© The Neo Naturists. Courtesy of the artists

To celebrate Women in Revolt! at Tate Britain, we invited nine women to discuss their experiences of making feminist art in 1970s and 1980s Britain, and the social and artistic barriers they fought to overcome.

For Christine and Jennifer Binnie, Wilma Johnson and Lucy Whitman, the shared question was that of how to use images of women’s bodies while, at the same time, insisting on their empowerment. Christine, Jennifer and Wilma went on to use their own skin as a living canvas; for Lucy, known in those days as Lucy Toothpaste, the punk movement proved a fertile, if sometimes problematic, testing ground for political expression. These women were pushing the thresholds of the avant-garde, and yet, as is often the case, these endeavours existed outside of the gallery system.

The Neo Naturists performing punk cabaret at the Fridge, London, c.1980s

© The Neo Naturists. Courtesy the artists

CHRISTINE BINNIE When punk happened, I had just left art college and I was living in a shared house in Eastbourne. We all worked at Birds Eye together, and I used to go to work, put my boiler suit on, and have my hair in a beehive. I remember writing The Jam on the back of our boiler suits, in jam.

LUCY WHITMAN You were definitely a punk!

JENNIFER BINNIE We were just joining in with what we thought punk was. I was more of a country girl – I was into horses. At that time, punk changed fashion almost overnight from floaty, hippy dresses to school uniforms all cut up.

LW That’s why I was excited. It was a change. Before, you could be either a floppy hippy or the girl next door. It’s hard for us to think ourselves back to a time when clothing was so regimented for women and girls. Punk changed that.

WILMA JOHNSON When I was at school, one of my friends started going out with Lemmy from Motörhead, so we were plunged in at the deep end. In terms of music, before punk, there were like three gigs a year, and then suddenly there were 200 gigs a week in London.

CB I think the nice thing about that time was the intimacy. In Eastbourne, where my sister Jen and I grew up, you would go to gigs and know the bands.

LW What attracted me to punk was the fact that it wasn’t just a boys’ club. Because the boys were challenging the status quo, that made it possible for girls to say: ‘What about us?’

I was already a feminist by the time I noticed that punk was going on. My sister Rosalind and I did lots of creative things together, and she drew some wonderful pictures for my fanzine JOLT. She absolutely hated punk, though – it was too loud, too aggressive. But I started going to gigs and reading the NME.

There was the art college connection to punk too. Poly Styrene, for instance, was a visual artist as well as a performer and poet. She made all her own clothes. Except for a minority who went to Vivienne Westwood’s shop and spent a hundred pounds on a pair of bondage trousers, women punks either made their own clothes or bought them from charity shops.

WJ I actually used to wear my great aunt’s old ski clothes.

LW I had a little 1960s jersey suit that had been my granny’s. This whole thing about parody is important in punk…

WJ It was both light and heavy at the same time.

LW And full of contradictions. There were fascists involved, who were serious about it. Then there were people who just thought it was clever to wear a swastika. And then there were hordes of anti-racists. There were sexist punks and there were feminist punks.

CB I didn’t realise until recently that punk was more of a left-wing thing.

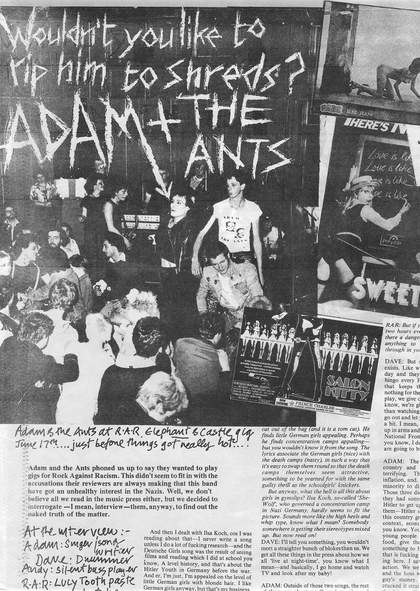

Detail of Lucy Whitman’s interview with Adam Ant, published in Temporary Hoarding #6, August 1978. Designed by Ruth Gregory

Courtesy Lucy Whitman

LW I want to show you some pages from Temporary Hoarding, the Rock Against Racism fanzine. We made them gigantic because they unfolded into posters. We wanted people to read about racism or sexism on their way home from a gig. Adam Ant, who I interviewed for this issue, was keen to do a Rock Against Racism gig, because he could see the dangers of the National Front, but he flirted with Nazi imagery, and he couldn’t see that doing songs about sexy German schoolgirls was a problem. My interview with him got onto the internet a few years ago because I was so hard-hitting towards him.

In the early days of Rock Against Racism lots of bands wanted to play for us, but they weren’t all committed anti-racists – some of them just wanted a gig. And some of them didn’t have a clue about sexism. There was a famous Rock Against Racism gig in Brighton in 1978, with a band called the Fabulous Poodles. They opened their set with a song called ‘Convent Girls’ and the chorus for one of their songs was ‘Tits! Tits! Tits!’ The Brighton feminists were up in arms because it was so appalling. We published their letter in Temporary Hoarding because we wanted our supporters to think about sexism as well as racism.

WJ I went to St Martin’s and I found it patriarchal and sexist. I was making figurative paintings of women, and people would ask why I was painting women. And I thought: ‘That’s weird. It’s okay for men to paint women for thousands of years, but I’m not allowed to paint my own naked body?’ And that was when I met Christine.

CB During that time, I went to Berlin and worked in a peep show and got to know German punks, who walked around in the nude and got tans. It made me feel positive about nudity. Back in London I was working as a life model, and then met artists such as Cerith Wyn Evans and eventually Wilma. I also started going to the Blitz club around that time.

WJ One day I was trying to paint Christine, but my picture wasn’t working. She had to buy some body paint for a performance at the Blitz and I was like: ‘What is this amazing material?’

First of all, I painted Christine with body paint and set up photographs. The pictures themselves were the art, like an extension of my painting. But I decided I wanted to get painted too. One night we went to a New Romantic night club in body paint and it sort of… changed into performing.

CB I was shocked at how shocked people were. I thought that sexual liberation happened in the 1960s and people had wandered around Hyde Park in the nude with flowers painted on them. But I must have got the wrong idea.

WJ The other thing is, there were so many images of nude or semi-nude women everywhere, but they were all airbrushed and very commercial. They were produced by men, for men. So, when people saw our normal bodies, they were shocked.

LW Isn’t this to do with the whole history of art? The naked woman lying on the couch comes to life.

WJ Exactly, and she has agency.

The Neo Naturists (left to right: Christine, Jennifer and Wilma) performing in body paint outside Centre Point, London, 1984

© The Neo Naturists. Courtesy the artists

JB I met Wilma in 1980, and that year I stayed in London with Grayson Perry, who was my boyfriend at the time. Wilma was wearing these incredible Marie Antoinette dresses and I think Grayson started getting a bit braver about going out in public dressed up.

But I started to get a bit bored, because whenever Grayson dressed up as a woman, I wasn’t really his girlfriend anymore. He was like my aunty because he used to dress much older. And then he started being with what we called the ‘gender benders’ we’d met in London, and I felt a bit left out. I started thinking, what can I do that’s going to get more attention? Obviously the next step was to go out naked, wearing only body paint. As one does…

The clubs we went to – Taboo, or the Blitz or the night we would perform at in Heaven – was more like queer culture. ‘Queer’ in those days meant a gay man, but what people mean now is someone who doesn’t quite fit into…

WJ … mainstream sexuality.

JB When I look back, I would say we were all queer at that time.

CB I’ve always felt like I didn’t fit in. I didn’t fit into the Blitz or being a punk. I didn’t fit into being an art student. I suppose that’s because I’m queer.

WJ I think that’s where the Neo Naturists fitted in. The first thing we all did together was at a club called Wedgies in Chelsea.

CB We didn’t really have a plan. We just took some body paint with us and on the way there, we found that piece of orange material in a skip, so we decided to call ourselves The Segments and turn ourselves into an orange.

WJ It went down a storm. Nicholas Parsons and Diana Dors were in the audience, and Jen gave Diana a banana. They were so posh. They all loved us, because I guess they could afford dry cleaning bills.

JB Grayson, and other men, used to do it with us too.

CB It wasn’t always women, that was really important. People would say, ‘Oh, aren’t you brave to do it as women’, but actually, I think if we’d have been men, we’d have been even braver.

JB Well, I think Grayson has mentioned that. He got lighted cigarettes thrown at his willy!

WJ Men didn’t – people didn’t – like to see naked men.

LW Well, women’s bodies are on display all the time.

I have a copy here of the album cover for Cut by The Slits. It was released in 1979, so it probably predates the Neo Naturists. But it was very controversial. I wondered what you thought of it?

CB They were a big inspiration for the Neo Naturists.

JB We sort of wanted to be like The Slits, didn’t we?

LW It was a controversial cover because women were baring their breasts. But then this is a problem, I think, for feminists. How do we use our bodies to destroy patriarchy?

WJ At that time there were a lot of feminists who thought you shouldn’t wear makeup. So, imagine what they thought about us taking our clothes off and painting ourselves gold? It was all mixed up.

CB When I look back at our photos of when we were in our 20s and we thought we had these quite extreme bodies, because we had tummies and…

WJ … we were described as grotesque in the national press.

CB But when you look at them, I’m sure a lot of men thought we were sexy. When the tabloids tried to take pictures of us, they asked us to put knickers on. But the thing is, it’s important to not have your knickers on. Because wearing knickers is sexier in a way than if you’ve got pubic hair. I suppose we took it a step further than The Slits and we realised the titillation of knickers.

LW It’s interesting, there was this burgeoning of women’s punk and post-punk bands late 1970s, early 1980s. And then they all disappeared. Viv Albertine from The Slits became a film director. Lesley Woods from Au Pairs became a barrister. My personal feeling is that they were too intelligent and had too much self-respect to want to stay in the music business. If you think about Harvey Weinstein, that was probably going on in the music business too.

Back then, nobody took us seriously. We were the hairy-legged feminists. But everything we fought for is now mainstream discourse. The same thing has happened about racism. Now, we actually get a report which says the police are institutionally racist and misogynist. Black people were saying the police were racist 40 years ago!

CB We’re still the same people – we just happen to be 40 years older. As far as taking our clothes off, it’s not only that we are women, but we’re older women. That is an added layer as to why we’re still here. I remember saying in an interview in the 1980s, I’m going to be a Neo Naturist octogenarian. And I think I am, touch wood and whistle for luck!

I’m not looking forward to getting loads of wrinkles, but I am looking forward to getting painted when I have a wrinkly body and getting all the body paint in…

JB We’re going to need more body paint.

LW We were all, in our own way, pushing against patriarchy when we had our young bodies, but we’re still doing it now.

JB I think we’re more powerful now we’re older.

LW That’s why I’m interested that students come to me and say: ‘What

was Rock Against Racism? What was Rock Against Sexism?’ I was a teacher for a long time in further education, and I think I am still a teacher at heart. I want to share what we discovered, what we created, with the next generation.

Christine Binnie is an artist who makes contradictory, folksy ceramics and happenings.

Jennifer Binnie is a painter, living in and inspired by the natural and spiritual worlds.

Wilma Johnson is a painter, photographer, performance artist, writer and traveller celebrating the female gaze.

Lucy Whitman is a writer currently writing about dementia. She created JOLT fanzine, and wrote for Rock Against Racism, Rock Against Sexism and Spare Rib.

They talked to Figgy Guyver, Assistant Editor of Tate Etc.