo print on archival paper

38 × 38 cm

© John Goto. Courtesy of Dominique Fiat Gallery, Paris

DM Grace, how do you find community in your area of work? Because you are a rarity.

GWB I find a lot of comfort knowing that, within the art world and in literature, there are a lot of people that I look up to and admire, and who share a cultural perspective. But in fashion, not so much. Having a specific cultural perspective and representing that through clothing feels quite new within fashion. I had a conversation with the poet Ishmael Reed, and he said clothing is as important to Black culture as drumming. That was an important turning point for me, to realise how important fashion can be. It’s around everything we do, and so integral to who we are.

I know that what I’m doing comes from such a great tradition. There’s a wealth of history of artists that have been working in this ground and quoting foundations – many of them are in this show at Tate Britain. I draw a lot of strength from that community, from seeing their work. I’ve got very clear models of what I’m aspiring to do. There are so many examples in history of Black elegance and Black style and Black intellectualism that I can see and access, so I’m almost just reflecting what’s there. These references are very familiar to me – such as images of a Black man looking incredibly elegant and sophisticated – but in fashion, especially when I was starting, there weren’t so many visible examples. So I’m exposing what I know will probably be quite familiar to a lot of us.

DM Yeah, because we’ve always been there. We’ve always been tapping away and quietly working hard. I remember Peter Tosh saying one of the hardest things in life is to be a Black star. You have to shine so bright to be seen.

Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now, Tate Britain, until 3 April. Curated by David A. Bailey, Artistic Director, International Curators Forum, and Alex Farquharson, Director, Tate Britain. Supported by the Deborah Loeb Brice Foundation, with additional support from the Life Between Islands Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor.

Michael McMillan is a writer, playwright, artist and scholar who lives and works in London.

Dennis Morris is a Jamaican-born photographer who lives in London.

Grace Wales Bonner is a British fashion designer who lives in London, where she is an associate lecturer at Central Saint Martins.